RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Isabel Brito, a 58-year-old widow, is used to taking care of others. For years she took care of her husband after a stroke, visited bedridden patients, adopted an elderly neighbor who lives by herself and who, according to her estimates, should be around 90 years old.

This is not unusual in a Brazilian favela like this one in Paraisópolis. What had never happened to Isabel was that someone should be so attentive to her own family. “It’s the food, the basic basket, everything. The girl who comes here all the time. She asks if we are sick, if we have a fever, she brings masks, sanitizer gel…” explains, marveling, without taking off her mask, this woman who lives with her daughter-in-law and three grandchildren in one of the biggest favelas in São Paulo.

All of this help is the result of a plan organized not by the authorities, but rather by the powerful effort of Paraisópolis residents to face the most recent challenge in its almost 100 years of history. The coronavirus.

The “girl” Isabel mentions is a long-time neighbor who, with the pandemic, became a street association president. Her primary mission is to visit 50 families in daily rounds. She distributes food, checks if anyone has symptoms of the virus, if they go out to work… She takes help and collects information like the best gossipers to make her neighbors survive this plague and its consequences in one of the most unequal countries in the world.

The 660 street presidents manage to balance people’s needs even in the farthest corner of this steep alley labyrinth. Inequality in Brazil is so brutal that in São Paulo the difference in average life expectancy between the best and the worst neighborhood as 14 years: 71 to 85.

The first battle the favela activists were forced to fight was against the false belief that the poor were safe from the coronavirus. Since the first Brazilians hospitalized were wealthy, those who travel to Madrid or Milan, dine in French restaurants with red wine or are members of exclusive clubs, many of those who may not even dream of this believed they were immune. The false notion that the new disease would be less cruel in tropical countries was also prevalent.

These deceptions, when added to President Jair Bolsonaro’s discourse as he disdained the threat classifying it as a “minor flu”, combined to make a potentially devastating cocktail in Brazil’s favelas. Volunteers immediately set to work with a car and a megaphone to persuade the neighborhood that the threat was real. Unless they acted quickly, the consequences in the favela would be catastrophic. The collapse of hospitals in countries like Italy or Spain on TV sufficed.

The coordinator of the neighborhood music program – an evangelical pastor – and a fireman took turns driving the minibus through the many paved streets that cut through Paraisópolis in an attempt to raise awareness of all these aspects that made this epidemic turn things like going out exclusively for what was strictly necessary and washing your hands frequently as day-to-day life.

A huge challenge in this São Paulo favela, where confinement is a luxury available to very few and where families would like to have money saved for when unforeseen events arise. Informing and raising awareness was the first mission of the veteran activists engaged in a thousand battles.

Ahead of this mammoth effort is a 36-year-old charismatic fellow, Gilson Rodrigues. His official title is that of president of the Paraisópolis Union of Residents and Commerce. In his daily life, he is the person to whom the 75,000 residents turn when they have a problem, the closest to a mayor they know in this favela, one of the most organized in São Paulo and one of the wealthiest in Brazil.

“I have a responsibility. And I strongly believe in setting the example. I try to make few mistakes and quickly correct them,” says this experienced activist who managed to distinguish his favela from the others. Paraisópolis is not known for selling drugs, which occurs there, or the police operations, but rather because it breeds business with a social impact, it has an orchestra and even a ballet (by the way, it is not the only favela with a ballet school). Rodrigues is an obstinate man, who wears casual clothes, but is impeccable. Other poor communities are replicating his initiatives.

He and his team thought of a solution to each of the many problems triggered by the pandemic, which has now officially killed over 145,000 Brazilians and infected more than 4.9 million – figures that should be considered with caution because, as Brazil conducts very few tests, they are probably far below the real numbers. The virus has been more lethal only in the United States and India.

“The SAMU [city ambluance service] doesn’t come to Paraisópolis? We hire ambulances. Do people need to eat? We prepare Maria’s meals. Do people need masks? We start producing them. We found ways for people to overcome this pandemic,” explains Rodrigues in the pavilion that has become the heart and brain of a complex arrangement to soften the blow. After the initial panic, they faced the challenge with imagination and efficiency.

The more than 75,000 residents of this favela in São Paulo and the many others spread across Brazil had it all playing against them when the virus emerged. Places like this are densely populated, with shacks instead of houses, and lack services, often precarious. These are neighborhoods where the government is very little present due to fear or negligence, where the residents would like to have better teachers, more doctors, and fewer police. Obesity and hypertension are common.

“Unfortunately, Paraisópolis and other favelas have been abandoned for a long time. We will turn 99 now. It’s 99 years of abandonment in which public policies were not implemented in order for the inhabitants to develop. Since the government does nothing, we residents are uniting to change this reality,” Rodrigues says.

