RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – The crisis involving Iran and the United States has pushed President Jair Bolsonaro further away from his vice-president, Hamilton Mourão, as well as from the military group that supports the government.

In addition, it has strengthened the radical wing that operates in foreign relations, in particular, the special advisor to the Presidency in the international area, Filipe Martins, and Minister Ernesto Araújo. Both were advocates of automatic alignment with Donald Trump’s administration in the clash with the Middle East country.

Over the past week, El Pais interviewed six sources from the Planalto Palace, Itamaraty and the Ministry of Defense, who reinforced this vision. They all spoke on condition that their names would not be disclosed.

The dispute between the two wings of Bolsonaro’s administration is now to determine who will be the substitute for the Brazilian ambassador to Iran, Rodrigo Azeredo, who is on vacation, and should not return to Tehran for health reasons.

At least three names have already been suggested to Minister Araújo, but the decision has not yet been made. As usual in cases of security crises, the Ministry of Defense is completing a rescue plan for Brazilian diplomats who are stationed in Iran. It will only be put into practice should there be a resurgence of the conflict, which does not seem likely to occur in the near future.

Since Iranian General Qasem Soleimani was killed by a US missile attack, Brazil has sent out distinct signals. First, President Bolsonaro reported that he would not be involved in the Middle East stir. Then he himself gave statements favorable to the United States. Finally, Itamaraty published a note advocating the fight against the “scourge of terrorism”.

The document said: “Upon learning of the actions taken by the United States in recent days in Iraq, the Brazilian government expresses its support for the fight against the scourge of terrorism and reiterates that this fight requires the cooperation of the entire international community without seeking any justification or relativization for terrorism”.

At first, the military wing of the government and representatives of the Ministry of Agriculture tried to convince the president not to declare his support for the Americans so promptly, fearing retaliation against Brazilians in Iran or losing business.

The theory was also defended by Mourão behind the scenes. Today, the Iranians are Brazil’s 24th largest trading partners. Last year, the trade exchange between the two countries reached the mark of US$2.3 (R$9.2) billion.

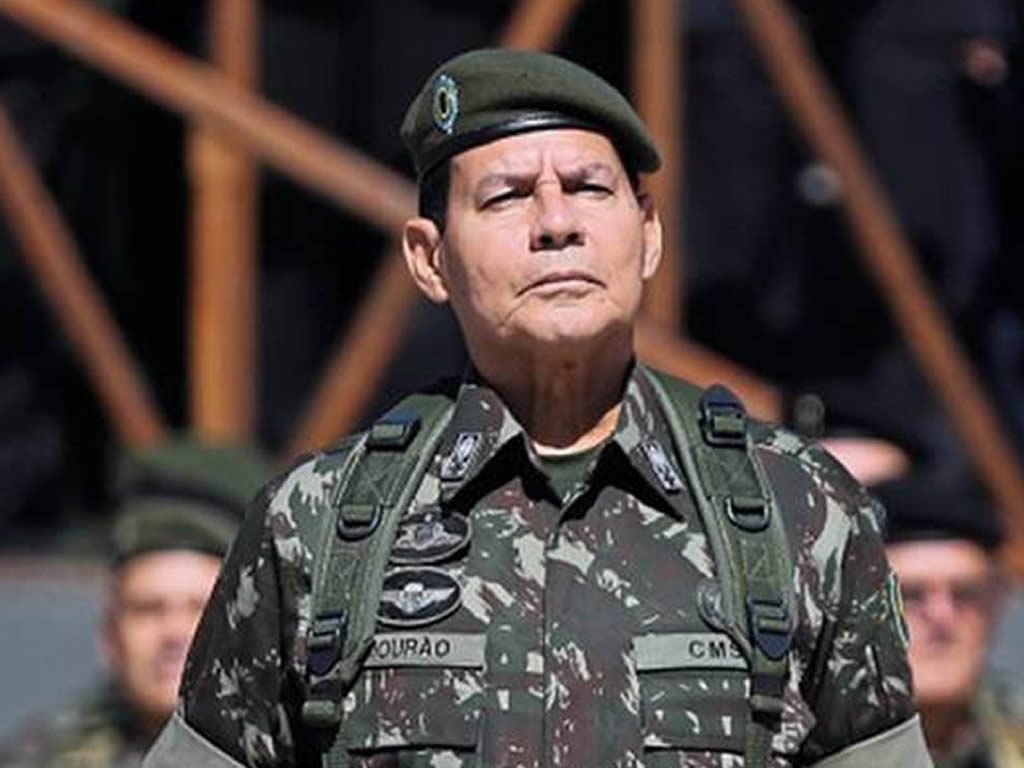

“The main loser in this whole story is Mourão. He always acted as a mediator of all conflicts. He is a person of open dialogue, but the President and Minister Araújo prefer to follow the United States blindly,” said a military officer with access to the Planalto.

The internal divisions seem to have a more political background, that is, a lack of coordination and divergence, rather than the aversion to a concrete risk. One assessment on the table is that Iran currently has too many enemies to be seriously upset with Brazil, despite Bolsonaro’s statements. The week past week and considering everything as it is, would leave few sequels.

In any event, the incident served to measure the current moment of relations between the Planalto and the vice-presidency. Since taking office, Mourão has always made himself available to foreign diplomats or businessmen for dialogue.

Early last year, Mourão’s agenda was marked by meetings with ambassadors and he was seen as a sort of safe haven in the face of the radical opinions expressed by Bolsonaro and Araújo. When the pair complained about their relationship with China or any Middle Eastern country, Mourão tried to host a representative from one of these countries to talk and raise a white flag (the vice president went to Beijing before Bolsonaro, for instance).

The same happened when Bolsonaro and the Minister of the Environment, Ricardo Salles, closed their doors to the Amazon Fund, which was essentially maintained by donations from Germany and Norway. Days later, the vice-president welcomed diplomats from both countries.

Since then, Mourão’s wear and tear has only increased, as has that of the military wing of the government. The fall of General Carlos Alberto dos Santos Cruz from the Government Secretariat and the departure of four other officers who held second-ranking positions throughout the year reinforce this gradual loss of support.

“There hasn’t been a break-up yet, but relations are shaken without a guarantee that there will be an improvement on the part of the president,” said one of the military officers heard by the story.

Another sensitive issue for the military, much more crucial than Iran, is Brazil’s handling of the crisis in neighboring Venezuela, where Bolsonaro made clear deference to the officers who support him. He sent Mourão as Brazil’s representative in the discussions of the Lima Group, a conglomerate of countries opposed to the Venezuelan regime of Nicolás Maduro.

Mourão was also scheduled to take diplomatic action in December: representing Brazil at the inauguration of Argentinian President Alberto Fernández, who was opposed by Bolsonaro. Other than that, the vice-president has spoken much less to the press than in the first months of his term and is more assiduous at events of the three armed forces, with little more than superficial statements.