(Opinion) At first glance, Guillermo Lasso in Ecuador, Pedro Castillo in Peru, and Luis Arce in Bolivia – the three Andean heads of state – could hardly be more different.

Lasso is an elite liberal-conservative banker, Castillo a Marxist and political neophyte, and Arce a technocrat at the head of a left-wing populist mass movement.

But the three also have much in common.

They all came to power during the pandemic in countries heavily affected by COVID-19.

And all three are struggling with the consequences today: disrupted supply chains, inflation, unemployment, and impoverishment.

And in the wake of the economic crisis, another of the region’s old ills has returned: political instability.

Voters struggling with social decline have little patience with politicians.

In April 2020, when little was known about COVID-19, the Ecuadorian port city of Guayaquil was hit as hard and at about the same time as Italy.

The health care system collapsed, the dead were laid out on park benches for days, and morticians had to make do with cardboard coffins.

Similar dramatic scenes played out in Peru.

There was no oxygen, the relevant hospital facilities were in ruins, and the dominant companies were speculating on prices.

Bolivia’s right-wing government was completely overwhelmed.

Hospitals were in chaos, regions were left to fend for themselves, and corruption flourished in procuring masks and ventilators.

In all three countries, there were holes in the social safety nets and greedy politicians who not only encouraged the situation but also sought to profit from it personally.

Arce, Lasso, and Castillo wanted to respond to this debacle.

Arce, the crown prince of Evo Morales’ leftist Al Socialismo (MAS) movement and father of Bolivia’s economic miracle, clearly won the October 2020 presidential election.

Lasso, a banker who was elected president in May 2021 in his third presidential bid, won mainly on nostalgia: voters expected a quick return to stability and economic growth.

