RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – To predict that the political situation in Latin America will be marked by uncertainty and surprise is not risky, as at this time last year little was known about the existence of Juan Guaidó in Venezuela, for instance, and the popular protests that disrupted many countries were far from being a possibility.

The yet unclear consequences of this unrest will be a determining factor in the political revival that has taken place in the region over the past two years, with more than a dozen elections, including the main powers; countless fragmented parliaments – with the exception of the total power of Andrés Manuel López Obrador in Mexico – and the forecast by ECLAC (a UN body) that the 2014-2020 septennium will be the one recording the lowest economic growth in the past 40 years.

Ideologically, Alberto Fernandez’s victory in Argentina; Lula’s release in Brazil; the defeat of Uribism in the local elections in Colombia and the protests against Sebastián Piñera in Chile have given a respite to progressive forces in the region after conservative victories in Brazil, Colombia and Chile and the authoritarian course taken by Venezuela and Nicaragua.

After a century marked by the hegemony of so-called 21st century socialism, the pendulum between progressive and conservative forces remains balanced for the first time in a year in which presidential elections are scheduled only in the Dominican Republic and Bolivia.

Venezuela, focus of tension

Venezuela will presumably again be the focus of most tension in the region. In the country signaling that everything would change with the emergence of Juan Guaidó, nothing, in fact, did change.

At least on the political level: the economic situation remains critical, despite the dollarization that brings a lifeline to the wealthiest; migration is relentless – approximately five million people have left the country.

The conflict between Nicolás Maduro and Juan Guaidó remains unchanged. The former was able to entrench himself in power after a complicated year and the expectations generated by the president of the National Assembly, recognized as acting president by over 60 countries, have been diluted and his figure has been damaged, not only within Venezuela; the international community juggles to deal with the government of Maduro without this entailing a weakening of Guaidó.

Next Monday will be the first trial by fire for the young Venezuelan leader, 36. On that day he will have to referendum his position as the main leader of the National Assembly.

The Chavistas, who returned to Parliament this year with an opposition majority, have mobilized an offensive in recent weeks to try to weaken Guaidó’s support by trying to bribe several opposition leaders to change their vote. Since late 2015, the National Assembly has been in the hands of the opposition, so that Guaidó has, in advance, sufficient support, but at least thirty members of parliament are in exile and several dozen are threatened.

As of next week, a new scenario will open up – plus one – in Venezuela. The Chavistas are determined to call legislative elections, as should happen this year. Many believe that these will be set at the beginning of the year to entrap the opposition.

One section of Maduro’s critics maintains that there are no conditions for a clean electoral process, as they argued in May 2018 during the presidential elections won by Maduro and which were not recognized by the vast majority of the opposition and the international community. There are, however, broad groups of opposition leaders – some of them defended Guaidó last year- who believe they should participate in the hypothetical date.

The environment closest to the President of Parliament is cautious, it does not rule out another electoral scenario and that the clashes will again intensify.

The crisis in Venezuela goes beyond the Caribbean country and will certainly rock the entire region once more. On the diplomatic front, many eyes are on Mexico, which this year will hold the temporary presidency of the Community of American States and the Caribbean (ECLAC), the body that lived its best days under the protection of Hugo Chávez and Lula and which now the government of López Obrador wants to relaunch, partly as a counterweight to the Organization of American States (OAS), which he views with concern due to the role of protagonist exercised by its Secretary General, Luis Almagro.

Distrust in Mexico

Mexican diplomacy, which is not very active in the Venezuelan case, has taken a step forward in recent months, particularly with regard to the crisis unleashed in Bolivia by the resignation, after pressure from the military, of Evo Morales, to whom López Obrador granted asylum in his country before settling in Argentina. Domestically, the region’s second power faces a year marked by economic uncertainty after going into recession due to dropping income.

The completion of the new trade agreement with the United States and Canada is the main asset to give a little oxygen to López Obrador, who maintains broad popular support, according to all the surveys, but who still does not generate confidence in the business world to resume the country’s finances and thus be able to carry out his ambitious social agenda.

