RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Averse to risk, Joseph built an empire that he tries to pass on to his children. Discreetly, like everything in his life.

Full name: Joseph Yacoub Safra

Occupation: Banker

Place of Birth: Beirut, Lebanon

Year of Birth: 1938

Fortune: US$20.4 billion

Who is Joseph Safra

The wealthiest man in Brazil was not born here. Banker Joseph Safra was brought into this world in Beirut, Lebanon, and left his native country to pursue a life in Latin America, following his family’s trade.

Safra is the descendant of a long bloodline of bankers who financed and exchanged currency and gold among merchants from Europe, the Ottoman Empire, Africa, and Asia.

Joseph soon started working at his father’s bank, who came to São Paulo to found Safra Bank, today the 4th largest private financial institution in the country.

Safra’s success is rooted in its extreme financial conservatism: following his father’s teachings, the banker hates risks and maintains the liquidity required for the bank to be recognized for this very reason.

Slowly and consistently, Safra has accumulated wealth while always planning for the very long term. The results can be assessed in the present.

His fortune exceeds that of any other Brazilian. But Safra also stands out in yet another battle of giants: he is the world’s wealthiest banker, with a net worth of US$20.4 billion.

At 82, Safra left the spotlight, leaving the bank to his children. Currently, the banker spends more time in his 11,000 m² mansion in the Morumbi district of São Paulo.

Away from the financial sector, the surname Safra is also recognized in the philanthropic environment through donations to hospitals, museums, and the Jewish community.

Origins and family

Joseph Safra was born in 1938 in Beirut, Lebanon, into a Jewish family with over a century of experience in banking. His origins are also found in the city of Aleppo, Syria, where his father Jacob Safra was born.

Long before he considered having children and moving to Brazil, Jacob lived in the traditional city of the Syrian north, the convergence point of the three continents, and the route of the caravans that controlled the land trade between the West and the East.

At the age of 23, Jacob was sent by his uncle Ezra Safra to Beirut, Lebanon, to open a branch of Safra Frères & Cie, which belonged to his family since the mid-19th century. The house operated as a bank, granting loans and exchanging gold and coins from Asian, European, and African countries.

In Lebanon, Jacob founded a new bank in 1920. This time under his name: Jacob E. Safra Bank. He expanded his family’s activities in the Middle East, becoming famous for rapidly converting values among several currencies for his clients.

Jacob Safra also established his family in the city, after marrying Ester Teira Safra and having nine children. Among them, Joseph was born.

The establishment of the state of Israel and the beginning of the new country’s conflicts with its neighbors led to a more unstable environment for Jews in the Middle East. Although Lebanon remained reasonably safe for Jews in the region, Jacob Safra decided to leave the country and head for Latin America.

“My father imagined that a 3rd great war would not be long in coming and began to look for a quieter country to live in. He chose Brazil,” said Safra.

In 1952, Jacob Safra settled in São Paulo, a city that was experiencing growth and political stability, in addition to housing a sizeable Syrian-Lebanese colony.

