Some of the damage done by climate change can no longer be repaired.

There would be no point in shutting down all greenhouse gas emissions now; we would still have drastic and irreversible consequences.

One of them is melting in tropical regions.

Glaciers in countries closer to the equator, which have warmer summers and more exposure to the sun than those beyond the tropics, are melting at a noticeable rate year after year.

Venezuela leads the sad race to become the first country in the world to lose all its glaciers.

Several other nations, from Colombia to Indonesia, Uganda to Bolivia, are close behind in this sad competition that reminds us that tropical and subtropical countries also have snow-capped mountains – but not for long.

With 15 peaks exceeding 4,000 meters in altitude, Venezuela is also an Andean country, besides being tropical, Caribbean, and Amazonian.

The northernmost portion of the Andes mountain range is located there.

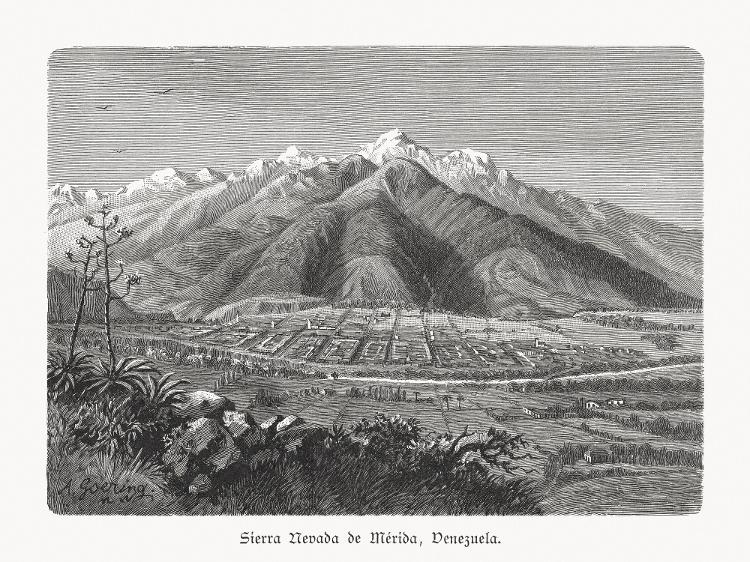

In Mérida, a state with cities of beautiful colonial architecture embedded in the mountains, at altitudes well above a thousand meters and temperatures ranging from 13ºC to 25ºC, the landscape has changed a bit.

The town owes its name to its Spanish namesake.

The founder, Juan Rodríguez Suárez, wanted to pay homage to his hometown, Mérida, in Extremadura.

A year later, in 1559, the city changed its name to San Juan de las Nieves, in an apparent reference to the geographical characteristics of the region.

It was short-lived; it was called Santiago de los Caballeros months later.

In the mouths of the people, however, the names were mixed, and it became Santiago de los Caballeros de Mérida – the official name to this day.

The Sierra Nevada de Mérida is a national park dedicated to the highest mountains in the country.

But an environmental protection area is powerless in the face of global problems. Fences and guards are useless against global warming.

Thirty-some years ago, the mountain range had five glaciers. Today, only one is left, and it is doomed.

In the last decades, two of the glaciers which could be seen from Mérida began to shrink.

Cracks shattered the ice; large blocks came crashing down. The rock became more and more exposed.

In 2017, Bolivar, Venezuela’s highest peak, dried up following the fate of La Concha, which lost its glacier in 1990.

The Humboldt Glacier remains the second-highest peak in the country at 4,925 meters.

It was the last to resist because the peak’s shadow protected it. But the situation is terrible.

In 1910, it measured 336 hectares. In 2019, the area was 5 hectares.

In other words, what had the size of a large urban park has been reduced to a few soccer fields.

It is no longer a question of if but when the glacier will disappear. Scientists estimate that it will be sometime this decade or the next.

A GLASS HALF FULL?

What would be just bad news for everyone turned into an opportunity for a group of scientists in Venezuela.

It turns out that the rapid retreat of glaciers turns out to be a unique window to analyze distinct eras of life on Earth.

Hundreds of thousands of years of ice covered that land, and now this is changing.

“It’s a gigantic transformation, on a geological scale, happening before our eyes,” physicist Alejandra Melfo told the “Atlas Obscura” website.

In 2019, Melfo and a team that includes experts in botany and ecology made expeditions to Mount Humboldt to observe how new life forms – lichens, mosses, larger plants, and mammals – emerged in this new landscape and interacted with each other.

For these scientists, the glacier’s shrinking process is a timeline of life’s evolution in this environment.

They created a map showing the shrinkage since 1910 and documenting the ecosystems at five points.

The further away from the glacier, the more diversity. In the closer places, there were far fewer signs of life.

Lichens, mosses, and some plants are the first colonizers, then comes the rest.

According to these scientists, the most surprising thing is the high collaboration rate between species.

For example, lichens trap moisture for the plants while acting as a windshield while the plants are still growing.

Furthermore, more than half of the 47 lichen species identified have never been recorded in the country before. Seven may even be new species.

These places that have lost their snow and ice cover less recently are likely to follow a similar path to areas where the glacier has disappeared, attracting larger plants and animals.

Far from being something to celebrate. But, as Jeff Goldblum would say, nature takes its leaps.

Life finds a way to thrive, which doesn’t necessarily include our species.

With informaion from UOL