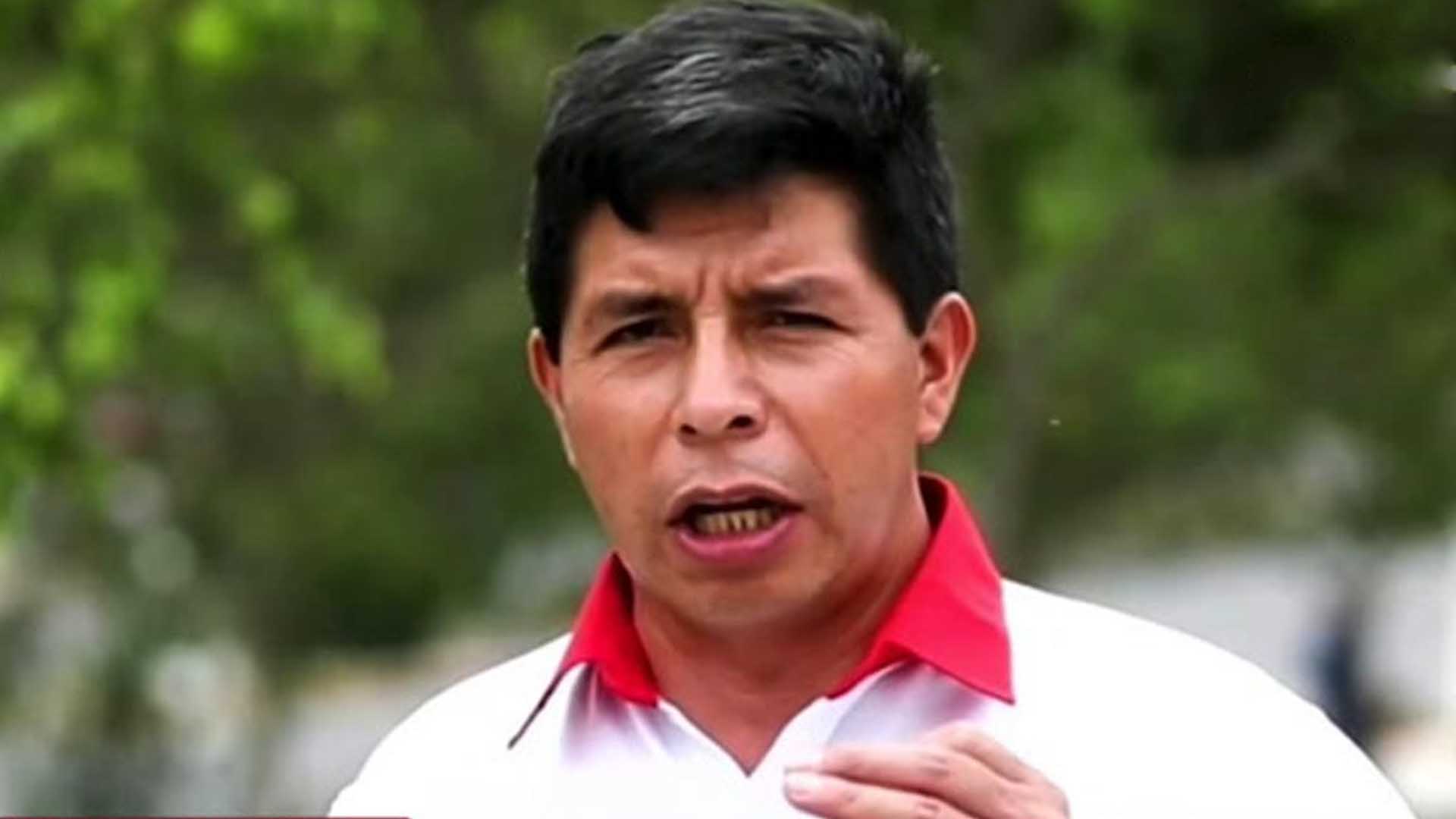

By contrast, Marxist rural schoolteacher Pedro Castillo, who won Peru’s July 2021 election, embodies the opposite: a shift away from the neoliberal consensus and hopes for more social policies.

Castillo is the traditional outsider who came to power on a wave of protests and fears that his opponent, the dictator’s daughter Keiko Fujimori, would win the second round.

But none of them has found happiness. Their countries continue to lurch from crisis to crisis.

Lasso tried to revive the Ecuadorian economy with neoliberal austerity measures, which crippled it while inflation rose.

This triggered a major wave of protests, led by the indigenous confederation CONAIE, which had already cornered many presidents.

The protesters succeeded in wringing a compromise from Lasso that not only maintains gasoline subsidies but also imposes price controls and a moratorium on new mining and oil projects.

Lasso is now in a double bind, as the export of raw materials – along with cut flowers and bananas – is one of the country’s main economic pillars.

Lasso could only extricate itself from this predicament thanks to rescheduling its national debt with China.

Two-thirds of Ecuadorians rate Lasso’s performance negatively.

His recent telephone conversation with his predecessor and nemesis, left-wing populist Rafael Correa, only reinforces the impression that Lasso is finished.

As for Castillo, he has been in office for 14 months and has done virtually nothing. His government merely lurches from one scandal to the next.

Seventy-two ministers have changed. With the help of alliances of convenience, he has been able to avert two impeachment proceedings.

However, the attorney general has opened six investigations against Castillo and his family, three of them related to public service contracts.

One of his daughters is in prison, and a nephew is on the run.

Peru’s 130-member Congress is divided among 15 parties. Many deputies blackmail the government into giving them personal concessions, such as relaxing controls on transportation companies and private universities.

Meanwhile, 70 percent of Peruvians struggle to survive in the informal economy, where legal and illegal activities mix in unrecognizable ways.

Meanwhile, a power struggle has erupted in Bolivia between Arce, his vice president, David Choquehuanca, and his predecessor, Morales.

All three want to run as MAS candidates in the 2025 presidential elections and throw mud around like mad.

A MAS representative from Morales’ wing revealed that Arce’s sons had accepted bribes for the award of lithium deposits in the Uyuni salt flats to a U.S. company.

And a journalist revealed that Arce had given his sons important posts in the national energy company and appeared to be personally benefiting from the state biodiesel plant under construction.