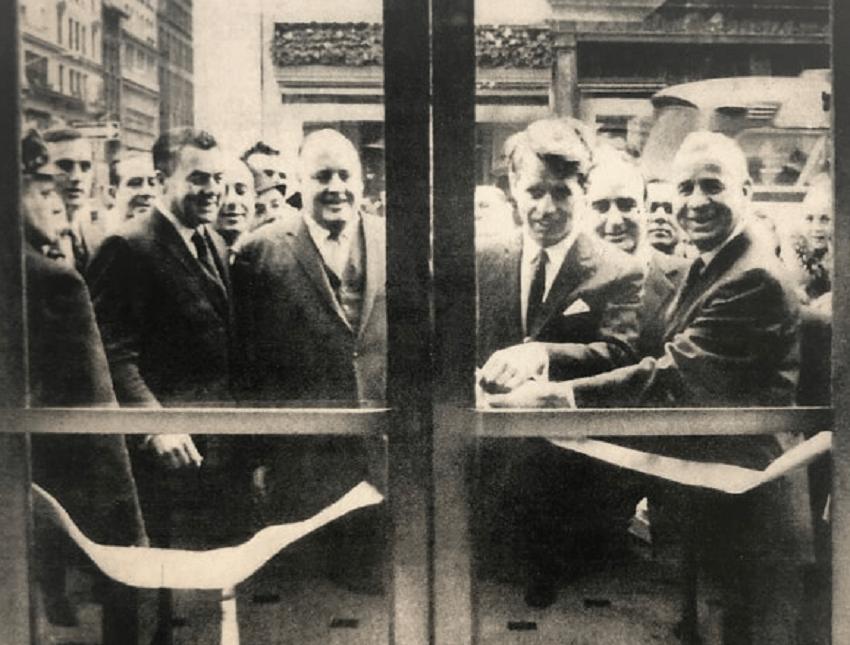

But the Safra family did not come as a whole to the São Paulo capital. Joseph left to complete his studies in England. After that, he moved to the United States to work for Bank of America. Only in 1962, after a stint in Argentina, did he join his father and brothers in Brazil to run the financial institution founded five years earlier.

Working in a bank was nothing new for Joseph – or José, as he came to be known in Brazil. As a teenager, he would only follow his father and work as a messenger. But his first venture into the investment world was a disaster – and a great learning experience.

Believing in the appreciation of the Egyptian currency, Joseph acquired a value equivalent to US$300. It failed, and he lost all his money. The banker tells that he was unable to sleep properly for almost a month, thinking about what he had done.

From that experience at 17, he would carry a lesson in life: risk was not his area.

Banker’s life

After his father’s death in 1963, the Safra brothers continued to manage the financial institution. However, it still did not fully enjoy São Paulo’s trust.

Making use of their experience of over a century as bankers, the Safra family brought techniques already developed in more sophisticated financial markets to Brazil, such as the Middle East, but still strange to the national market.

Among the innovations, the Safra introduced the use of the bill of exchange as a means of financing operations and provided yield to the money in their accounts, the beginning of the interest-bearing account – today used by several banks and digital banks.

Despite the initial skepticism, Safra Bank’s stability and conservatism – officially founded in 1967 under the name Banco de Santos – attracted part of São Paulo’s wealth and earned the reputation of being the “bank of bankers.”

For Joseph, preserving Safra’s reputation and solidity is the key to his business.

With the success of their operations, the Safra began to buy other financial institutions. In 1972, with the acquisition of Banco das Indústrias (Industrial Bank), the name Safra Bank started to be officially used.

Jealousy of its employees

The bank was led by two of Jacob’s three sons who founded the business: Joseph and Moise.

His older brother, Edmond, was sent to Geneva, Switzerland, by his father, and then to New York, where he became the most public figure in the Safra family. In the USA, Edmond founded the successful Trade Development Bank and the Republic National Bank of New York.

In Brazil, Joseph pursued the conservative and extremely discreet tradition of those bearing the Safra surname. Around himself and his family, the banker erected higher walls than those surrounding his 100+ bedroom mansion in the Morumbi district of São Paulo.

Throughout his life, Joseph granted very few interviews and never attended the social columns, ever filled with billionaires and their eccentricities.

The available data on the Safra group comes from official releases, balance statements, and acquisitions – as well as few, albeit significant, scandals.

Joseph has consistently controlled Safra meticulously. His management style involves much study of business risks and a unique commercial acumen.

Stories told by those who worked alongside “Seu José” show an attentive but often severe bank owner.

Among the “legends” about Joseph are calls to his executives on Sunday night, pressuring them to close exchange operations that, according to him, would not allow him to sleep peacefully.

A jest spreads in the business world that the banker only lends money to those who do not need it: he would ask for so much collateral on the viability of businesses that no one could persuade him.

In the market, the tale that José used to present his executives’ wives with jewelry when their marriages were in crisis is also well-known. The treat was a way of apologizing for the many extra hours that the banker would have their husbands work.

Safra always nurtured a close relationship with his employees, who were free to call him by his first name and walk into his living room. Lunchtime was the moment José took to show who his favorite executives and employees were – which sparked jealousy outbursts among the unselected.

And the feeling was mutual. When one of his executives left Safra after being invited by a competitor, José was furious. In exchange, he hired his rival’s whole team. “I don’t like having employees taken from my bank. I’m jealous,” he said. In the end, the bankers made amends.

