RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Racial inequality scholars say that for the fight against discrimination of the black population to produce consistent results, there is a decisive step that we Brazilians have not yet taken: to accept that we are, indeed, racist – either as individuals or as a society.

According to philosopher and jurist Silvio Almeida, president of the Luiz Gama Institute (NGO working for racial equality) and professor at Mackenzie University and the Getúlio Vargas Foundation, when the existence of racism is accepted, the moral obligation to act against it is automatically established:

“Denial is essential for the continuity of racism. It can only work, and be reproduced without embarrassment, when it is denied, naturalized, incorporated into our daily lives as something normal. If racism is not recognized, it is as if the problem does not exist and no change is required. Awareness, therefore, is a key starting point.”

As an example of denial, the attorney and sociologist José Vicente, dean of the Zumbi dos Palmares College and director of the Afro-Brazilian Society for Sociocultural Development (AFROBRAS), mentions a glaring contradictory behavior: the inflamed outrage shown by Brazilians on social media and even in street protests, following a worldwide anti-racist wave, in reaction to the murder of the black American security guard George Floyd, asphyxiated by a white police officer in Minneapolis in May.

The outrage seems contradictory because Brazilians watch on television and read in the newspaper, almost daily, crimes committed in their own environment as racist and cruel as what happened in the United States, but they do not react with the same commotion – if at all.

“Brazilians understand that there is racial hatred out there, not here. They believe that in Brazil we live in a racial democracy, mixed, happy and free from conflict. That is the perversity of our racism. It was built in such a skillful way that Brazilians reach the point of not wanting or not being able to see the glaring reality right before their eyes.”

To show that the effective fight against racism hinges on the end of denial, attorney Humberto Adami, who chairs the Brazilian Bar Association’s Commission on the Truth of Black Slavery, also resorts to racial crime in the United States. Adami recalls that in Brazil, news channels have given Floyd’s murder a great deal of scope and have called in their most renowned journalists to make reviews on debate shows – all white journalists.

“The most attentive viewers to the racial issue reacted on the spot. It was only then that broadcasters realized the absurdity of the situation and, in order to retract, called black journalists to the debate on racism. Individuals and institutions are generally absolutely certain that they are not racist, yet their attitudes ultimately show the opposite. If a society is racist, then its TV, its university, its police, its courts, etc. will also be racist. These TV events show how black people are at a disadvantage when denial prevails and how everything changes when we become aware that we are racist.”

Common sense tends to understand racism in a simplistic way, limiting it to those situations where a black is banned from entering the club, prevented from taking the social elevator, searched when leaving the store, or insulted with derogatory words that refer to the color of their skin. Such cases, of course, are racist and punishable, but prejudice extends far beyond that.

Racism also shows in ways that may be less blatant but have more devastating impacts on the lives of black people. In any aspect of life, blacks (“pretos”) and mixed-race (“pardos”) are officially classified as blacks “negros” and are always at a distinct disadvantage when compared to whites.

In Brazil, being black means being poorer than whites, being less schooled, receiving a lower wage, being rejected by the labor market more often, having fewer opportunities for professional and social ascension, finding it difficult to reach the top of public power and the private sector’s leadership positions, being among the main occupants of underemployment, having less access to health services, being a more common victim of urban violence, having more chances to go to prison, dying earlier.

When denial prevails, this reality is interpreted as a natural and inevitable consequence of social inequalities in Brazil, and one cannot understand that its true cause is racism. That is why deniers reject racial policies such as the demarcation of ‘quilombola’ lands (Afro-Brazilian settlement) and the creation of quotas in universities and public bids.

