RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Slow rattling gasps mark the beginning of the end. The dry COVID cough. Then silence. Eyes wide open. Then they reemerge like a drowning victim for one last breath. Relatives scream in desperation, and their cries wail through the thick air of the city. Just days before, a corpse on any street would have been appalling, headline news, a reason for alarm. Now, the acrid smell of death enveloped Guayaquil like a collective madness that was everywhere, bodies piled up inside hospitals, on the streets, some lying where they died. Vultures circled overhead. That is when it sank in. Guayaquil, Ecuador’s largest city and business center, was the scene of one of the fiercest COVID-19 attacks of the global pandemic. Beginning in mid-March, Guayaquil suffered a series of devastating blows. On April 6, the city suffered its worst day –778 deaths in 24 hours.

COVID-19 came in fast. On March 22, all hospital and private clinic beds were full, the emergency rooms were overwhelmed with patients with respiratory problems, and the entire health system collapsed. The next day the city registered 981 positive patients and 18 dead. Then all Hell broke loose with a hail of infections and deaths coming from every direction. All the screaming, and all the dead, and all the cries for help were enough to send anyone into shock. The soul of the city was stressed, its survival on the line.

In the center of it all, Mayor Cynthia Viteri wasted no time. By May 10, the bruised and traumatized city of 3 million, by then an estimated 9,000 citizens short, had its first zero-deaths day. In that short time, Guayaquil had moved farther, faster, and engaged COVID-19 on more fronts in less time than most cities on Earth. Viteri had faced virus, corruption, poverty, political crosswinds, and death. She does not claim victory, but by all measures she had contained the virus under the worst-case scenario—she had won the battle.

Why? Why? Why? Why?

Por que? Por que? Por que? Por que?– Why? – The mayor recognized the voice of her neighbor lamenting the death of a loved one. As she stood on high ground on her home, looking down on her city while guarding quarantine, Guayaquil mayor Cynthia Viteri felt the grief pierce through her in a way that forms a knot in her throat even today. She had seen the attack coming directly at her, infecting her husband and her son; she tested COVID positive too. Deaths everywhere. It was heartache that went on and on, she says. “It was confusion – a sea convulsing with more confusion,” says Viteri of her time at home in isolation managing the early fight against a COVID-19 onslaught.

Asked to recall these moments, Viteri closes her eyes and she is in the middle of waves as great as mountains that come from every direction, with every dry COVID cough, with every statistic, with every wail of an ambulance, with every death report. You can see it in her face as she tells how these swelling waves wracked anxiety, uncertainty, and despair in the form of a turbulent and unforgiving storm that spun around a city under attack, a city that was her responsibility. There was considerable work to do.

“And I am in one of those waves, and I need to –with my team, with the military, with the police, with all who help me – go and wrestle life from death,” recounts Viteri in a rapid expressive style that transmits her emotions as well as her thoughts with a passion that wells tears and talks through a shapeless lump in her throat, and then drifts into the soaring rhetoric of a politician.

The thing is, that is exactly what she did: she wrestled Guayaquil into life from death. In just 34 days Guayaquil went from 700+ deaths per day to zero, in one of the most remarkable turnaround battles in the world war against COVID-19.

“At first people did not pay much attention to the warnings of what was going to happen,” recalls Guayaquil attorney José Chiriboga-Hungría. “Until the deaths of hundreds of people happened, parties and activities were organized where there was a lot of crowding. This caused a contagion of many people. Because they could not be cared for in hospitals, they went to private clinics or treated their symptoms at home.”

Lack of treatment options and hospital deficiencies led to chaos, says Chiriboga-Hungría. “People died in hospitals or in their homes, the bodies laid for 3 to 7 days without burial. Cemeteries were not supplied to receive so many dead. People chose to take their deceased relatives to the streets to ward the smells and contagion.” That is what the world saw on its television screens.

