By Ryan McMaken, Mises Institute

RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Some US policymakers and pundits are declaring that Russia—and its population—are cut off from the rest of the world. For example, political scientist Nina Khrushcheva has said, “The rest of the world” hates Russia and “Russia is the global enemy.” The New York Times concludes Russia is now “an economic pariah” and that a “new iron curtain” is falling.

Undoubtedly, the sanctions imposed by wealthy Western nations will negatively impact the Russian regime, the Russian economy, and the Russian people. Ordinary Russians, who currently enjoy a GDP (gross domestic product) per capita that is only a fraction of the size of that of many Western countries, will suffer greatly.

But when it comes to the degree of Russia’s isolation, those gloating about Russia being “cut off” are overstating the case. In fact, many of the world’s largest countries have shown a reluctance to participate in the US’s sanction schemes and have instead embraced a far more measured approach.

Read also: Check out our coverage on curated alternative narratives

So long as China, India, Brazil, and other large states continue to be at least partially sympathetic toward Moscow, they will provide a large market for Russia’s natural resources and its other exports. And these nations have signaled they’re not cutting off Russia just yet.

Moreover, if the US is going to demand that the world falls into line with US sanctions, that means the US will have to enforce its policy on reluctant nations. That ultimately means the US will need to threaten—or in some cases, implement—secondary sanctions designed to punish countries that don’t sanction Russia as well.

The long-term effects of constructing a coerced global anti-Russia bloc may prove costly for Washington. In any case, pronouncements of a new iron curtain falling around Russia appear premature.

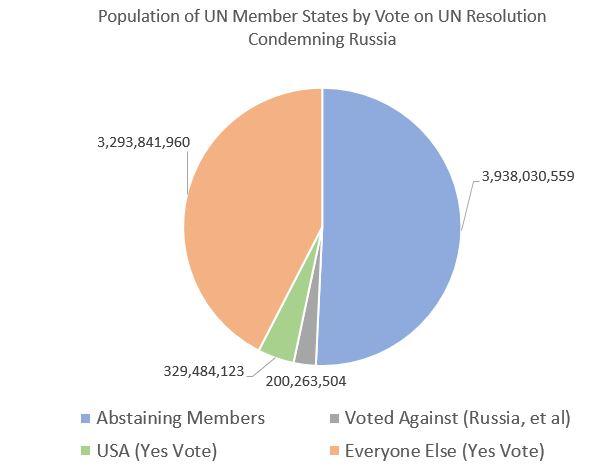

Thirty-Five UN Member States—Representing Half the World’s Population—Abstained

For Americans watching TV news, it undoubtedly sounds like the entire world has united behind an American-led campaign of moral righteousness against the Russians. However, in much of the real world, things look a little different. Anthony Faiola and Lesley Wroughton summed up the situation in the Washington Post a couple of days ago:

“Many countries in the developing world, including some of Russia’s closest allies, are unsettled by Putin’s breach of Ukrainian sovereignty. Yet the giants of the Global South—including India, Brazil, and South Africa—are hedging their bets while China still publicly backs Putin. Even NATO-member Turkey is acting coy, moving to shut off the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits to all warships, not just the Russians.”

“Just as Western onlookers often shrug at far-flung conflicts in the Middle East and Africa, some citizens in emerging economies are gazing at Ukraine and seeing themselves without a dog in this fight—and with compelling national interests for not alienating Russia.

In a broad swath of the developing world, the Kremlin’s talking points are filtering into mainstream news and social media. But even more measured assessments portray Ukraine as not the battle royal between good and evil being witnessed by the West, but a Machiavellian tug of war between Washington and Moscow.”

Meanwhile, James Pindell at the Boston Globe concludes,

“Possibly lost in all the headlines [about the whole world being united against Russia] is that it is not the entire world against Russia. In fact, most of three huge continents—Asia, Africa, and South America—are either still working with Russia or trying to project the image of neutrality.”

“It easy to see why so many come to the wrong conclusions. Many of those crowing about a world united against Russia are often extrapolating from the fact that most of the world’s regimes voted for a recent United Nations resolution condemning the Russian invasion of Ukraine.”

Indeed, 141 UN member states voted earlier this month to condemn Russia for the invasion. Only five states, including Russia, voted against the measure. It is assumed that virtually all the world has condemned Russia and is also enthusiastic about the US’s sanctions.

Yet, thirty-five states did choose to abstain from the vote condemning Russia, and many of these abstaining states are huge states indeed—they’re those large states from the Global South mentioned by Faiola and Wroughton.

In fact, the states that either abstained in the UN vote or voted against it contain more than half— 53% —of the world’s population. Among the abstaining states are China and thirty-three other states that combined have up to more than 3.9 billion of the world’s 7.7 billion people. Combining the no voters with the abstaining states adds another two hundred million plus people to the bloc of states refusing to condemn the Ukraine invasion.

Many former Soviet states are in the bloc not voting to condemn Russia, as are all the large states of South Asia—Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh. Africa also appears to fit into the region that apparently concludes it has ” no dog in this fight as well.”

Nearly one-third of Africa’s regimes—sixteen states—abstained in the UN vote. Iraq—a country that the United States spent twenty years and trillions of dollars trying (unsuccessfully) to turn into a US client state—voted to abstain as well.

