RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – (Opinion) South America is unquestionably a state laboratory. So what can we learn about the future of the state? How it fails better – or how it does better? This is the question to address.

The magnitude of the events that swept across Chile on October 18th last year shocked the world. Contrary to the usual global perception, which views this small country in the southern hemisphere as a model nation, massive protests took place under the banner of various social demands (better access to health care, free education, minimum wage and pensions).

Violence surrounding these protests escalated rapidly and led to chaos in all major cities – particularly in the capital Santiago. A government forced into a defensive position had to make a number of concessions, one of which was the referendum on a new Constitution. But the violence continued, resulting in the destruction of infrastructures (in particular subway stations), falling private investment, disappointment and uncertainty within society.

Most importantly, however, questions regarding the role of the state surfaced. It has since become clear that the Chilean state must find a new balance between extended social functions and the current market economy. What is less clear is what role it should play in the future – apart from the fact that the situation is likely to have changed significantly with the outbreak of Covid-19.

False liberalism

As in other parts of Latin America, in Chile the state preceded the nation. Compared to Europe’s historical experience, this is a crucial difference that needs to be explained.

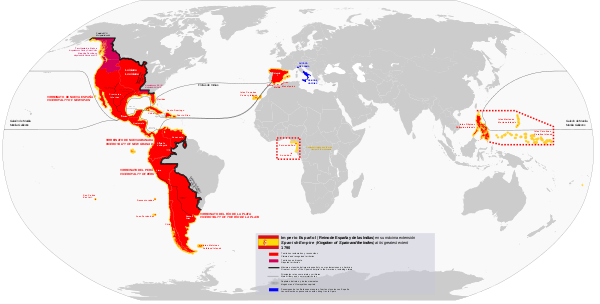

The collapse of the Spanish Empire in the first decades of the 19th century left a fragmented subcontinent with few resources to replace the old colonial administration. Paradoxically, in Spanish America, the reference to liberalism, which after independence was to provide the blueprint for building new nations, led to an enormous expansion of the state apparatus.

One country after another ignored the classical liberal tradition of minimizing the state apparatus, and established a policy of state intervention in all areas of national life. Even in Chile, a rather moderate case by Latin American standards, the education system, infrastructure and social services, including the health system, were developed exclusively under state leadership.

The trend was further reinforced when Chile embarked on a project of industrialization in the 20th century that required massive state resources – including food allowances to keep wages in the industrial sector sufficiently attractive. But the demand for labor, the impact of the Second World War, political polarization, endemic inflation, the massive confiscation of rural properties, and international mining companies led to the 1973 military coup, which was an explicit reaction to a policy of state intervention that seemed to have no end.

The regime of Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990) reversed the trend of growing state influence by massively cutting jobs in the public sector and privatizing most state services (in particular education, health and pensions). Furthermore, Pinochet promoted a neoliberal philosophy that emphasized individualism, competition and the supremacy of market forces.

The 1980 constitution, which is now on the verge of being repealed, preserved these principles and passed them on to the democratically-elected governments that replaced the dictatorship after 1990. The centre-left coalition, which remained in power for over twenty years, had to live with the conditions laid down during the transitional military negotiations. While adhering to the country’s moderate political traditions as a whole, it gradually opened up to reform.

Certain concessions to the military regime were tolerated to enable a return to democracy. In contrast, the economic model was preserved under the pressure of constraints. The favorable global environment helped to achieve stable and sustainable growth of around five percent per year, reducing the population’s poverty rate from almost 50 percent to less than 10 percent.

However, there was also gradual unrest over persistent or growing inequality and corruption, in both the corporate world and the armed forces.

Mistrust of Millennials

In the period after the military dictatorship, a new generation emerged for whom the idea of compromise was alien – the price their parents had paid to achieve the democratic transition. Indications of dissatisfaction were visible in large parts of the population, but they were particularly noticeable among secondary school and university students who no longer trusted the pledges of the political and economic model, which in practice were the only opportunities actually available to them.

Trust in the restored democratic state began to crumble. Thus, October 2019 was not a sudden event: it became evident gradually, as the millennial generation gradually became a majority.

However, this generation’s marked discontent was the least visible aspect of the events that took place late last year. Daily life was marked primarily by a shocking collapse of traditional behavioral conventions and, concurrently, the state’s inability to maintain public order.

For many years citizens had respected the law and embraced its principles. The state now tried to enforce it further, despite facing growing challenges: students and many ordinary people jumped over turnstiles to save on public transport fares; traffic rules such as right of way or stop signs were ignored; traffic lights were destroyed – partly in protest, but also for local practical reasons; sidewalks became a war zone between pedestrians and cyclists, pedestrians and illegally parked cars, and pedestrians with each other.

As the number of accidents and injuries increased, the state retreated. Its reluctance to intervene encouraged further transgressions, turning everyday life into a nightmare unlike anything Chileans had experienced since the extreme polarization after the early 1970s.

The new free mentality

A long time ago Max Weber emphasized how much the state’s legitimacy hinges on its credibility. In much of Latin America, this kind of legitimacy has now vanished. Particularly in Chile, distance from all areas of government has reached virtually unimaginable records.

Approval ratings are in the single-digit percentage range, not only in relation to the President, but also to Congress as well as political parties. Citizens no longer identify with the institutions of a representative democracy: quite the opposite – they despise them.

But what do they want, apart from an extended welfare state to replace what is perceived as a “predatory economic model”? Among the answers to this question are the stress on multiple – and changing – social and individual identities; demands to make personal ideals and expectations the law in the country; and most importantly, the rejection of everything that has become a symbol of the status quo.

The graffiti on the walls of Santiago’s city center shows what this leaderless movement wants: in addition to hostile slogans directed at the police (carabineros), there are calls such as “Everything free”, “Freedom for pets” and “Forget about normality”. In parallel, monuments were destroyed and community centres and libraries burned down.

Such disappointment with the “system” points to a pressing question regarding the future role of the state: how is it possible to enforce the rules of public order while ensuring that they are perceived as essential to a modern civil society? When individual minds were inflamed and organized groups looted shops and destroyed urban landmarks, the state was close to irrelevance.

However, suddenly the coronavirus pandemic showed its ugly face. Protests suddenly stopped, and the sense of need for the state led the Chileans to develop what Adam Smith called “affection” for its institutions. They are willing to acknowledge that social life takes on dimensions that transcend politics and economics in the strict sense – namely, appreciation of living in a community and a sense of other people’s rights.

In recent decades, the Chilean state has been more concerned with promoting economic growth than with improving the less palpable principles of collective behavior. This led tothe recent violence against symbols of prosperity and even against symbols of Chile’s historical development.

The Chilean State has once again averted its own collapse, but in order to survive in the long term, it must embrace new forms – in particular, it must promote justice, public order and shared fundamental values. Perhaps the legitimacy of a future state could unfold as eudaimonia in the Aristotelian sense, a commitment to a good life for its citizens, imbued with the dedication to full participation in a political society.