RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Mexico reaches the end of the year up to its neck with the violent events of October and November. On Sunday, December 2nd, several clashes between police officers and suspected criminals in Coahuila, in the north of the country, left 21 dead, including four police officers.

This is only the latest incident of this dark two-month period, which counts its weeks in killings, ambushes and multiple murders.

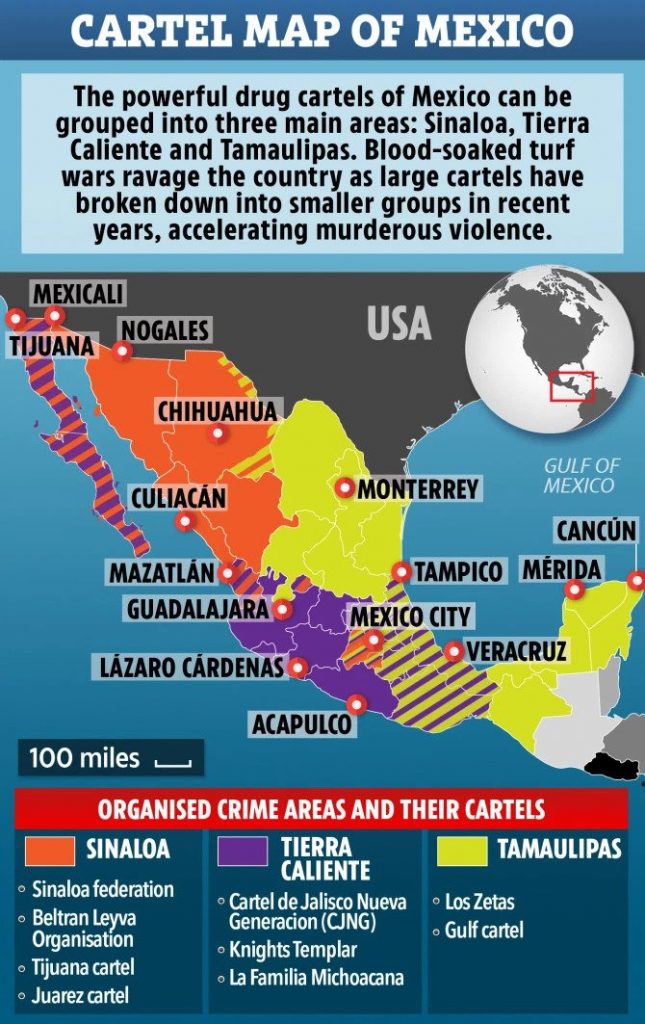

The slaughter of Sonora – nine dead, including six children -, Guerrero – 15 alleged delinquents killed in a gunfight with the Army – and Michoacán – 13 police officers shot -, as well as the relentless murder of women and youths, and the shameful mistakes in Culiacán’s failed operation against the son of drug dealer El Chapo Guzmán, are illustrative of the hardships the government of Andres Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) is facing in large areas of the country.

The only positive aspect of these months is that the murders have stopped growing and have stabilized at around 2,900 or 3,000 per month. The question now is whether this is a mirage or, on the contrary, a solid pattern in the process of consolidation.

This Sunday, celebrating his first year in office, López Obrador commemorated what he believes to be a “paradigm shift” in security policy. The president said the violence the country faces began on February 2nd, 2007, when President Felipe Calderón (2006-2012), at an event in the state of Michoacán, ordered the army to leave the barracks and counter drug trafficking.

“The military high command told the officers: ‘Finish them off, and we’ll take care of human rights. The best evidence is that this six-year period [the duration of a presidential term in Mexico] boasts the greatest mortality in fighting since the 1910 [Mexican] Revolution,” the president said. And he quoted the figures of the 1,800 clashes recorded between 2010 and 2011, which left 231 wounded, but some 2,500 dead.

“This absurd and unbalanced strategy will never be repeated,” announced the president in the Zócalo, the Mexican capital’s main square.

Before taking office in late 2018, López Obrador announced that his plan to contain violence consisted in attacking the causes – corruption, the lack of opportunities and jobs and the precariousness of education and health – on the one hand, and, on the other, reshaping the so-called war on drug trafficking initiated by Calderón.

With social programs, said López Obrador, he would address the causes. Faced with the failure of previous governments in terms of security, his plan was to create a new corporation called the National Guard.

The new body would replace the Federal Police, with the support of the military and naval police. The idea was criticized by civil society organizations that saw in this project a covert militarization of public security.

Despite the criticism, López Obrador imposed his criteria, and Congress passed the constitution of the Guard. Without the corruption intrinsic to the Federal Police, the new National Guard would mobilize tens of thousands of officers throughout Mexico, and the violence would drop – at least that was the plan. The results would be noticed in six months, the president promised.

