RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – The United States should remember that Russia has something to reclaim – like Alaska, State Duma Speaker Vyacheslav Volodin said a couple of days ago, in retaliation for Biden’s continued sanctions related to the war in Ukraine.

Pyotr Tolstoy, another of Putin’s top officials, followed Volodin’s statements with yet another idea, proposing that Russia should hold a “referendum” in Alaska.

In 1867, the U.S. bought Alaska from Russia for only US$7.2 million, just US$113 million in today’s dollars, and brought to an end Russia’s 125-year odyssey in Alaska and its expansion across the treacherous Bering Sea, which at one point extended the Russian Empire as far south as Fort Ross, California, 90 miles from San Francisco Bay.

Today Alaska is one of the richest U.S. states thanks to its abundance of natural resources, such as petroleum, gold, and fish, as well as its vast expanse of pristine wilderness and strategic location as a window on Russia and gateway to the Arctic.

A good deal for the Americans, who quickly recouped hundreds of times the purchase price. Why did Russia sell this prime piece of land?

ALASKA – A TREASURE CHEST

In the 19th century, Alaska, then still Russian, was at the center of international trade. In its capital Novoarchangelsk, which is now called Sitka, the Chinese traded in fabrics, tea, and even ice, for which the southern United States had great demand until the invention of the refrigerator.

Ships and factories were built here, and coal was mined. In addition, it was already known at that time that there were gold deposits in many places. So wasn’t it completely nonsensical to sell such a pound?

Russian merchants were attracted to Alaska, among other things, because of the seal bones, which were as sought after as ivory, and the valuable furs of the Kalan, a sea otter species, which could be traded with the natives.

This was the business of the Russian-American Company (RAK). This was founded in the 18th century by daring people – Russian traders, bold adventurers, and businessmen.

The company owned all of Alaska’s trades and mineral resources and was allowed to independently enter into trade agreements with other states, had its own flag and even its own currency, the “leather mark.”

The company had received these privileges from the tsarist government, which not only charged RAK substantial taxes for them but also had a stake in the company – RAK shareholders even included the Russian tsar himself and members of his family.

RISE AND FALL

“Supreme regent” of the Russian settlements in America was the talented merchant Alexander Baranov. He had schools and factories built and taught the natives to grow turnips and potatoes.

He had forts and shipyards built and expanded the sea otter trade. Baranov referred to himself as the “Russian Pizarro” in reference to the Spanish conquistador and was connected to Alaska not only with his wallet but with his whole heart – his daughter even married an Aleut chief.

Under Baranov, RAK generated significant revenues, turning a profit of more than 1,000 percent.

When Baranov retired from business at an advanced age, he was succeeded by Lieutenant Captain Leontiy Gagemeister, who brought new employees and shareholders from military circles. According to the Articles of Association, only officers of the naval fleet were now allowed to run the company.

The military immediately lent a hand to the lucrative business, but it was they who ultimately drove the company into bankruptcy.

The new “landlords” paid themselves astronomical salaries. For example, ordinary officers earned 1,500 rubles a year, which was equivalent to the salaries of ministers and senators, and the director of the company received a whopping 150,000 rubles a year.

At the same time, the prices paid to local hunters for furs were cut in half. The effects were disastrous: over the next twenty years, the Inuit and Aleuts slaughtered almost all the sea otters, depriving Alaska of its most important source of income.

At the same time, the natives became worse off and began to rebel. The Russians then took the coastal villages under fire from warships and put down the rebellions.

The officers tried to find other sources of income. At this time, the trade in ice and tea was started, but the would-be businessmen did not have a happy hand in this either – which would not have caused them to cut their own salaries.

In the end, the Russian-American Company could only be kept alive with government subsidies – 200,000 rubles a year invested by the government. But even that did not help anymore.

SALE AT A BARGAIN PRICE

Just at that time, the Crimean War began: an alliance of England, France, and Turkey was fighting against Russia. And it was perfectly clear that Russia was not in a position to supply Alaska, let alone defend it – the sea routes were controlled by ships of the enemy.

Even the planned extraction of gold was now suddenly in the stars. In Russia, it was feared that England could establish a blockade against Alaska and that they would end up empty-handed.

Tensions between Moscow and London increased, while relations with the U.S. government were better than ever. The idea of selling Alaska was, in effect, born simultaneously on both sides. Russia dispatched Baron Eduard von Stoeckl to Washington to conduct negotiations with U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward on behalf of the tsar.

While officials agreed on the terms of the trade, public opinion in both countries began to turn against the deal. “How can we sell land that has taken so much effort and time to develop, where telegraph lines have been established and gold mines developed?” the Russian newspapers complained.

