RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – In Finnish, verbs are not conjugated in the future, which gives an idea of their attitude towards life. Their motto is “I can and I will do it”, as Finns are resilient people, the country was first dominated for 650 years by the Swedes and then 110 by the Russians.

Its inhabitants have instilled that they must be self-sufficient, and schoolchildren are self-sufficient due to a model with hardly any homework and assessments – inspired by their brilliant academic results – that undergo a constant transformation and that now grants them greater power in the classroom and responsibility in their educational progress.

They decide what they want to learn and how. Why tamper with a successful model? “The world doesn’t stop and neither do we”, say educator Ilona Taimela and Pia Pakarinen, vice-mayor of Helsinki and in charge of providing means and teachers to the educational centers of the capital, surprised by the question.

“Families question that we have changed something that is not deteriorated, but one must adapt to the needs. Helsinki has better results than Singapore, although 20 percent of students come from another country,” Pakarinen proudly says.

The world of which they speak is in constant conversion and children must be prepared for an uncertain future, in which there will be other professions -the machines will displace humans-, other technologies, and issues that are today unimaginable.

The Finns are experimenting and do not seem concerned about the fact that on December 3rd the PISA Report (Programme for International Student Assessment, which evaluates the knowledge in Mathematics, Reading and Science of 15-year-olds) will be published, which made them famous in the year 2000. “This did not matter to us before nor now,” says the vice mayor with a certain disdain.

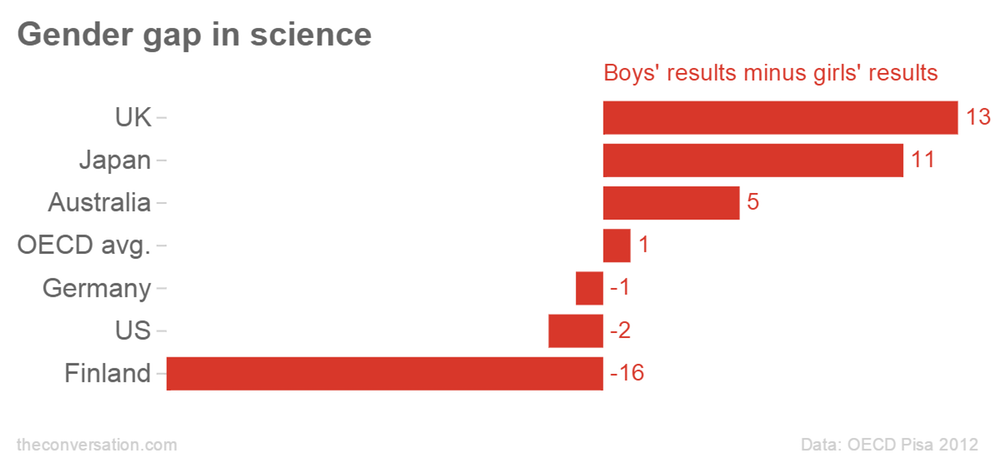

Finland has shared leadership in the PISA with Estonia and Asian countries (Singapore, Japan, and Taipei) in recent years. The latter has been successful at a cost of long study days and homework – many of which come back from school at 10 PM -, the antithesis of the Nordic model, which advocates free time and which is also 95 percent public.

In Europe, more and more schools, particularly primary schools, are working as in Finland, by projects, addressing a topic in a multidisciplinary way, but now the Nordics are going much further in a gamble that some consider risky as a result of the students’ prominence. They fear that so much independence will slow down their progression. “They have to be responsible for their own learning so that they are self-sufficient as workers”, emphasizes Taimela.