A year later, however, the situation remains the same – or worse. López Obrador’s social programs have been running for months, as has the National Guard, but the results have not materialized. More worryingly, the security system shows an alarming lack of coordination.

Criticism of the Secretary of Safety, Alfonso Durazo, has been very harsh and unrelenting in recent months, particularly after the clashes in Culiacán, when an army elite group tried to arrest Ovidio Guzmán, apparently without warning their superiors. And then again after the slaughter of three women and six children of the Mormon Langford-LeBarón clan between Sonora and Chihuahua in November.

For historian Froylán Enciso, “what Culiacán showed, and then the case of the LeBaróns, is that Durazo is a mediator between different security policy management groups, which have different levels of resistance to change and different political positions. In other words, there is no unified group carrying out security policy, but a coalition of many figures”.

Analyst Alejandro Hope adds that “There is an imbalance between the powers that the law confers on Durazo and the power that it exercises. Because, in real terms, he commands virtually nothing. And then, I believe he doesn’t want to be there. What happened in Culiacán shows Durazo’s relative fragility”.

The sense of frustration in terms of security is possibly one of the most painful for the Government. Before taking over the presidency, López Obrador organized forums throughout the country to listen to the victims. He took as his flag two dramatic topics: the investigation of the attack on the 43 students of Ayotzinapa and the crisis of missing persons. And not even in these two subjects did he achieve much success.

Dawn Paley, the author of Anti-Drug Capitalism, followed the steps of the new National Search Committee, the body that closely oversees the Executive’s efforts to fight against the disappearance of people. “I feel that we are experiencing continued security in relation to what has been done in previous years. The discourse has changed, there is an attempt to say ‘let’s not do the same thing anymore’, but the facts show a continuation. The homicide rates are the same or higher; in terms of disappearances, they are not giving the victims a leading role, they are not allocating the resources that many thought would be there”.

Froylán Enciso, a PhD in history and expert in the evolution of drug trafficking in Mexico, says that “the first year of government leaves as a balance of great ideas in general terms, which we have been advocating for decades: more focus on the causes, to abandon the strategy of beheading criminal organizations. However, there is a double issue: addressing the causes has long-term effects, not immediate effects. And, on the other hand, there were problems with the implementation of social programs, which did not work as a clear preventive strategy”.

The Triple War

More than a transitory problem, homicidal violence represents Mexico’s list of structural ills and the wrong solutions of several governments. Since 2007, the annual homicide rate has increased steadily, except in the three-year period 2012-2014, the last years of the Calderón government and the first years of his successor, Enrique Peña Nieto.

Hope, an official with the state intelligence agency at the time of Calderón, recalls that that period coincided with a certain tranquility in Ciudad Juárez and Monterrey. “What worries me now are our problems to understand all this, we want to apply national logics to hyperlocal dynamics. Homicides have been stabilized at a very high level, and we do not know why that is happening”.

For a long time, violence in the country has been explained as a triple war, on the one hand between criminal groups, and on the other hand between these groups and the state; as a war on clear sides, without nuances or impurities. Reality has shown, however, that organized crime has seeped into the police, the Armed Forces and the courts. This happened when it was not agents of the very corporations organizing the criminal world.

According to Paley, organized crime is over-dimensioned. “This notion that crime has more power than the Army is a fantasy. The Army, the Navy, the Federal Police have received billions of dollars in weapons in recent years. The backbone of violence comes from the state forces, the Federal, the Army and the Navy. What we can say with certainty is that these criminal groups are still on the streets – now as a National Guard – and this is the main problem”.

Enciso adds that there is a gap between the crime representation and the reality. “What we see today is that we are increasingly aware that traffickers are actually youths without opportunities. In other words, those killing are our neighbors, they are not mythical beings, they are children of people, they have families, needs… In the last year we have seen an awareness building process in this sense. The criminal has been demystified”.

Knowing the nuances, the trouble is that violence persists. The apparent chain of apathy and disloyalty within the security system not only prevents decoding with certainty what is happening in Mexico, but also hinders finding the solutions. The pressure is enormous, particularly after US President Donald Trump’s announcement to include the “Mexican cartels” on the State Department’s list of terrorist organizations.

Durazo and other Mexican government officials rejected the idea, arguing that it was interventionist. But it is curious that Trump’s threat points precisely to the problem that the experts consulted point out: what is crime now, and what exactly is being fought against. If Trump finally decides, which cartels will he include on the list? And if the included cartels are indicted or investigated for working with a police or military corporation, what will the US government do?