“What is the United States do with this ‘ice chest’ and 50,000 wild Eskimos drinking fish oil for breakfast?” the U.S. press outraged, but Congress and the Senate also agitated against the purchase – to no avail.

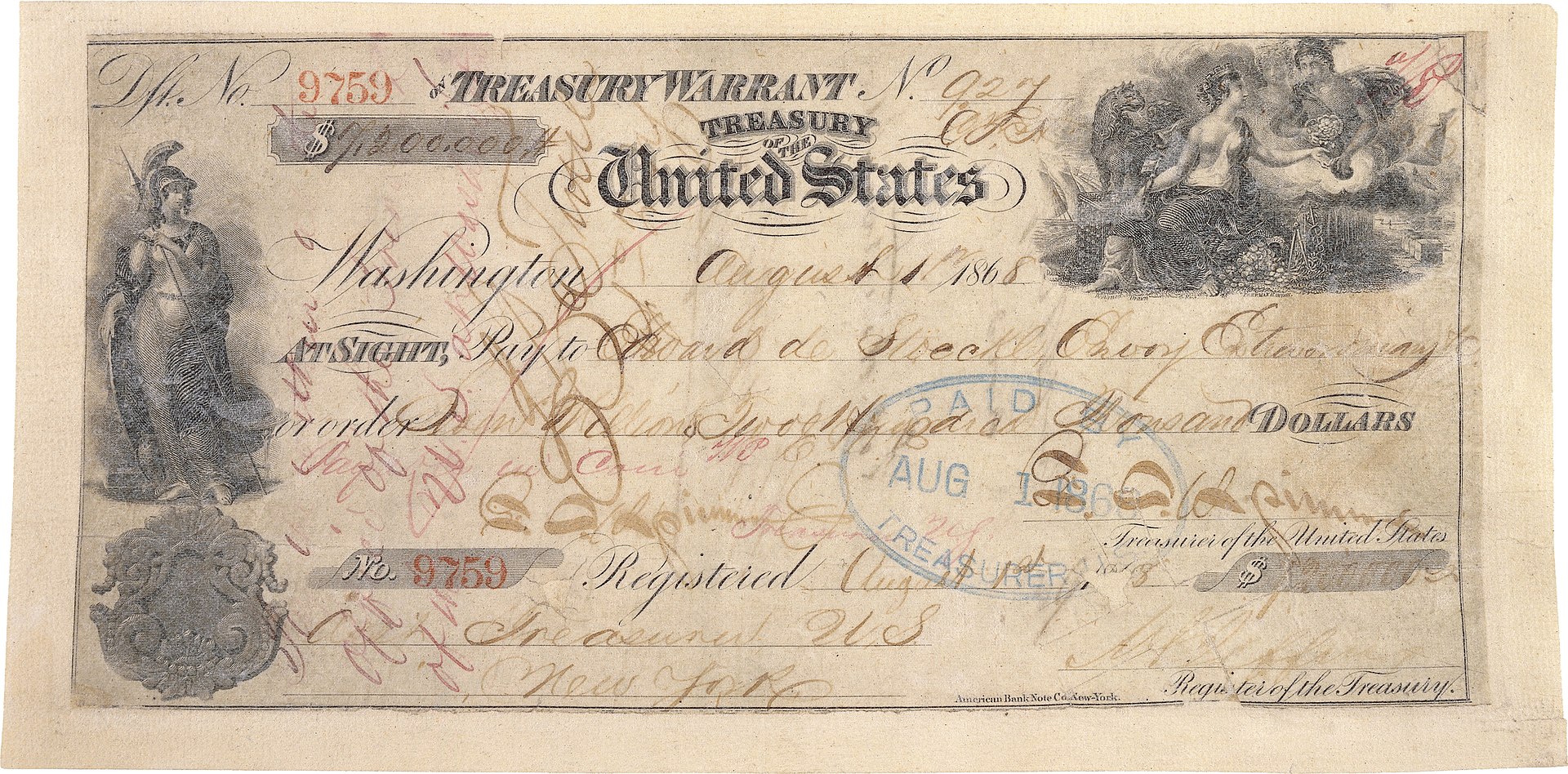

On March 30, 1867, the contract was signed in Washington for the sale of one and a half million hectares of Russian land to America for US$7.2 million. A purely symbolic amount, since even remote plots of land in Siberia, were not sold for such a low price per square meter. But Russia was under pressure and might have done even worse in this deal.

Not so much time has passed since then, and money has flowed out of the “ice chest” in torrents: in 1896, the Klondike gold rush began in Alaska, bringing hundreds of millions of US dollars in revenue to the United States.