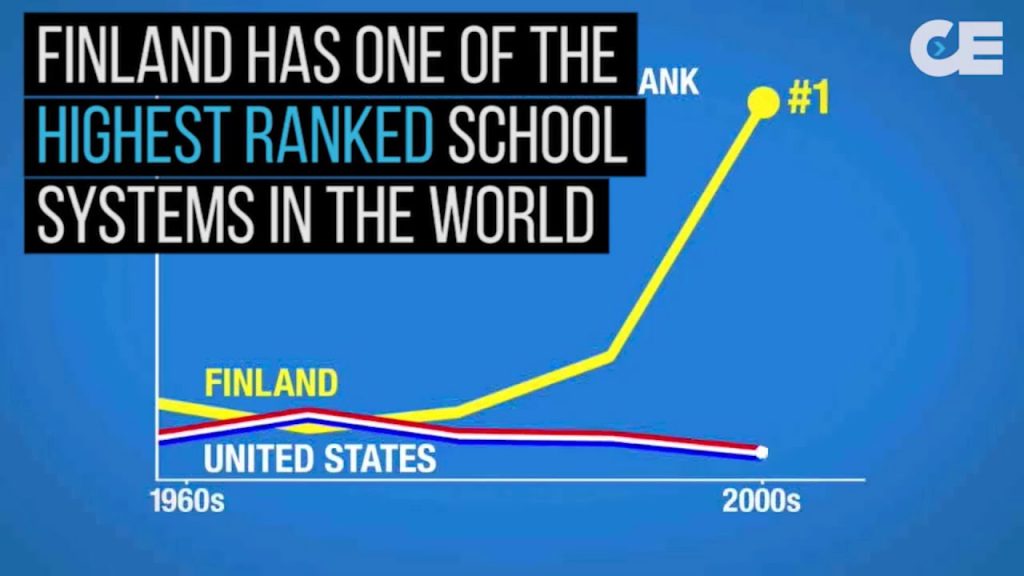

In the 1970s Finland was the first OECD country (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) that demanded that all students meet high standards that previously only involved elite students. And since then it has not stopped innovating.

Every 10 years the Nordic country approves a new primary school curriculum (from 7 to 16 years old, since 2015 a year of preschool is mandatory) and now they are implementing the 2016 model, which goes back to its original approach.

In 2021 they will begin secondary school (from 16 to 18 years old). Years ago many teachers chose to change books for laptops, to eliminate exams and notes and to work with projects, banishing subjects to use. A practice that impacted the international press for its brilliant results. But it is no longer a particular decision. It is required by law to apply “phenomenon-based learning” by creating a plan for each student.

“We prioritize that, in the face of traditional content, they acquire skills: learn to communicate, critical thinking, work in teams or solve problems,” says Taimela, coordinator of the Helsinki Education Week. Although then, aware that it is a thorny issue, she says: “You have to find balance. Some things are learned as before.”

In this process the teachers coordinate. “Nobody is a specialist in everything and everyone has a role in the team. We need professionals who are constantly learning,” remarks the vice mayor. “Kids sometimes go faster than you, and we get the most advanced to teach,” confesses teacher Tommi Tittalar, a specialist in creating learning spaces.

“It is not true that in Finland we throw away all the partitions. We need large places for certain times, such as in the morning when we plan the day together, but we also need separated spaces.”

“For three years the children decide what they want to learn in the projects. The first year we let them work on the topic they were most passionate about in life – there are those who chose Justin Bieber – but it was chaotic and impractical.

So now they agree between them,” says Tintti Hohti, deputy director of the Roihuvuori Comprehensive School, an imposing concrete center that welcomes 420 students, many more than expected.

At the end of the project, students share this knowledge with other classes. “The children listen better when the one telling a story is a colleague,” says the deputy director. “Children tend to be lazy, you have to arouse curiosity.” She does this with texts, images, and videos.

Hohti travels through the Roihuvuori neighborhood, surrounded by an idyllic snowy forest, to show that her children learn through phenomena how to lead a sustainable life. A group of 10-year-olds have agreed to experience living without electricity and are involved in this. That day, in the heated crafts room, they were divided into teams.