Death by COVID-19 was not kind. It snatched people where it could, taking Guayaquileños in the streets, the avenues, the doors of the banks, stairs of hospitals, in homes from where people had to take their dead to the curb. Death ripped away the fabric of the city as it had never done within living memory. COVID-19 collapsed the medical system, the funeral system, the morgues; in the hospitals people had to walk through wrapped bodies without even knowing who was inside, recounts the mayor. “Those were the worst days of my life.”

The city’s worst day was many days, adds Viteri, a dynamic woman barely a year into her term as mayor when her city was suddenly in the grips of a Dantean descent. Guayaquil was a city in turmoil, its local government overwhelmed, a national government absent, people agitated, a hectic chaos in the street, public workers irate, exhausted resources, food scarce, general despair, no clear way forward, and speed of action is the only weapon at hand. So Viteri stopped looking for help elsewhere and took charge.

“Guayaquil was struck by the fact that from one moment to another the population was infected, and the authorities seemed powerless. People felt that they had no government to save them,” explains Guayaquil sociologist Cesar Aizaga-Castro, noting that the country’s president Lenin Moreno had taken refuge from COVID-19 in the Galapagos Islands as he was a member of a vulnerable age group.

“People did not believe the government or the media, the media hid information,” said Aizaga-Castro. “There was outrage that the true number of dead had to be outed by social media. People felt that nobody could protect you and that doctors were totally lacking in necessary equipment. This was a threat to the city.”

People found themselves in total chaos, adds Aizaga-Castro. “Suddenly, there was nothing certain and the population lost total confidence; the country did not have corresponding authorities to manage the situation of risks.” She did not have all the authority, says Viteri. As dictated by the country’s constitution, the entirety of the health and sanitation systems as the authority to collect bodies come under the jurisdiction of the national government, leaving the city in charge of water, sewer, trash, transportation, markets and the like. To get help, however, she says she relied on the saying that, when in need of a helping hand, one must first look at his own arm. Applied to the division of duties with the central government, that meant that she would assume the responsibilities in front of her and take charge of rebuilding the collapsed health, hospital, funeral, morgue, and cemetery systems. In the process, she changed the city’s support ecosystem and won the initial battle by stopping the COVID-19 charge, pushing it into retreat, and gaining control of her city.

Leadership and strategy

With taking charge came clarity of purpose as Viteri boiled down her mission to two simple problems: Save lives and feed the people. The strategy: coordination and discipline. Guayaquil was lucky, because Viteri had the support of business and civil society leaders, as well as the city’s former mayor and oft-times presidential candidate Jaime Nebo, who had run the city for 19 years, and whose leadership and contacts were crucial in the formation and execution of a Special Emergency Committee to generate strategies to reverse the crisis. The committee included Viteri, business titans, top professionals from a wide range of fields, doctors, pharmaceutical executives, health professionals, farmers, and members of civil society.

If this was war, this would be the city’s counterattack. The mayor went on war footing. This is the anatomy of the war plan: It begins with a mantra: “La única missión es vivir y comer.” – the only mission is to save lives and ensure food access— “Everything else is secondary.” They had to save Guayaquil, or nothing mattered. If leadership is the thing that wins battles, Viteri is steely in her determination. Focused on her two-pronged war strategy, she set out to marshal money and assistance, commandeering the yearly budgets of the city’s departments – including those for public works destined to commemorate the city’s 200th anniversary– and taking on responsibilities beyond her mayoral powers. To save lives, Viteri’s team began to look at death as one of three tactical areas: Attending to the dead, epidemiologic control, and attending to those alive. Each tactic engendered its own strategies.

The city moved to take care of the bodies in the streets and in the homes. Viteri addressed the funeral homes, morgues, and cemeteries shortages by securing freezer trucks outside hospitals, building cemeteries, and contracting a company to pick up bodies. In its first week it collected 500 bodies off the streets.