The chaos that has marked the political management of the epidemic since the first minute in Brazil was added to this chronic neglect. Bolsonaro fired two Health Ministers, sabotaged governors’ efforts, promoted a drug of unproven efficacy, Not caring if the health crisis was worsening, his position was always that an economic collapse would kill more than Covid-19. With good political repercussions, in one month he passed the emergency aid that reaches one-third of the population. Despite the high death toll, he is more popular than ever.

The community leader of Paraisópolis and the activist-entrepreneurs around him sought donations by land, sea, and air. They have opened several crowdfunding lines on the Internet, where they move skillfully, and, as they say, report them on Facebook and Instagram. It worked. The pandemic triggered in Brazil a veritable race to ask and donate. The residents’ union hired doctors and nurses who are on call 24 hours a day, in addition to an ambulance, because those in the public health system do not dare enter the favela.

They managed to get the authorities to provide them with two public schools to set up reception centers where they could quarantine asymptomatic infected people living in precarious housing where isolation is impossible. Doctors from one of the best private hospitals in São Paulo offered consultations by videoconference. They had almost 500 isolated patients.

In August, with the drop in donations and demand, they closed these centers. Other initiatives remain in full swing five months later. The aim was to adjust what they had to the new circumstances. To begin with, their headquarters. Since the day care center for the elderly in the neighborhood was forced to close because of the virus, they converted it into their headquarters. Several social impact companies – a definition on which their founders insist – founded under the umbrella of the residents’ association suddenly found themselves with no contracts or clients. In a matter of days, they began to work to meet their fellow residents’ needs.

Monday. One hour before the start of distribution, the line is forming. The same occurs on Tuesday. It is the first time that Daniele Brasiliana, 34 years old, mother of three children, comes to pick up her packed lunch with hot food for her family. Although she lost her job in a market, she had been finding ways to support her family, but now there is nothing left to eat at home. And here she is. First in line. The Mãos de Maria project, which used to prepare meals for events and schools, now cooks and distributes 5,000 portions a day to neutralize the ghost of hunger.

A well-served dish of rice, beans, meat, and salad. Since the beginning of the crisis, more than 700,000 dishes have been cooked and distributed, but the pace has been reduced because donations have decreased. Another of these companies, Costurando Sonhos, moved from creating its first sustainable fashion collection to recruiting women and sourcing sewing machines to manufacture masks at home. Over 270,000 masks, thanks to 68 seamstresses. Here no one lines up without a mask, yet it is not uncommon to place them only upon reaching the distribution center.

Paraisópolis was a vacant lot intended to accommodate homes for the upper class when, 99 years ago, it began to be inhabited by people who came from far away with nothing but the clothes on their bodies and with no place to live. Those migrants coming from Bahia, Pernambuco, or Ceará – from very poor areas, victims of periodic droughts – reached the São Paulo metropolis in search of work and a decent future. “When I came here there were no houses, only woods, some plantations, and shacks,” recalls Isabel Brito, who works hard caring for others. She came by bus when she was 17. Only then did she learn to read a little.