Some build a pyramid of firewood, others make shavings with a huge knife, while in the background they put mushrooms to dry on the roof, while the teacher instructs them how to make jams and preserves to last the winter.

Each school decides how to apply the model and it has imposed a minimum of two phenomena projects – lasting six weeks – on each course. A minimum for the most fearful teachers. In the more traditional subjects, the children also decide what and how they learn.

Valentín, 10 years old, son of an Ecuadorian and a Finn, shows on his laptop how, when the unit on the history of Egypt began, he textually told the teacher that he wanted to do an oral assignment, browsing the Internet and editing a video with his findings.

The teacher guided him in his learning with questions and the parents followed his weekly progress, questioning the teacher when they considered it relevant. The school expects him or her to self-regulate and self-evaluate.

But experts never tire of observing that they do not despise traditional means. “When we start a project, they don’t look it up on the Internet, but on paper,” Roihuvuori’s deputy director points out.

Each parent has an App developed by the Municipality that reports on their child’s tasks (usually the deadline for delivering a paper, not the daily lessons), what subjects they are taking that quarter and which also allows them to be in contact with the teachers.

Finnish success lies, according to education experts, in the fact that teachers are convinced that every student can achieve high standards and they convey this. And they believe that at some point they will have special needs.

“One of the things we are most proud of is that social differences are equal. And this is possible with positive discrimination, by investing more money in disadvantaged educational centers,” explains Liisa Pohjolainen, executive director of education in Helsinki.

From eight in the morning, there are usually extracurricular activities, but classes start at ten and end at one in the afternoon. The short day puts the independence of the little ones to the test since they take off their shoes at the door.

The children, in shifts and wearing aprons, collect lunch (everyone eats there for free) and clean the tables. There are duties for all of them. At Suomenlinna’s Elementary School, located on the island with the same name, eight-year-olds leave the lesson to approach the ferry dock and act as hosts to visitors to learn how to socialize.

The basic cornerstone of this “learning by phenomena” is the teachers, who have a great reputation and historically enjoyed the trust of their parents. Although families are afraid of the outcome of the curriculum that is starting with their children.

But this is not a leap into the void. During implementation, teachers undergo extensive training, in all schools there are several technological tutors and the support of the university, which assesses the entire process.

There are nine candidates for each position in the Teaching course. The academic record is assessed and there is a demanding entrance exam, but the most difficult part is an interview and a practical class because it is vital to have excellent teaching skills, not only to show wisdom.

Clearly, knowledge is not lacking either. As in Japan, an average Finnish teacher has more knowledge of mathematics than average college students, unlike neighboring Sweden and Denmark, according to the OECD’s PIAAC (Adult Skills Assessment) report.

As a result, their educational independence is full, but this does not mean that they are not supervised by other colleagues. The classroom is not regarded as something private.

Teachers recognize that the challenge is how to examine this learning through projects. “We have assessments that differ among children, of course. They are not meant to give a grade, but to check that there are no comprehension issues and, if so, to take action,” says the director of education. “Progression and motivation are assessed and, at the end of the course, they can be graded on their learning outcomes,” she continues.

After the ninth grade (15 years old), grading is mandatory and, contrary to the myth of lack of pressure and competition, at the end of secondary school they are submitted to a difficult final exam. Entering University (free) is also a long-distance race, and many strive more than once.

The fact that the whole city is considered a place of learning is the culmination of the project. During school hours, public transport is free for children and they take to the streets. In the Helsinki City Hall one needs to get around dozens of jackets of five-year-old children visiting the building. The mayor, Jan Vapaavouri, thanks the visitors. “Education is the passport to the future,” he said at the HundrED.org summit, where 100 educational innovations were introduced.

“When the city makes decisions that affect children, it listens to what we have to say. We know the politicians, we write statements… We can contribute and make it come true,” says Milja, 15.

Helsinki has a consultative council of youths and minors over 12 can vote on the allocation of part of the budget earmarked for them. Because in Finland children are not the future, they have the present in their hands.