The economy will also be decisive in Alberto Fernández’s first year in office in Argentina, another power that, like Mexico, has decided to turn left, forming a theoretical progressive axis that is still far from materializing on paper.

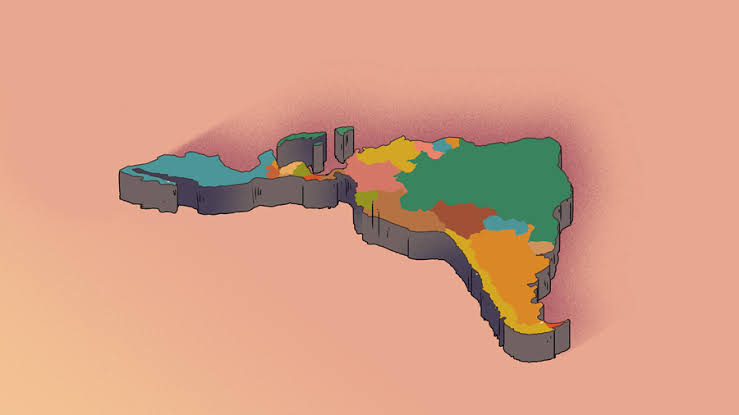

It is, at least for now, a counterweight to the great economy of Latin America, Brazil, governed by the far-right-wing Jair Bolsonaro, who has not yet been able to achieve his major reforms. The October elections will be a gauge to assess Bolsonaro’s wear and tear after two years of his victory and the support that Lula’s Workers’ Party may enjoy following the ex-president’s prison release.

The gauge on the power of popular demonstrations will come from Chile and Colombia, where protests are still alive, particularly against Sebastián Piñera’s mandate. In the Colombian case, the pressure is joined by Iván Duque to consolidate the peace agreements with the FARC and halt the advance of paramilitarism in the country.

The continued pressure and the gains that may result from it will show the strength of Latin American social movements and the leadership skills of politicians, that is, the level of governability in one of the most troubled regions.

Brazil, between reforms and fear of the streets

The great dilemma that the president of Brazil will face in 2020 is how to balance the reforms to liberalize the economy, in a way that will boost growth, but without harming many, or as few as possible.

The government wants to avoid lighting the fuse of discontent among the population that has caused so much damage in the rest of the continent while offering the electorate enough tangible achievements for the stock market to perform well in the municipal elections, before the 2022 presidential elections.

This is a major challenge. For the Chilean mirror in which the ultra-right-wing president and his ultraliberal Minister of Economy, Paulo Guedes, looked upon to carry out their deep economic reforms broke with street protests. Before or after, Bolsonaro must decide whether to rescue the tax and civil service reforms from the box in which he placed them in late November.

The dismantling of cultural and environmental policies is likely to continue – unless external pressure prevents it – and the conservative agenda will reach Congress, where it should meet resistance from politicians who want to become viable as an alternative to the center, like its current president, Rodrigo Maia.

Former prisoner Lula, 74, will be one of the protagonists of the electoral campaign, helping to promote podiums around the country and, as a result, attempt to forge a stronger Workers Party base in the municipal camps, unless some surprise occurs. Mayors and city councilors function as important electoral cables in the presidential elections.

Bolsonaro also faces challenges on his own playing field: maintaining a certain cohesion in an office that often includes rival groups and embodying the party he has just founded, the Alliance for Brazil, in time for the October elections.

For the time being, the party is little more than a brief manifesto that condenses the president’s nationalist, far-right, Christian and populist ideology and still requires formal registration with the Supreme Electoral Court (TSE).

He will have an eye on the investigations of his eldest son, Senator Flávio, suspected of corruption and money laundering. An Achilles heel.

Another dilemma awaiting him is the bidding for the 5G network, scheduled for this year. The pressure from Washington to exclude the Chinese company Huawei is intense.

Bolsonaro will be forced to choose between upsetting his admired Donald Trump or Beijing, his main trading partner, whom he mishandled until the presidency clearly saw that marginalizing China would be catastrophic for the economy. Or perhaps he is looking for an excuse to defer the bidding until 2021.