To attack the epidemic the city hired hundreds of doctors and medical personnel, spread them in satellite medical tents so that people would not have to go into the high-concentration areas of the city and risk infection. Viteri explains how they set up centers for medical attention away from hospitals overwhelmed by COVID, and even set up cost-free maternity clinics so expectant mothers could give birth without fear of exposure. Then came what she considers the coup de grace – the deployment of medical teams going door-to-door to find the virus. It is this step, between attacking the epidemic and attending to the living, that Viteri says she found the most important and effective element of her campaign. To literally chase the virus before it chases people into the hospitals and into death requires visits by special brigades that include a team of doctors, going to homes to evaluate early symptoms and get immediate attention to those in need so they would not worsen and arrive at the hospitals too late. “We met them in their houses instead of the hospitals.”

This required work on several parallel tracks. At first it was outfitting 51 health centers, field hospitals, outreach tents in peripheral areas so people would not have to come into the city, hiring some 500 doctors, adding 25 ambulances, turning the convention center into a hospital and finishing an abandoned construction project for a second hospital with 300 beds. When it was clear supply would be a problem, they city set up an oxygen-generating plant to supply piped-in oxygen to hospitals and to stem wild price speculation that had raised the cost of an oxygen tank from $50 to $1500 in places.

What happened was the result of a strategy that needed top-down leadership and coordination. The thrust of the response would be to avoid death by preventing and curing. While governments from Washington to Buenos Aires to La Paz were frantically purchasing ventilators, Guayaquil noticed that half of the patients on ventilators were dying, so they focused on treating people before they needed to be intubated. To that end, the effort focused on purchasing medicines for early-stage treatment and on keeping people off the streets to avoid infection. For the quarantine to work, Viteri wanted to make sure her people were fed. Ensuring food entailed a short-circuiting of the supply chain, cutting out middlemen and supplying neighborhood stores directly.

Prevent. Treat. Avoid death. To build that wall of defense, the cornerstone would be quarantine. To prevent the strategy from collapsing upon itself the Emergency Committee set out to address the social impact of staying home without an income.

Guayaquil, constantly on war footing, re-engineered supply chains with substantial participation from the private sector – logistics were provided by Cerveceria National, the country’s largest brewery, leading a group of other companies with the aim to ensure availability and to stop price speculation, they began by supplying nearly 5000 neighborhood stores. Donations from farmers provided some 150,000 fruit deliveries to the neediest neighborhoods.

Eventually in-home visits delivered one million food packages, vitamins, supplements, even diapers, while at the same time disinfecting, fumigating homes, leaving disinfecting kits, chlorine, and some 140,000 food kits, a 7-day supply, to 5000 families each week. This was the most important factor in the success of the entire campaign to stop death: going directly to people’s homes to identify symptomatic patients, get them early treatment to stabilize and strengthen them, says Viteri. “We get them early so when they get to the hospital, they have a better chance of surviving. We are chasing the virus. Instead of it chasing us.”

