RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Human development is progressing in Latin America, albeit at a noticeably lower rate than in the rest of the world and lower than in recent decades. All but three of the region’s countries – Argentina, Venezuela, and Nicaragua, economies immersed in economic and political crises – improved last year in the Human Development Index (HDI, which gathers many variables in all areas), disclosed on Monday by the United Nations.

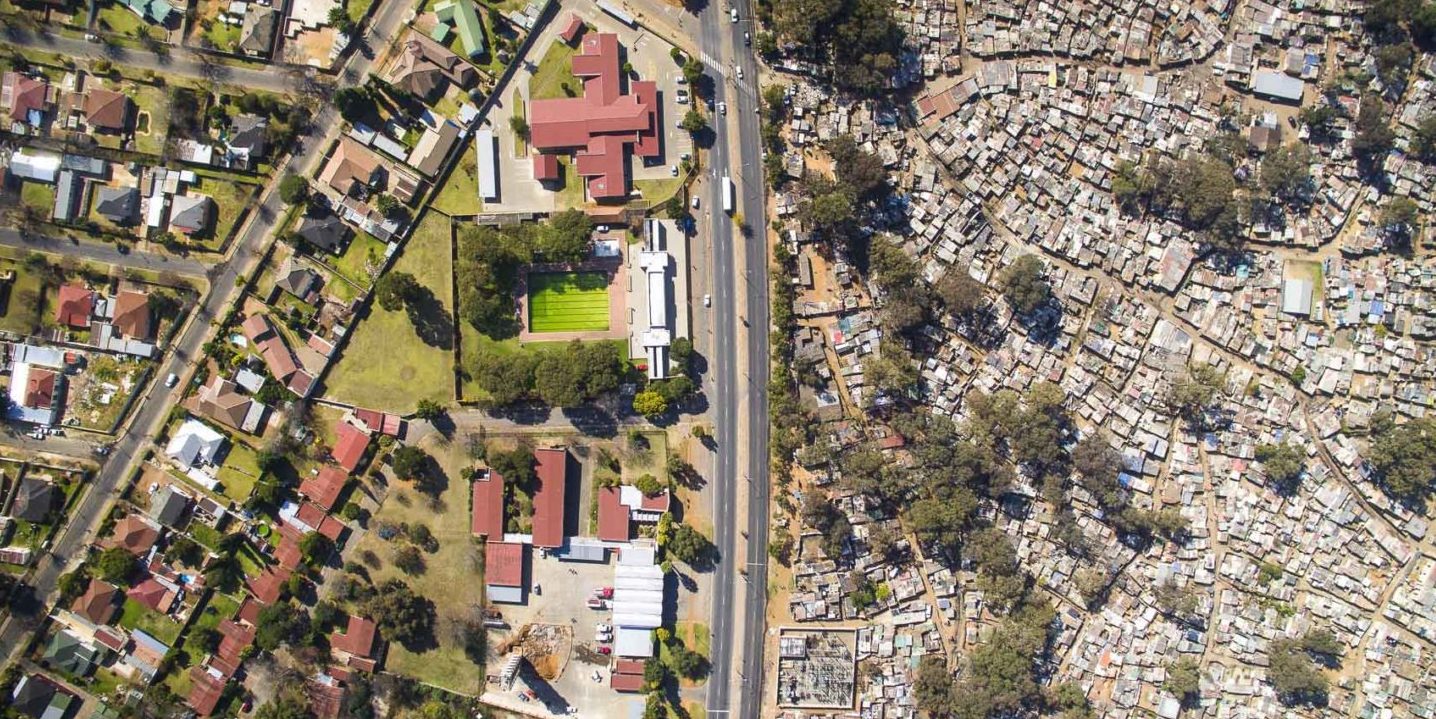

Inequality is particularly cruel in the subcontinent – the most unequal region in the world – and has increased systematically in the measurements of virtually all the countries in the region. The HDI is a formula to measure the population’s well-being, and is far more comprehensive than per capita income: it is not limited to economic factors and includes variables such as life expectancy and quality of education.

