RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – A research group from the School of Medicine and Pharmaceutical Sciences of the University of São Paulo (USP) is excited about the development of a Brazilian vaccine in nasal spray format to immunize people against the novel coronavirus.

In its latest trials, the results of the formula developed by USP in partnership with the Heart Institute (InCor) were positive. Should all proceed as planned, the vaccine may be available as early as 2021.

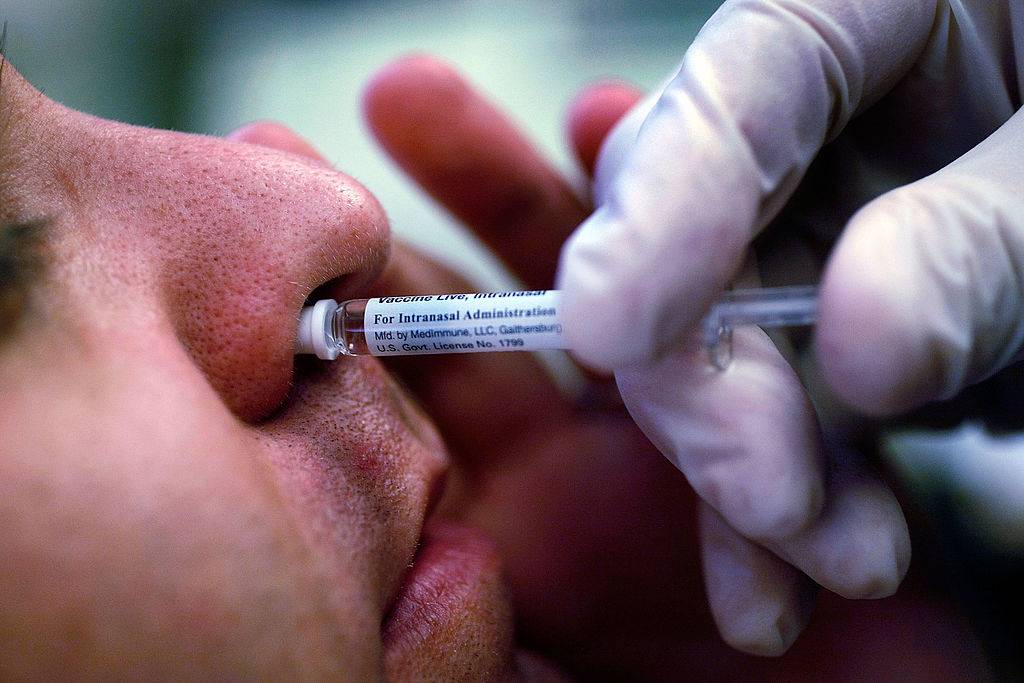

The difference between this Brazilian immunization therapy and other vaccines being developed in the world, such as the vaccine developed at Oxford University, in the United Kingdom, or the one produced by the Chinese laboratory Sinovac, is that the domestic vaccine will not be injected. Instead, it will be administered using a spray positioned inside the nostrils. The aim is to allow the immunological compound to act more swiftly.

“The vaccine applied by a nasal spray allows the generation of two types of antibodies and not only the one generated when the vaccine is injected,” explains Marco Antonio Stephano, professor at the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences at USP and in charge of the project.

According to the expert, intranasal administration enables the vaccine to reach the upper airways and lungs, which causes the immune system to act at the onset of infection.

Once ready, which could occur in the second half of 2021, the vaccine should be administered in four doses (two in each nostril) with an interval of a few days between applications. This allows the nanoparticle compound to remain long enough in the patient’s body when coupled to the nasal mucosa to boost the immune system to fight the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

For now, the Brazilian vaccine is still in the pre-clinical trial stage. This means that phase 1 and 2 trials have not yet begun. The first phase of clinical trials should begin by late November.

Should this occur as planned, the second phase would begin between January and February 2021. The third phase would follow. This is the stage when the vaccine is applied to thousands of people, and many projects sink.

In an optimistic scenario, where the vaccine can be approved in all the required clinical trials and receive a positive evaluation by health agencies, the researchers hope that the immunization therapy developed in Brazil can be ready by June next year. Thus, the nasal spray against Covid-19 would only reach the population after the injectable vaccines, which may be available on the Brazilian market as early as December this year.

