RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – As the Climate Leaders’ Summit starts on Thursday, April 22nd, many eyes are on Brazil. Not always for the best of reasons, with the country expected to come under pressure to expand its environmental policies, forest conservation, and enforcement.

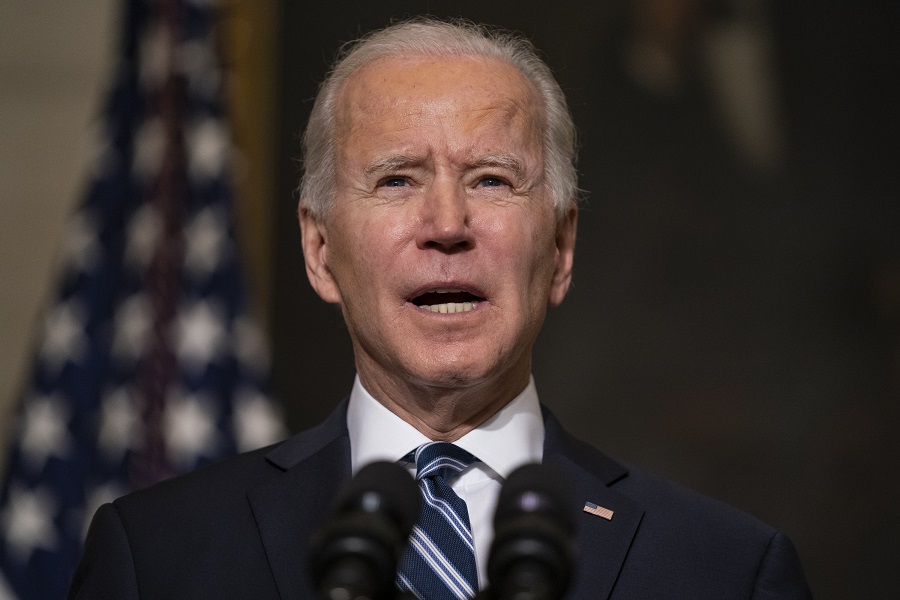

However, the summit should not have, not even remotely, a Brazilian protagonist – personified in the figure of Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro. The event, called by U.S. president Joe Biden, will bring together virtually more than 40 countries, among them the American arch-rival China, European powers, such as France and Germany, and important emerging countries, such as India.

Virtually all of them have an Achilles heel and many unfulfilled promises that they will have to discuss at the summit in order to address the global climate issue. In the Paris Agreement in 2015, 196 countries pledged to reduce carbon emissions in order to prevent the planet’s temperature from rising above 1.5ºC, preferably, or at most 2ºC by 2100 (from pre-industrial levels).

Since then, in just five years, the temperature has already risen 0.5 degrees, according to estimates. The diagnosis is clear: what has been done so far has not been enough, and more aggressive actions need to be outlined, starting with today’s summit.

Getting there invariably requires keeping the Amazon standing. But it is also about changing the energy matrix, reducing the use of fossil fuels, and making deep changes in the way countries produce and consume. And it involves, much more than Brazil, the great global powers, which are also the ones that pollute the most. During the American presidential campaign last year, the deforestation of the Amazon was mentioned by Biden in a critical tone. The leaders of the European Union, like French president Emmanuel Macron and German Angela Merkel, also mention Brazilian environmental policy in various statements.

According to specialists, Brazil, which has historically been a model to be followed and little criticized in international meetings, has placed itself in the crosshairs of a duel that was supposed to be centered on the giants.

“This is a fight of powers. Brazil did not contribute to the problem reaching the size that it is now. It has a renewable energy matrix and it is a country that has not even completed its development. It would not be charged this way in other situations”, says International Relations professor Helena Margarido Moreira, from Anhembi Morumbi, and a specialist in the role of environmental issues in geopolitical relations. “We put ourselves in the spotlight because of incompetence.”

China and the United States, the world’s two largest economies, are responsible for almost half of global carbon emissions. The whole of Latin America, including Brazil, produces less than 20% of China’s emissions alone. China emits more than 10 million tons of carbon, and the U.S., more than 5 million, according to 2019 data from the Global Carbon Atlas, a document organized by several organizations to map emissions in the world. Brazil does not exceed 500,000 tons.