In response, a MAS representative from Arce’s ranks countered that Morales was having his campaign financed by Argentine and Brazilian drug traffickers, whereupon Arce demanded the resignation of two ministers for serving imperialist interests.

Choquehuanca hopes to profit from their dispute.

The native intellectual likes to point to the need for a generational change and can rely on the reform-minded wing of the MAS’s young cadre.

But the party is at odds with itself and could even disintegrate, especially if election officials follow Arce’s instructions and end all forms of illegal campaign financing and vote buying.

CRIME FLOURISHES

Weak governments benefit from organized crime the most. During the pandemic, Ecuador’s drug mafia greatly expanded its presence in border regions with Colombia.

Since February 2021, more than 400 inmates have been killed in prison riots, and hitmen have murdered three prosecutors.

The murder rate doubled to 14 per 100,000 population in 2021 compared to 2020.

The state of emergency has not prevented criminals from detonating explosive devices that have injured scores of people.

Drug gangs are struggling primarily to control smuggling routes around the northern port city of Guayaquil.

According to police, drug seizures rose from 79 tons of cocaine in 2019 to 170 tons in 2021.

The cartels are taking advantage of Ecuador’s fractured social fabric to recruit new people, and Lasso’s austerity policies exacerbate the trend.

Another epicenter of crime is in the Amazon lowlands, where thousands of illegal gold miners have set up shop on riverbanks since 2021.

Mercury and sediments are causing the collapse of ecosystems of important rivers like the Napo.

Dubious middlemen have laundered profits from this gold, further growing Peru’s illegal economy, which has been comparatively weak.

Peru is a cautionary tale of where this is leading. There has long been a symbiotic relationship between organized crime and local and regional politicians in some areas.

Gold diggers, drug traffickers, and money launderers who become governors and mayors by buying votes are no longer uncommon.

In local and regional elections in early October, more than 600 candidates with pending criminal cases ran for office, of whom 17 were elected, according to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime.

This has been part of Peruvian political life for more than a decade, with no measures taken to prevent it and no shock to the population.

Nevertheless, the regions account for two-thirds of government spending and serve as stepping stones to careers in national politics.

There are also various types of criminal lobbies in Peru’s Congress.

One congressman covered up for a construction cartel, while others promoted corrupt judges and sold acquittals as indulgences.

Currently, 68 deputies are under investigation, most of them belonging to the Alianza para el Progreso party of former strongman César Acuña, who became rich overnight with a consortium of public schools across the country.

But Peruvian imitators of legendary Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar are not content to sit in Congress like him, says drug expert Jaime Antezana.

According to him, even narco-candidates have been running for the presidency since 2016.

In Bolivia, the economic crisis is also increasingly blurring the lines between politicians and the mafia.

The pandemic is one reason for this; another is the massive expansion of the state apparatus at the expense of the private sector.

This means that the Bolivian budget is strained, while the national debt is rising.

MAS finds some relief in illegal alliances of convenience, in part through land grabs that encourage coca growers and settlers in the highlands to occupy land in the lowlands.

Illegal and armed occupations do not primarily target private property: it is primarily indigenous lands and protected areas in the Amazon where authorities often turn a blind eye.

Most land grabbers are MAS land speculators who clear the forests and then sell the land for profit to mining companies or agribusiness.

This benefits the government in three ways: opening up new areas boosts the economy, its supporters are supplied, and the opposition is weakened as the new settlers displace most of the lowlands, the traditional fiefdom of the conservative parties.

In the Andes, coca cultivation has increased since 2020.

Peru’s altiplano currently grows 80,000 hectares of coca – the raw material for cocaine production – compared to 30,000 hectares in Bolivia.

The area under coca cultivation in Ecuador remains comparatively small, at less than 1,000 hectares.

But its proximity to Colombia’s large coca fields makes northern Ecuador an important center for cocaine production and export.

With weakening economies and overburdened government budgets, these three countries cannot keep up with important policing and prosecution of illegal activities.

While the drug trade may be welcome by some of their governments, it is a major risk.

The danger of ungovernable narco-states in the Andes is growing.