Betting on privatization

In the 1980s, with galloping inflation ravaging Brazil, Joseph seized the opportunity to profit from an unusual application: the savings account.

The banker noted that May 1988 would have five weekends and that no other conservative investment would beat the yield from that month’s savings.

Safra deposited 21 billion cruzados – approximately US$125 million – in savings accounts of the Banco Nacional de Crédito Cooperativo (National Bank of Cooperative Credit – BNCC) and the Caixa (Savings Bank). The banks paid the agreed yield but changed the rules to restrict high deposits.

But Joseph’s gambles were not always accurate.

One of his worst occurred during the wave of privatizations of Brazilian telecommunications in the late 1990s. Safra teamed up with BellSouth and founded BCP, the first company to be allowed to operate a spectrum of the cell phone network, thereby shattering the monopoly of Telebras subsidiaries.

The BCP’s early years were of commercial success. The company became the second largest in the sector, operating in São Paulo, Rio Grande do Norte, Ceará, Alagoas, Pernambuco, Paraíba, and Piauí.

But the financial results failed to keep up with the good initial result. The company began to run in the red, accumulating US$1.5 billion in debt. In 2002, the BCP defaulted on its creditors for US$375 million.

Likewise, the BCP lost the technological battle. The company invested in the TDMA system, while the cell phone market would be taken over by GSM and its SIM cards.

In 2003, the BCP was sold for US$650 million to the Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim’s group, Claro’s controller, who had invested in the migration of TDMA to GSM and saw in the BCP an opportunity to penetrate the São Paulo market. The Safra brothers did not get a cent from this operation.

Jacob’s sons

The Safra’s low-profile intimate life has seldom made the headlines. But in the late 1990s, a dispute between the family’s heirs eventually ruptured domestic borders.

Edmond, Joseph’s best-known brother, was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. The physical restrictions imposed by the condition prompted him to expedite an old plan to dispose of his businesses. Unbeknownst to Joseph and Moise, Edmond sold the jewels of his estate to competitors in the market, ending the concept of retaining assets within the family.

But the troubles within the family effectively began with Latin America’s debt crisis. In 1983, Edmond was forced to sell the Trade Development Bank to American Express for US$550 million, but the deal failed to materialize as agreed.

Banned from repurchasing the bank, Edmond launched a competitor: the Safra Republic Holdings. The “tease” prompted a global campaign by Amex against the banker, which would have spread false news about Edmond’s connection with the mafia, cocaine cartels, and other controversies.

The dispute only ended in 1989, when American Express publicly apologized and donated US$8 million to an institution supported by Edmond.

Years later, it was Edmond’s turn to sell the Republic, a bank deemed so secure that it held gold reserves from competitors such as Citi, in addition to being one of those behind the shaping of the international price of metal.

The Republic was a powerhouse in New York retail. But in 1999, Edmond discarded the bank, and the closing of the deal further widened the gap between Edmond and his wife Lily and Joseph.

The brothers’ estrangement came to a tragic end. In December that same year, an arson killed Edmond in his apartment in Monaco. A nurse was sentenced to ten years in prison after confessing to starting the fire to save the Safra and secure financial compensation.

At the time, Joseph was beginning to outline the succession of Banco Safra in Brazil and wanted to acquire his brother Moise’s share. The rejection of the deal led José to take one of the most considerable risks of his life: cannibalism in his empire.

In 2004, Joseph created the J. Safra bank, headquartered across the street from the iconic Safra Bank building at 2,100 Paulista Avenue. The business was handed over to his son Alberto, 24 years old at the time.

The institution attracted customers and executives who worked with the original Safra, thereby draining Moise’s wealth. While Joseph was losing money at the Safra Bank, the banker was making money at J.Safra, across the street.

In 2006, Moise gave up the battle and agreed to sell his share in the Safra for an undisclosed amount. Joseph was then able to keep the family estate for his four children, cutting off his nephews and his brother from the business, who would pass away in 2014.

J.Safra Bank

Crisis, pyramid and the forest

Joseph planned to complete his succession in 2008, handing Safra over to his three male sons. But the global crisis and the liquidity risks in the international banking system hindered his plans. His sons were still very young and older customers – and wealthier ones – could have doubts about Safra’s solidity.

