By Patrick Gillespie and Jonathan Gilbert

Argentina’s record drought is worsening inflation and driving the peso to new lows, undermining the ruling party ahead of October’s presidential elections.

This could represent a dramatic change in the country’s political direction.

The International Monetary Fund cut its growth outlook for South America’s second-largest economy on Tuesday (11), as analysts warn that drought will cause a deep recession.

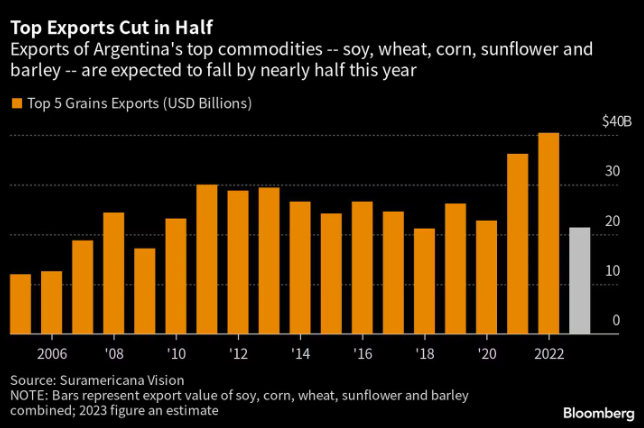

Millions of hectares of corn, wheat, and soybeans – Argentina’s biggest exports and a major generator of jobs and tax revenue – will be ruined this year, sabotaging about US$19 billion in inflows, according to one estimate.

The drought is worsening an already untenable economic situation.

With rapid money printing, internal political conflicts, and the government’s inability to control deficits, annual inflation has surpassed 100%.

The peso has lost two-thirds of its value since the onset of the Covid pandemic, even with a myriad of exchange controls.

The ruined crops will likely cause economic effects far beyond Argentina – from countries where pigs eat more soybeans from Argentina than from any other country to the grain trading markets of Chicago.

In Argentina, the resulting dollar shortage will likely limit imports for manufacturers, require new currency controls, and further fuel inflation through higher food prices.

Meat prices, for example, jumped more than 30% in February from the previous month.

The country’s foreign debt is traded at around 25 cents on the dollar.

Calamity has fueled predictions of political strife.

An outsider candidate, Javier Milei, leads the polls as voters grow frustrated with the established parties, especially the ruling Peronist coalition, ahead of the presidential elections.

Vice President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, the country’s two-time president, and her longtime conservative rival, Mauricio Macri, have said they will not run.

The current president, Alberto Fernández, has not stated whether he will seek re-election but will likely be defeated if he does.

The Fernández government has responded to the ongoing economic disaster with desperate maneuvers to avoid implosion, including forced bond swaps and the creation of several exchange rates.

Analysts warn that the strategy is storing up problems for the future, increasing the risk of a massive currency devaluation that would fuel inflation and worsen poverty even faster.

“You are not postponing a problem,” said Alberto Ramos, economist for Latin America at Goldman Sachs (GS).

“You are playing with fire. It’s very dangerous.”

Argentina’s Economy Minister declined to comment.

Ariel Striglio knows the drought of the 700 hectares of soybeans he leases near Chabas, northwest of Buenos Aires.

He expects to grow 4.5 tonnes of soybeans per hectare in a normal year, but this month’s harvest will yield less than half that.

With the drastic reduction in income, it will be difficult to pay off his bank loan and landlord.

“I have never experienced such an extreme drought,” said Striglio, 57, who has been a farmer for 25 years. I end up deeply in debt.”

Striglio is right: the moment in Argentina – the world’s largest soybean meal and oil exporter is unprecedented.

Fernández told US President Joe Biden at the White House on March 29 that this is the worst drought in Argentina since official records began in 1929.

The Buenos Aires Grain Exchange said this year’s soybean harvest of 25 million tonnes will be the worst ever recorded.

At the start of the season, soybean fields had the potential to produce 48 million tonnes.

The scope of destruction is grim in the vast plains known as the Pampas, a fertile expanse of 777,000 square kilometers stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to the semi-arid plains of the west.

Local media have shown images of decomposing cattle corpses after they died of dehydration earlier this year.

Irrigation canals are dry, ponds are empty, and fields are completely devoid of vegetation.

While consumer prices soar and the central bank spends to prop up the peso, its easily accessible cash reserves were only US$2.7 billion at the end of March, about US$6 billion less than at the beginning of the year.

Although the central bank’s coffers would normally get a boost from soybean exports at harvest time, the shrinking crop will reduce inflows this year.

This will affect the government’s ability to repay its $44 billion debt to the IMF.

On Tuesday (11), the fund cut its 2023 growth forecast for Argentina to 0.2% from 2% previously.

Economists in Buenos Aires expect the economy to shrink by about 4%.

“The economic situation has become more challenging since the beginning of this year due to the increasingly severe drought and policy setbacks,” Gita Gopinath, the IMF’s First Deputy Managing Director, said in an April 1 statement.

Tighter monetary policy with modifications “may be necessary to safeguard macroeconomic stability.”

Economy Minister Sergio Massa is turning to elaborate and complex measures to prevent a collapse of the peso, including several temporary exchange rates.

For now, soybean exporters can sell their product at 300 pesos per dollar, much better than the official rate of 211 per dollar set by exchange controls.

Better conditions should encourage more exports.

On the debt side, Massa said he would force state-owned companies to sell their dollar-denominated bonds for pesos.

This move would give the government some short-term power to curb volatility in Argentina’s exchange rates.

Massa also swapped $4.3 trillion (US$21.7 billion) of maturing debt to give the government more breathing room by forcing Argentina’s state-owned companies to participate.

The involuntary nature of the swap caused S&P Global Ratings to declare Argentina in default on its local debt.

The minister also pegged the interest rates on the bonds to inflation, likely deferring the debt.

This could be the burden of one of the candidates before the elections.

Milei, who calls himself a libertarian, leads the polls with anger-filled rhetoric, including a plan to exchange the peso for the US dollar as Argentina’s official currency.

Patricia Bullrich, the most conservative candidate in the opposition coalition, delivers a pro-business and tough-on-crime message.

Augusto McCarthy, a farmer, is considering voting for Milei or Bullrich.

He wants to see the next government fix structural problems, such as high public spending, and help farmers.

Until then, McCarthy, 39, must deal with the consequences of the drought.

He sold about 200 of his 800 head of cattle this year because there was not enough grass to feed them.

Some of his soybean crop is in such bad condition that he won’t even harvest them. Instead, he is letting the cattle roam the fields to eat what is left of the wilted plants.

“A lot of farmers are not going to be able to survive after this drought,” McCarthy said.

“You can’t see water anywhere.”

With information from Bloomberg