“Although inequality indicators have improved in many countries in the region, levels remain very high,” said Pedro Conceição, the report’s director. “There has also been progress in health and education. But income has not kept pace, mainly as of 2014. Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, Chile, Paraguay, and Panama are among the most exemplary cases of how large income disparities reduce social progress.

Brazil, accounting for most of the increase in extreme poverty in the region in the past five years, loses 23 positions in the United Nations rankings when the inequality factor is incorporated. Chile, for decades taken as an example of economic liberalization policies in Latin America and now immersed in its most turbulent social period since the end of Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship, with an uprising against social injustice and the absence of a truly protective state, retreats 14 places; Mexico is down 17; Colombia, 16; and Paraguay and Panama, 14 and 13, respectively. In all these countries, the most common measure of income distribution, the Gini coefficient, exceeds – by far, in the case of Brazil – the world average and that of other developing countries.

In the case of Latin America, the administrator of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and also president of the United Nations Development Group, Achim Steiner, bluntly links the recent wave of social protests in several countries in the region – Chile, Ecuador, and Colombia, among others – to a “widespread feeling of discontent among the population” and to inequality itself.

The Chilean case is perhaps the clearest when the UN data are crossed with the claims of the protesters who took Santiago and other large Chilean cities: in a country where social demands clearly point to the absence (or poor quality) of public services, prosperity – one of the richest nations in the region – is not everything, and income-related disparities and social discrimination weigh heavily on overall well-being.

Inequality monograph

UNDP usually focuses an important part of its annual assessment on the influence of inequality on the index in all regions of the world. This time, however, the emphasis is much greater. The data clearly justifies the reason for the body’s greatest concern: although the global advance of extreme poverty is unquestionable, UNDP experts point out – a point on which Latin America has also failed in the last five years – “the gaps in inequality remain at unacceptable levels”.

In a very high human development country, a 40-year-old from the wealthiest one percent will have a life expectancy between ten and fifteen years longer than someone from the poorest one percent. And while a child born in the year 2000 is 50 percent likely to be in college today, another child born in the same year in a country with low human development (such as Haiti, to name one case in the region) is 83 percent likely to have survived and only three percent likely to be in higher education today.

Further UNDP data corroborate the reasons why the problem of inequality has not ceased to weigh on the scale of concerns of major international organizations: if economic growth follows the pattern set by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in its projections, the number of people in extreme poverty around the world will remain above 550 million – more than the combined population of the United States and Brazil; but if each year the Gini index could be reduced by one percent, 100 million more people would escape extreme famine.

In the case of emerging countries, the problem of inequality lies largely in the state’s inability to redistribute: the initial position is virtually the same as that of advanced economies, but, unlike the latter, taxes and public transfers can barely correct differences in income.

Despite the usual reading of inequality as a mere economic measure, the UN encourages a step forward. “We still have a sense of inequality in the 20th century that is only linked to per capita income,” says Steiner. “But these initial economic inequalities have given rise to a new generation of inequalities: micro inequalities that start from the perception that ‘my child is born in disadvantage’. And this shows a lack of social mobility. In Latin America, this disruption of social ascension is all the more evident.

Except for the cases mentioned above – Argentina, Venezuela and Nicaragua, the evolution of the human development indicator is positive in the region.

With one important reservation: it is the area with the lowest rate of progress since 2010: less than 0.5 percent per year, half that of South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. In contrast, the greatest improvements in 2018 are in Peru, which rises four places, and in Bolivia, which has already joined the group of nations with high economic development and which is by far the country where there has been the greatest improvement in the living conditions of its citizens over the past three decades.

Conceição believes that in both cases, much of the improvement can be ascribed to economic growth. The are only two small pieces of good news, however, in a markedly negative environment due, to the devastating effect of inequality on human development.

Source: El País