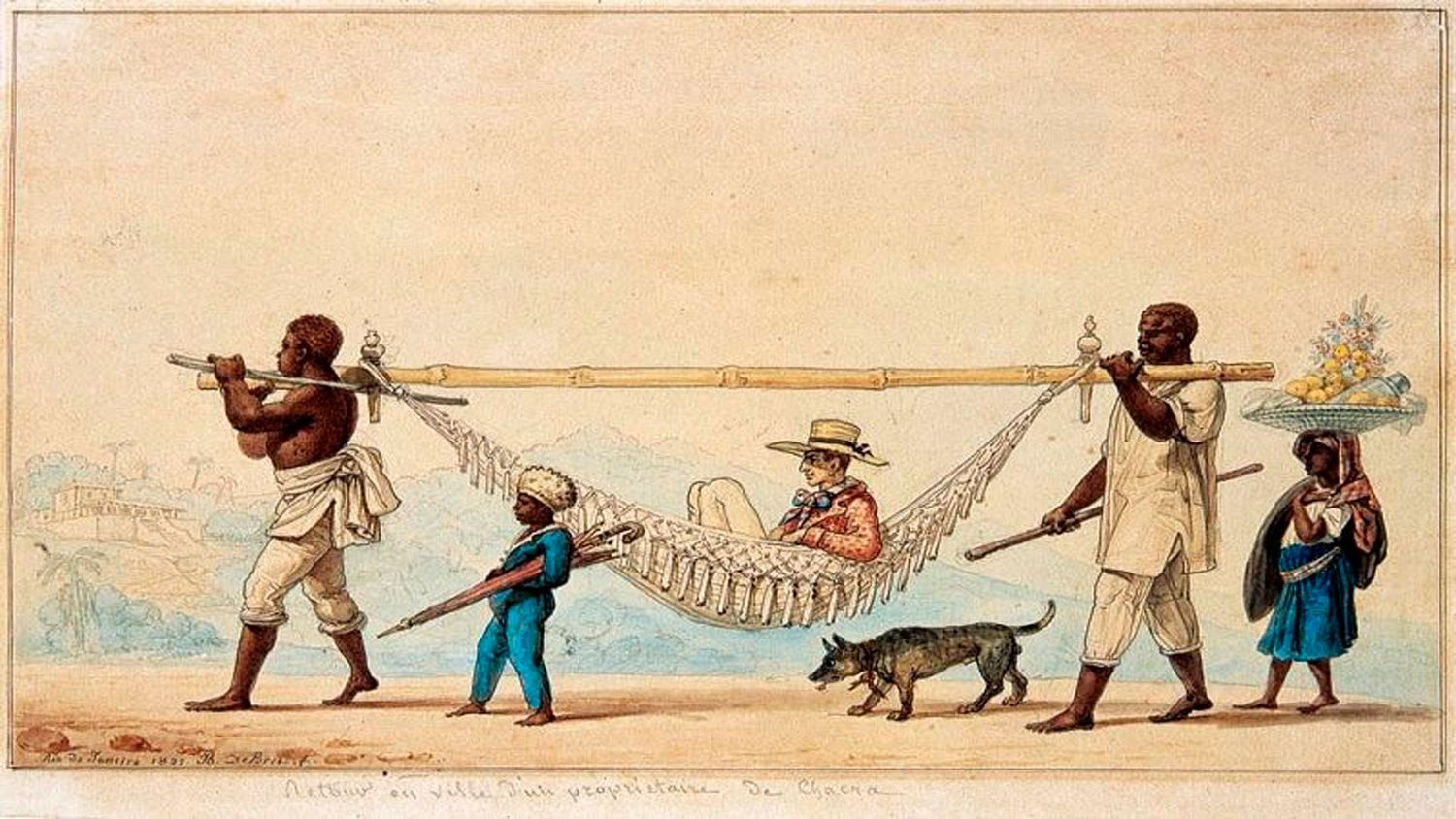

According to scholars on the subject, the foundations of Brazilian racism lie in the almost four centuries that African slavery prevailed here. During the colonial and imperial periods, it was slavery that was responsible for positioning blacks and whites in different worlds. With the signing of the so-called Golden Law in 1888, whites created less explicit mechanisms than senzalas (slave camps) and shackles to keep blacks in a place of subordination.

Black-skinned people were able to abandon servitude but were not given the instruments needed to tackle life on their own with dignity. They were not granted land or schools, despite the fact that legislators had submitted bills to that end. Nor did plans to compensate them for their years of captivity prosper. They ultimately restricted their work. For coffee plantations and the initial industries in Brazil, the Government preferred to encourage the immigration of workers from Europe and Asia.

Professor Silvio Almeida says that, from slavery to the current format, racism has been metamorphosing in the course of time, able to adapt to changes in society.

“In the early 20th century, for instance, scientific racism was fashionable. In academic circles, there was this notion that it was the black man who produced the disorder and crises that Brazil lived in the First Republic. Scientific racism thus legitimized the use of violence against this population. In parallel, it was believed that miscegenation would be beneficial to the country because strong white blood would prevail over weak black blood and the population would be whitened. That destabilizing group would eventually be eliminated. To put it more bluntly: eugenics. In the 1930s, the prevailing discourse was that of racial democracy. Brazil would be a plural country, with whites, blacks and indigenous living in harmony, all important, as long as each race remained in its place. It was no longer a question of eliminating blacks, but of keeping them in a subordinate position.”