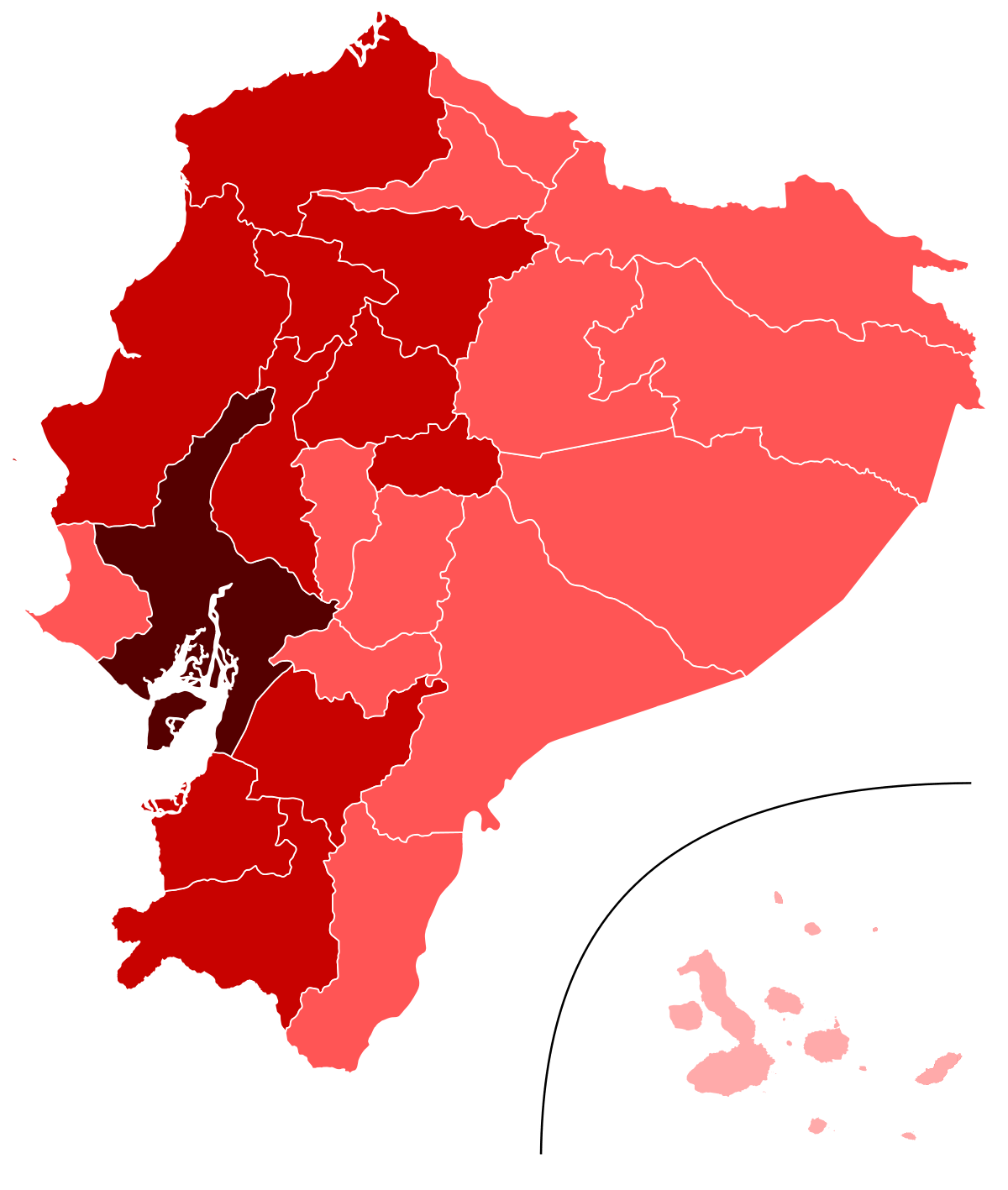

It is an elaborate campaign to chase the virus effectively. Viteri describes the work with a statistical survey group that samples 1600 homes across 17 districts of the city to identify where the virus is so efforts can be concentrated there to put down any spike. Nobody is waiting to be surprised.

This is all built upon a monumental effort that was mounted to outfit, retrofit, and supply all hospitals for the central government as well as all clinics public and private. They were all stocked, free of charge, with a cocktail of drugs for early treatment which included the controversial hydroxychloroquine, now deemed ineffective against COVID-19 by the World Health Organization but still used in early stage treatment in places around the world under medical advice.

A medicine-acquisition process was mounted and undertaken by a un-compensated team of the country’s top private sector leaders – pharmaceutical executives, buyers, importers, custom-clearing specialists who fanned their efforts across Europe, Latin America and China, acquiring medicines or the ingredients to make them. In this manner they kept hospitals always stocked. The work of the team charged no expenses, says Nebo.