This does not mean that the scenario is good. Last year, more than 11,000 square kilometers of the Amazon Rainforest were deforested (the target proposed by Brazil to the Climate Convention in 2009 was 3,000). Deforestation in the Amazon in 2020 is also 70% higher than the average of the previous decade (6,500 square kilometers per year).

In other biomes, the tragedy that culminated in the loss of about 30% of the Pantanal area, at the height of a fire that lasted more than 2 months, drew attention. The Cerrado, called “Brazilian Savannah” abroad, also had more than 700,000 hectares deforested in 2020, a 13% increase (more than 100 times the size of Manhattan, New York).

Moreira points out that deforestation is not only a characteristic of President Bolsonaro’s government, but that it has been growing at increasingly higher levels – and without concrete actions to change the scenario. “Brazil should be a model, as it has always been. It is not that it was ideal, it was always necessary to do more. But now it’s record after record in deforestation, lack of transparency, clashes with organized civil society,” he says. There is little positive to show at today’s summit. “You don’t have many facts that bring credibility to Brazil in foreign policy right now.”

International Amazon

There has been pressure on Brazil at other times in recent history. In the early 1990s, the Fernando Collor government also took office amid pressure to make the Amazon an international heritage. The discourse, defended at the time by names such as then democrat senator and future vice-president Al Gore, was that the Amazon was too important for the future of humanity to remain solely in the hands of South American governments (besides Brazil, the forest extends over five other countries).

Over time, Collor – also under pressure from Brazilian civil society during the period of redemocratization – demarcated indigenous lands, expanded inspection agencies, and used diplomacy to assure the world that the Amazon was safe. The following governments, to a greater or lesser extent, continued to strive to keep Brazil out of the negative climate spotlight.

This was crucial for the country to remain relatively free of pressure to this day as the global powers fought over who would have to cut the most emissions. And even after the crass errors of previous governments. Under the Dilma Rousseff administration, for example, the construction of the Belo Monte dam was widely criticized, especially by indigenous peoples – by names like the chief Raoni, who was repeatedly nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Even so, Brazil continued to receive, without further questioning, resources such as the Amazon Fund, created in 2008 and headed by Germany and Norway (and paralyzed since 2019 after clashes with the government). In the negotiations of the Paris Agreement in 2015, Brazil also played a prominent role, but in another way, helping to unlock an agreement that, for the time, was seen as the most ambitious until then.

Hat in hand

This time, Brazil is going to the Climate Summit asking for resources. In presentations over the past few months, the Ministry of the Environment stated that the country would zero carbon emissions by 2060 (10 years later than the commitment of most countries and companies at the UN).

However, it said that the date could be brought forward if Brazil were granted US$10 billion a year starting in 2021. To the German newspaper Deutsche Welle, retired researcher from the National Institute for Space Research (INPE) and former director of Policies to Fight Deforestation at the Ministry of Environment, Thelma Krug, said that Brazil today goes to world meetings in an awkward position, with a “hat in hand” to get money.

Deforestation is crucial in Brazil’s role on greenhouse gas emissions because, here, there is a peculiarity: Brazil’s emissions come mainly from the reduction in the forest area and from activities in the countryside, such as the use of land for agriculture and cattle-raising – due to cattle flatulence, for example, or deforestation to make way for pastures and, later, for plantations.

“Brazil is one of the few countries in the world that emit greenhouse gases because of deforestation and land use. The other countries have problems with coal burning and other pollutants,” says the former Brazilian ambassador to the U.S., Rubens Ricupero. “So it is important for Brazil to reduce deforestation in the Amazon.”

In the global race to ensure that the planet remains habitable, no one escapes the charges. The American government itself is under pressure: despite speeches by the Joe Biden administration that the fight against climate change will be a priority – and the pledge that its US$2 trillion infrastructure package will focus on the transition to a low-carbon economy – the Americans have a history of coming and going in this area.

The environmental agenda is also not unanimous in the country’s Congress. Former Republican president Donald Trump withdrew the U.S. from the Paris Agreement and did little for environmental advances in his 4 years in office.

This point should be largely exploited by China, while the Americans should pressure the Xi Jinping government to reduce the use of coal that has made the country a global power. In the context of the trade war with the U.S., the environment will increasingly become an agenda.

Source: Exame