According to dean José Vicente, nowadays racism is “disfigured, multifaceted and extremely slick.”

“The master’s mansion and the ‘senzala’ are still there, only now with a modern twist. Racism has been muted and has improved to the point that it has gained a subtlety that often is only detected in detail. Consider the 2003 law that made it compulsory to teach the history of Africa and black culture in schools. It is an important and necessary content, mainly because 55 percent of the Brazilian population is black. However, only a small proportion of schools obey the law. Principals and teachers will find a thousand arguments to justify non-compliance and say that this has nothing to do with racism. Many are racist because of ignorance, unawareness, but others are racist in an enlightened, conscious way.”

In Brazil, there exists what scholars call structural racism. Racism is structural because it stands as the foundation on which political, economic and social relations are built in the country. People and institutions are shaped, sometimes unconsciously, to consider it normal for whites and blacks to occupy different places. That is why hardly anyone is shocked by so many blacks murdered on the outskirts of cities and so few blacks present in governments and courts.

The concept of structural racism shows that there is a motion, within society as a whole, to take from the blacks and give to the whites. Thus, while not ignoring personal responsibilities, occasional racist actions present themselves as smaller demonstrations of a behavior that is broader and more collective. Just like racism, in Brazil machismo is also structural.

“Do you know how many people are imprisoned in Brazil today for racism?” – asks attorney Humberto Adami. “None. This is another indication of our structural racism. We have laws that provide punishment for crimes of racism and racial insult, but they are not enforced. And they’re not enforced because there’s simply no demand from society.”

“To be black in Brazil is to know that you will get differentiated treatment from the world,” says dean José Vicente. “The most mundane rights will not be available to you in full, and you will always be forced to demand them more intensively and even fight for them. Not even the right to come and go can be enjoyed peacefully. Every time a black son leaves home to go to school or to the movies, a black father will need to remind him of survival strategies: don’t wear a hat or cap, keep your clothes straight, take your ID with you and even your worker’s record book, lower your head and raise your hands if you are approached by the police. The white son, on the other hand, can wear his clothes all torn and be sure he will not be harassed. Being black means being in a permanent struggle in public and even private environments.”

Senator Paulo Paim, ex-vice president of the CPI (Parliamentary Committee of Inquiry) for the Assassination of Black Youths and the legislator who drafted the bill that gave rise to the Statute of Racial Equality (Law 12.288, 2010), says that since racism is structural, no black in Brazil can escape discrimination.

“As with all Blacks, I can mention a dozen situations of racism that I have experienced. If a black person, regardless of social position, says that he has never experienced an incident of discrimination in life, it is because it is such a deep wound that he/she chooses to remain silent so as not to feel the pain again.”

According to experts, racist people should be punished. However, more effective than just fighting individual crimes is overthrowing the structures of society that breed racism and racist people.

“First and foremost, we must remove this lens that makes people perceive inequality and racism as natural,” says Professor Silvio Almeida. “This requires changing education, the school, to nurture the desire for equality, diversity, and integration in the minds and hearts of individuals. It also requires changing the media’s approach, from soap operas to newspapers. When the shows interview black people only on May 13th [anniversary of the Golden Law] or November 20th [Black Awareness Day] or so that they only recount their personal tragedies, they are enhancing the production of an imaginary scene that binds the black man directly to his racial belonging. In the absence of this, people change their own behavior and also induce changes in politics, economics, law, and culture.”

According to him, it is not an easy change to make, since racism ensures whites a privileged position in society. But there are arguments to persuade them to engage in this change and give up the benefits that the racist wheels of society have historically ensured them.

“There can be no democracy in a racist society. A racist society is systemically authoritarian because it needs to use force and violence to reject the fair demands of the majority and serve the minority. Maintaining inequality, poverty, and low political representation requires systemic violence, which will then be used against whites as well. Moreover, if the majority of society is poor, violated and humiliated all the time, this society cannot be healthy. It is a terrible place for anyone to live, including whites. Commitment to the anti-racist struggle means commitment to democracy, to sound economic development and to humanity.”

Source: El País