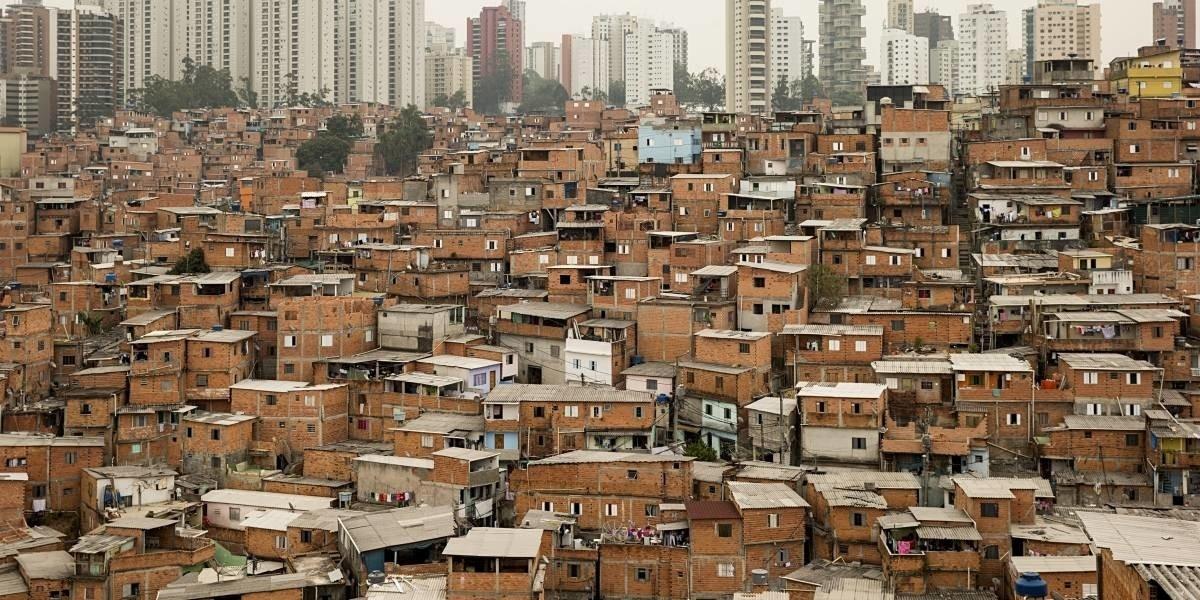

Today, the neighborhood where she lives is one of the places in São Paulo that best illustrates the inequality that corrodes Brazil. Skyscrapers with pools on the terraces -on all floors- rise majestically above fragile exposed brick buildings and zinc roofs grouped disorderly.

The paradox is that this closeness that vividly exposes the abyss that separates the one percent of Brazil’s most privileged from the millions of countrymen living in favelas is precisely one of the reasons why Paraisópolis is one of the country’s most vibrant communities. The supply and demand for labor is two steps away, and this, in a megalopolis of almost 20 million inhabitants with terrible traffic, is of critical significance.

With its community response, Paraisópolis succeeded in minimizing the damage, preventing a major catastrophe, but the blow was harsh. The virus soon showed that it does distinguish between classes, generally in favor of the privileged. Also in Brazil, the pandemic struck the poor and black people harder. In May, the mortality rate by Covid-19 in this favela was less than half the average in São Paulo, according to a study by the Pólis Institute. This fact attracted attention because it differed from similar neighborhoods and made it seem like other more privileged ones, although the study’s authors alerted that the average age in Paraisópolis was lower.

The most recent data make up a diametrically opposed picture. The same academic team proved that by late August the São Paulo average stood at 133 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, but in Paraisópolis it was more than double (293 per 100,000). “Those solidarity measures of mutual support had an impact that was reduced because people continued to go out in search of sustenance and lacked decisive support from the government,” says one of the study’s authors, doctor Jorge Kayano. The specialist is outraged by the fact that the Brazilian public health system, which achieved such good results against HIV, is in the hands of someone like Bolsonaro.

The catastrophe first came in the form of dismissals. While employers were retreating home to continue working remotely with meetings through Zoom, it didn’t take long before most of them were dismissing nannies, drivers, cooks, housekeepers, doormen, etc., who were neighbors but lived in the favela. Another enterprise born from the residents’ activism, known as Favela LinkedIn, launched the ‘Adote uma Diarista’ (Adopt a Day Worker) campaign.

“Many household heads have to pay rent. With the confinement, they had two options: either to stay at home and starve or to go out and look for work and risk becoming infected,” explains Rejane dos Santos, 35, founder of the company that connects employers with the unemployed. It was a success. They intended to help 500 people and collected donations for 1,032. With the progressive return to normality, the program was renamed ‘Contrate uma Diarista’ (Hire a Day Worker).

Both Rejane dos Santos’ enterprise and those that now offer hot meals or sew masks were born as workshops to train neighborhood women, who had a much worse education than they wished, in trades with which they could achieve economic independence and the consequent freedom. These activists and entrepreneurs were able to offer jobs (and new horizons) to their neighbors. As they always say, they are social impact businesses.

Paraisópolis showed its kinder face in a telenovela a few years ago, but it also has a sinister side because, like other favelas, it is under the control of a criminal organization. This drug market is particularly lucrative and valuable to the Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC) for its proximity to a wealthy neighborhood.

Like millions of people, the world of Claudia Regina di Silverio, 48, collapsed at the start of the pandemic. She lost her job because she worked at home taking care of nine children whose mothers had no one to leave them with when going out to work. Until they were fired. Suddenly, those mothers could not pay her, nor did they need her. And her ex-husband continued to fail to pay her two children’s child support. Di Silverio turned to the neighborhood association, as on other occasions. They didn’t have a job for her, but they had a proposal: did she want to be president of her street? That’s how she began to visit 50 families every day.

Monday, shortly after noon. Di Silverio carries two bags packed with hot food dishes as she passes through Harmonia alley. With a mask, hair net and a T-shirt that reads “Stay at home”, she knocks on the door of Natalia, a seven year old girl who now follows her classes using a cell phone. Around here, hardly anyone owns a computer. The girl takes the food for her brother and her father. From there, the president heads to the home of Célia Gomes, a mother of 14 children who, at the age of 40, already has her sixth grandchild on the way.

Before the pandemic she had no decent job; she scoured the garbage for recyclable materials. She is part of the millions of Brazilians who live not knowing if they will have enough for one more day. Unless they go out in the morning in search of food, they and their families will not eat. After the round, Di Silverio returns home to bake cakes, which she then sells. With this, she pays the bills and raises her children while ensuring that her neighbors are protected from the virus and have what they need to endure until the vaccine comes.

Source: El País