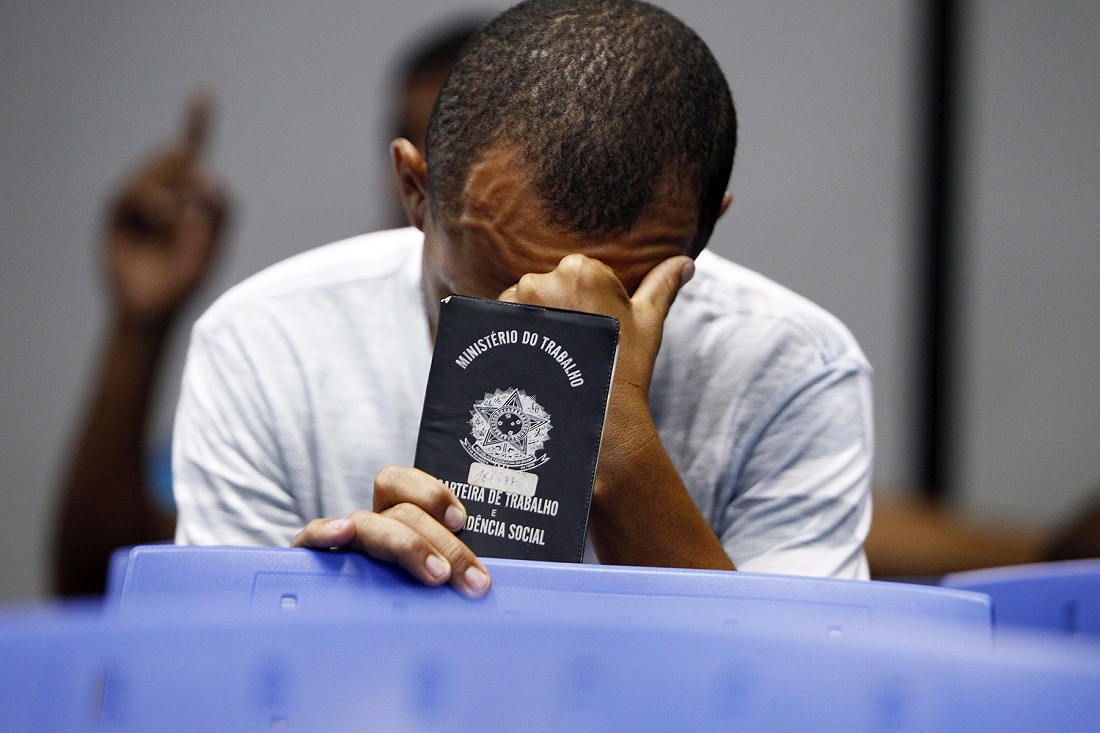

RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Informal work in Brazil is growing persistently, breaking record after record. If, on the one hand, this means that there is room for those who need to make a living, on the other hand, the slow upturn in formal employment, with a signed worker’s record book, is a sign that a robust recovery in the labor market is likely to take time.

Given the current pace of job openings, the unemployment rate should be brought to pre-crisis levels by 2024, experts heard by the story say.

In their view, the continuous increase in informality at a much faster pace than the generation of formal jobs suggests that there is still concern among entrepreneurs over the economic upturn, which is holding back investments and the resultant generation of jobs.

“Investors and companies are still unsure about the economic comeback. So, nobody wants to take a strong step and hire formally”, says Juliana Inhasz, an INSPER (Institute of Education and Research) economist.

“If there is no prospect of lasting growth since the reforms take time to come out and the economy’s signals are changed, the market ends up investing in a contract ‘with less commitment’,” she says.

According to data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), released on Friday, September 27th, informality broke the record in the quarter ended in August, with 38.8 million Brazilians in this condition.

The number considers employees from the private sector and domestic workers without a signed worker’s booklet, self-employed workers and employers without a National Register of Legal Entities (CNPJ) and auxiliary family workers.

This quota represents 41.4 percent of the working population, the highest rate since the IBGE began to measure this indicator in 2016.

The unemployment rate continues to drop, but at a timid pace. In the quarter closed in August, it was 11.8 percent, against 12.3 percent in the three months to May, 12.1 percent a year ago, and 12.6 percent in August 2017.

“We had a one-percentage-point drop in unemployment over the past two years. This is very little. It is good to see a drop, of course, but we are far from reaching the pre-crisis levels,” said Laísa Rachter of the Ibre/FGV (Brazilian Institute of Economics of the Getúlio Vargas Foundation).

For Cosmo Donato, an economist at LCA Consultores, the country’s economic situation has forced people who didn’t work (either because they studied, had some income saved or because they didn’t need it) to look for work, increasing the total number of unemployed people in the country.

In his evaluation, this scenario should continue for a long time to come and this will cause a drop in unemployment to occur slowly and gradually. “We project that this rate will only decrease in the annual average below ten percent in 2024,” he says.

Unemployment in Brazil was 6.7 percent in the quarter ended in February 2014. Three years later, in 2017, it reached 13.2 percent, according to IBGE data.

Donato says, however, that observing data from employed and unemployed individuals is not enough to understand the labor market scenario. He states that the length of search is also relevant.

Along these lines, the latest Status Letter by IPEA (Institute of Applied Economic Research), published two weeks ago, shows that the continuing crisis and the slow upturn have fed long-term unemployment in the country.

According to data from the IBGE’s Continuous National Household Sample Survey (PNAD), IPEA researchers show that in the second quarter of this year, 26.2 percent of unemployed workers had been in this situation for at least two years. In the same period in 2018, this figure was 24.4 percent.

However, it is not only the lack of jobs that shows that the market is taking time to react. Both formal and informal jobs send out signals on the difficulty of resumption.

Adriana Beringuy, an analyst for IBGE’s work and income coordination, says this is clear in average wages. “Even with more people working, this growth was not enough to increase the mass of economic incomes, because people are entering at lower wages”.

In the case of jobs in the public sector, openings are precisely those that pay from one to two minimum wages and require less qualification.

According to data from CAGED (General Register of Employed and Unemployed), in August 42,400 formal jobs were opened with salaries of up to one minimum wage. Another 99,800 openings that month offered salaries of up to two minimum wages. Simultaneously, the balance of jobs with higher incomes was negative.

The age group that has been most favored by formal jobs includes youths who have just entered the market and are aged between 17 and 25.

Juliana Inhasz of INSPER, recalls that a large number of people in search of a job also pushes wages down.

The average income has not changed much. It went from R$2,297 in the quarter to May to R$ 2,298 in the three months to August, according to IGBE data. In August 2018, it was R$2,302.

Donato, of LCA, recommends caution regarding the notion that informality is a phenomenon of the modern world that is gaining ground in Brazil. In part, he says, it is true that there are new forms of professional activity, but the phenomenon occurs compulsorily and is still poorly structured in the country.

“The crisis in the past may even have brought about a structural change in the labor market, but since it is followed by a slow recovery, it is causing a shortfall in the supply of higher-quality jobs”.

Informal jobs also tend to offer smaller earnings and their spread contributes to reducing the size of workers’ earnings.

“People want to go back into the labor market and no longer demand a higher wage than they would be able to,” says Inhasz.