Of course, how a regime votes in the UN General Assembly doesn’t tell us much about the man’s opinions on the street in each country. But it should be noted that—as shocking as this may seem to Americans—billions of people in the world don’t automatically agree with whatever the US government says about who the world is supposed to hate at any given time.

In any case, the man on the street doesn’t make policy. Suppose one-third of the regimes in Africa, most of South Asia, plus China and Vietnam are now refusing even to condemn the invasion of Ukraine. In that case, that doesn’t exactly speak to a world that is lining up to obey US-led sanctions and “isolate” Russia.

Admittedly, looking at population will overstate the geopolitical clout of these dissenters, and population gives us a limited view of the size of the economies of these states. This considered, we nonetheless find that the economic bloc of abstainers is not exactly negligible. Moreover, even among countries that voted with the US on the UN resolution, there has been a lack of enthusiasm for American-led sanctions.

Both Mexico and Brazil, for example, voted for the UN resolution but have also signaled they are not interested in imposing harsh sanctions on Russia. Mexico’s president has flat-out stated he has no intention of following the US’s lead on sanctions.

Argentina’s regime is resisting sanctions and has stated it believes sanctions to be contrary to the peace process. Brazil, Chile, Uruguay, and other Latin American states are trying to punch holes in the US’s sanction demands.

When it comes to Africa, Pindell notes:

“Across the ocean, no country in Africa, including South Africa, has joined in the call to make Russia an outlier in global relations. Some of this has to do with Russian military ties to certain nations or that some African nations don’t feel the need to wade into European relations after centuries of European imperialism and colonization.”

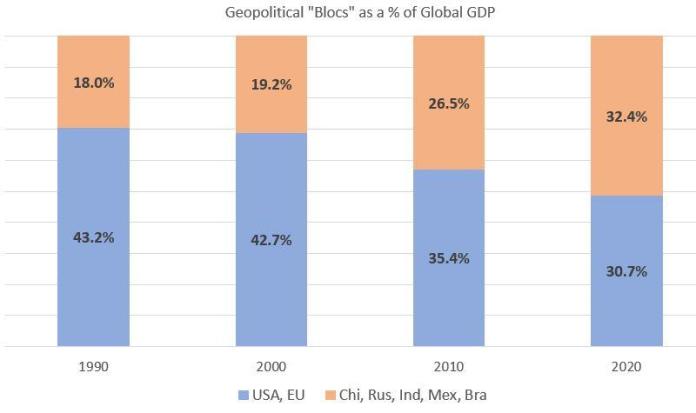

So, what chunk of the global economy is likely to maintain ties with Moscow during this supposed isolation period? Looking at a limited sampling of sanctions resisters—i.e., Russia, India, China, Brazil, and Mexico—we find this “bloc” combined makes up a full third of global GDP (China and India, of course, make up most of this). That’s similar to the combined economies of the US and the EU.

Once upon a time, of course, being cut off from the US and Europe would have left any pariah with only a tiny sliver of the global marketplace. Back in 1990, for example, the US and the EU combined to make up more than 40 percent of the global economy while China, India, Mexico, Russia, and Brazil all combined for a measly 18 percent.

But things have changed over the past thirty years, and the two blocs are now equal:

To use an old Cold War term, all this leaves a third of the global economy “nonaligned.” As we’ve seen, much of Africa, Asia, and even Latin America remains unconvinced that they need to be cutting off trade with Russia.

We could get even more conservative in measuring economic strength outside the US-EU bloc. No look at geopolitical, economic clout is complete without considering the role of total wealth.

And this is where the US and its closest allies look most potent. After all, according to Credit Suisse, 30% of the world’s wealth is American wealth, with Chinese wealth coming in at about 18% of global wealth. Western European wealth is immense as well, with the UK, France, Italy, Spain, and Germany coming in at a combined total of 16%. So, yes, the China-India-Russia bloc makes up only one-fifth of global wealth, while the US and Western Europe combined hold nearly half of global wealth.

But that also leaves nearly half of the world’s wealth in places that can’t exactly be taken for granted as far as US sanctions are concerned.

How the US Could End Up Isolating Itself

Now, the big question is how Washington will respond to other countries that refuse to jump on the sanctions bandwagon. If the US decides to be content with “sending a message” with sanctions and leaving it at that, then the US will have little to worry about in terms of maintaining good relations with trade partners and geopolitical partners.

Even relations with China would continue largely as normal. But it is becoming clear that most of the world’s regimes don’t plan on voluntarily casting Russia into the outer darkness. If the US wants to isolate Russia truly, Washington will have to threaten and coerce other regimes that aren’t going along with it.

The US then puts itself in the position of spending valuable geopolitical capital to coerce potential partners like India, Pakistan, and Mexico into toeing the line on sanctions. It remains to be seen how far the US is willing to go. If it goes all-in on this, it will damage relations with allies, which could limit the US’s geopolitical position. That, of course, is exactly what Moscow and Beijing would love to see.

Ryan McMaken (@ryanmcmaken) is a senior editor at the Mises Institute. Ryan has a bachelor’s degree in economics and a master’s degree in public policy and international relations from the University of Colorado. He was a housing economist for the State of Colorado. He is the author of Commie Cowboys: The Bourgeoisie and the Nation-State in the Western Genre. This article was originally published on the Mises Institute.