Through all of this, single-minded and undeterred, the brigades continued to knock door-to-door, asking questions, sanitizing, chasing rats and chasing virus, rushing people to oxygen and early treatment before they get sicker. “People know that they will be treated, given proper medication, oxygen and food, and they will not be kept isolated from their families,” said Viteri referring to video connections made available to those kept in isolation at hospitals and clinics.

Telling the truth always – continuously – so that people know what is happening, that the situation is getting better or is getting worse is paramount, said Nebo in an interview speaking about citizen cooperation. “The public does not need you to give them false positive news because that is very dangerous, but neither does it need to be terrified into panic, because that is also very negative.”

“Two priorities,” repeated Viteri. “People did not want to go to public hospitals. They were afraid,” and with good reason, says Viteri. “They would go into the hospital and they would not come out, even when they died,” referring to the corruption that extended to making bodies “disappear” only to be found for a fee. “People lived the tragedy in their own homes, only seeking help when they turned gravely ill, often too late. We changed the strategy, we went out to find them beforehand, at early onset and intermediate stages to get them immediate treatment to avoid complications so they could be saved.” At the time of this interview they had assisted 102,573 patients who never went to a health center, and there had been 36 days of zero deaths. In that time, Guayaquil moved farther, faster, and engaged COVID-19 on more fronts in less time than most cities on Earth.

“But our vigilance continues,” said the mayor.

Viteri’s arsenal includes a telemedicine initiative so that people can keep up with non-COVID-19 related medical care while keeping them off the streets and providing doctors in vulnerable groups a way to continue to work while helping the war effort. Teleconsults are available through the city’s website for medical maintenance check-ups, mental health, and even addiction support.

In the post-mortem as to how and why the city ended up as one of the hardest-hit cities in the world, the start of community spread is placed by experts on a March 4 soccer game for the Copa Libertadores that gathered about 20,000 spectators.

“It resulted in massive contagion which led to the saturation of hospitals, institutions that collapsed and couldn’t handle the number who came for help; besides, they didn’t have enough equipment to fight the contagion. The reaction of the national government was late,” said Chiriboga-Hungría, criticizing the authorization for the game. He also calls out Viteri for a late response and controversial missteps early on. The mayor says she fought for her city like a mother fights for her children, out to do what it took to save lives, without worry about what people may say.

Today people are living their grief, says Chiriboga-Hungría. “In those moments people were suffering. Now we own this grief. We are still trying to assimilate what has happened. I would not say there is optimism; there is conformity…because we fought the fight and now this is our lot.”

Looking to the future, the city is relying on limiting such large gatherings, instructing its people on maintaining social distance, selective quarantines, curfews, the increased use of telemedicine, continued advice from experts around the world, and an app, SOSAFE, so that people can use to report emergencies or ask for help from every city department including trash collection. It also stretches into community monitoring, allowing neighbors of quarantined patients to sound the alarm if they see them venture out and put the community in danger.

In the end, the battle plan has succeeded, and there is one takeaway of global import: It is essential to take away the element of surprise, by surprising the virus in early stages, before people are too sick when they get to the hospital. It is the one thing Viteri wishes she had known before all of this started.

Having lost as many as 50 members of her city’s first responders during this battle, Viteri is resolute: “There will not be a single day in Guayaquil when we do not wrest our sons and daughters from the grip of COVID-19.”

The city’s 200th anniversary? It will be marked with a memorial to the 10,000 dead, says Viteri. The mayor’s eyes glimmer with water.

The city’s response to COVID-19 was not perfect, but during the battle emerged a very healthy respect for what the virus can do and a willingness to do anything it takes to defeat it. The mayor is not declaring mission accomplished. Vigilance, she says. “Everyday.” She says she will never stop. Having successfully managed the battle and proven it can be done, sadly she says. “Vigilance,” again. Unwavering. She looks up.