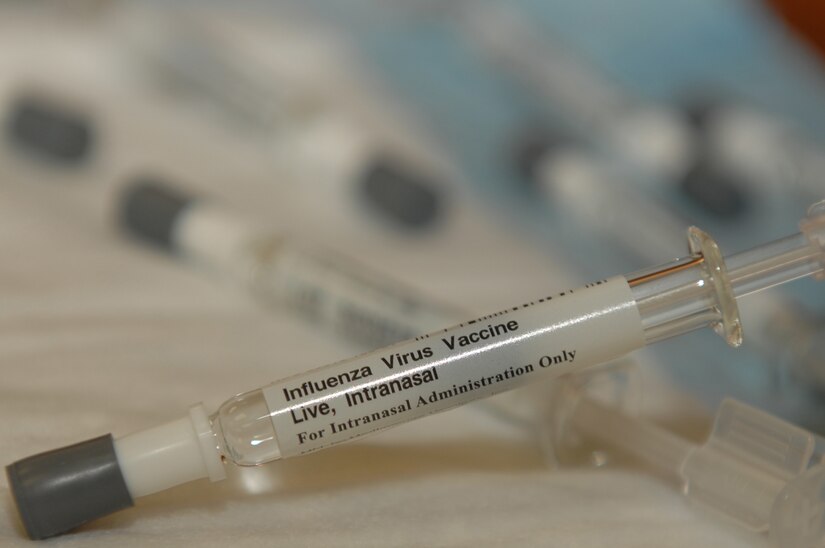

“The development is a little slower than the injectable vaccine because so far there are few vaccines administered in nasal spray form,” says Stephano. The researcher mainly refers to FluMist Quadrivalent, a vaccine produced by Anglo-Swedish pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca – which is Oxford University’s partner in producing a serum against Covid-19. FluMist is applied by nasal spray and protects against the influenza virus.

It should be noted that the vaccine spray format was also used to immunize the H1N1 virus in the United States. It was in 2009, during the swine flu outbreak. At the time, the serum was produced by MedImmune, an AstraZeneca unit.

The vaccines being developed for injecting and in their third testing phase, or which are scheduled to be made available, as in the case of the Russian vaccine, the formulation process is simpler. For instance, Oxford’s uses the creation of immunizers against Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) as its basis.

Independence and spray savings

There are advantages to using a nasal spray in the administration of immunizers. “The adverse reactions are much less than in injectable vaccines,” says Stephano. According to the researcher, the most severe reaction that can be obtained with the nasal spray is called Bell’s paralysis.

When this occurs, there is paralysis of the facial nerves. It is considered a rare reaction, with less than 150,000 cases per year in Brazil. The treatment is done by physiotherapy.

Adverse effects are still being studied in injectable vaccines against Covid-19. In the United States, Ian Haydon, a volunteer who has agreed to take part in Moderna pharmaceutical trials, said he had a reaction that prevented him from being able to lift his arm.

He also reported feeling nauseated, had a fever of 39.4°C, and even passed out. Haydon was in the group of subjects who were administered the highest dose of the vaccine.

With minor adverse reactions, the nasal spray may be a less aggressive form of administering the vaccine than the injectable one. To such an extent, that AstraZeneca’s nasal flu vaccine, for instance, is eligible for people in the 2 to 49 age range.

On the other hand, trials for AstraZeneca’s Covid-19 vaccine are being conducted in children aged between five and 12. Trials will also be conducted in Brazil, but only with people over 18 years of age.

The financial aspect must be taken into consideration. According to Stephano, the production of the four doses of the nasal spray vaccine costs approximately R$100 (US$20). It is a relatively lower amount than the US$40 established as a reference for the price of the vaccine being developed by American pharmaceutical company Pfizer with the German BioNTech.

The production of a vaccine in Brazil is critical to allow the country not to be dependent on international laboratories. “If tomorrow there is a diplomatic rupture in Brazil with some market producing the vaccine and a blockade to the country, we have a technology that is developed nationally,” says Stephano. “We need to have several vaccines on the market. ”

On another front, the nasal spray vaccine could be a solution to a problem that arises with the worldwide demand for a serum against the novel coronavirus: the shortage of syringes. In late July, the European Union warned that “there may be a shortage” of syringes, ribbons, alcohol, and other items and equipment used for the administration of injectable vaccines.

In Brazil, the shortage of syringes is currently a concern for the Brazilian Association of Medical and Dental Articles and Equipment (ABIMO). According to the association, municipal, state, and federal governments must be prepared to order the purchase of syringes.

“Syringes are not produced overnight,” said a spokesperson for the association. Brazilian production amounts to ten million units per month, but it could increase according to demand. This, however, requires advance planning.

Lack of incentive

The production of a Brazilian vaccine could be further advanced. The issue is that even the partnership with InCor lacked incentives, mainly financial, to expedite the process.

For Stephano, this is a reflection of the financial crisis faced in recent years and which has worsened since 2013. “When there are economic problems, the science, technology, and education areas are the first to suffer funding cuts,” he says.

A survey conducted by the Brazilian Society for the Progress of Science shows that the budget to invest in science and technology in Brazil was R$4.7 billion. The amount, which discounts resources already earmarked for labor and compulsory expenses, is 38 percent less than it was in 2019.

Ildeu Moreira, a physicist and president of SBPC, showed concern. “The situation is not encouraging at all. We have a very difficult picture ahead of us,” he said in December 2019.

Stephano has demanded greater involvement from state governments. The main criticism was directed at the São Paulo state government, which operates through the Foundation for the Support of Research in the State of S. Paulo (FAPESP).

When questioned, FAPESP reported that it is supporting three projects for the development of Brazilian vaccines against the coronavirus. One of them is from USP’s own Medical School. In June, the research entered a pre-clinical trial phase with mice.

In a note, FAPESP stated that “researcher Marco Antonio Stephano is currently supported by FAPESP to conduct two researches for the production of vaccine antigens of influenza virus types H5, H7, and H9 through the synthesis of “cell-free” animal protein. These projects, however, are unrelated to the production of a vaccine against the novel coronavirus.

Source: Exame