Amid the crisis that swept giants out of the market and bankrupted banks until then considered ‘too large to break,’ Joseph pressured his executives to ensure liquidity. He wanted to be able to pay all customers who needed to make withdrawals, even in an unlikely scenario where they would all withdraw on the same day.

But if Joseph managed to control the liquidity risk, he failed to prevent one of the Safra’s greatest scandals, which would undermine the bank’s credibility.

As the bubble burst in the US, so did the criminal scheme played by US banker Bernard Madoff: a financial pyramid that handled over US$65 billion. The scammer had several Jewish families among his clients. The trouble was that his products were distributed by Safra as a “conservative investment.”

The information that Safra’s customers had more than US$300 million invested in Madoff’s pyramid and that the money could be lost was spreading in the market.

The crisis in Safra’s image was compounded by Aracruz Celulose’s billion-dollar loss after an investment in derivatives. The company, which reported losses of US$2 billion, had Joseph and Moise among its shareholders, each with approximately seven percent of the shares.

Again, the name Safra featured on newspaper headlines associated with a risky investment, even if this time, the family bank was not involved.

But Aracruz was not a bad investment for Joseph. Far from it. He bought the company for about US$35 million in 1988 and sold it to the Votorantim Group for US$570 million in 2009. The company is now part of the Suzano Group, after being renamed Fibria.

But a positive investment result was not the most critical thing for Joseph.

For the banker, the main goal was to comply with his father’s teachings, which gave rise to the motto regarding the bank’s solidity: having the name associated with risk is fatal for one’s business model. Safra should be the bank where a customer leaves his or her money, knowing that it will be there whenever he or she needs it.

The next decade would add further damage to Joseph Safra’s image. In 2015 alone, the surname Safra was mentioned in Operation Zelotes, SwissLeaks, and the client list of former Minister Antônio Palocci’s consulting firm, which would be a target of the Lava Jato operation.

The following year, the Zelotes would drop the lawsuit against Joseph. But the banker is still weighed down by the accusations of slush fund payments made by Palocci in his award-winning denunciation.

The same plague in the third harvest (Safra=harvest)

The global crisis delayed but did not cancel Safra’s succession plans. Time weighed on Joseph, suffering from the advancing Parkinson’s disease, the same illness that affected two of his most notorious brothers.

In his initial strategy, Jacob, his firstborn, would take command of international operations based in Geneva, while Alberto would lead the commercial bank focused on medium-sized companies, and the youngest, David, would be in charge of the investment bank.

The solution would not last long. After an internal dispute over the bank’s future and management, Alberto left Safra in October 2019 to found ASA Bank, taking with him former Safra president Rossano Maranhão and vice president Eduardo Sosa.

Despite the friendly announcements published after Alberto’s departure, the market noticed the resemblance with the releases during the turbulent dispute between Joseph and his brother Moise for control of the bank. In August 2019, Veja published that the brothers Jacob and Alberto had fought inside the bank, in front of their employees.

The battle between the brothers took place amid a change in Safra’s business model, which came closer to retail, with the launch of the SafraPay machine and the SafraWallet digital wallet. The move was radical for a bank that built its image in connection with the corporate market and the vast fortunes.

In addition to the change of command in Brazil, Joseph, his sons, and Safra also surprised the world with major acquisitions.

In 2012, following the end of the global financial crisis, Safra announced the purchase of Swiss bank Sarasin for US$1.1 billion. The acquisition added a robust US$107 billion customer portfolio to the bank, spread across Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, doubling Safra’s assets in escrow.

With the purchase, the bank internalized the Dutch Rabobank’s private banking portfolio, the financial institution that longest sustained the AAA rating after the 2008 crisis erupted.

Joseph Safra also made two major real estate acquisitions, buying an office building on New York’s famous Madison Avenue for US$285 million and the iconic Gherkin building in London for about US$1.15 billion.

Joseph’s appetite for purchases also included bananas. More specifically, Chiquita, one of the world’s largest banana producers. The US$1.25 billion offer, made in partnership with Cutrale, a leader in orange production in Brazil, helped Safra outperform Irish Fyffes in the dispute.

Art and Philanthropy

The surname Safra is well known in the world of philanthropy. The family shares part of its fortune in initiatives in medicine, the arts, and within the Jewish community.

Joseph is one of the leading donors to São Paulo’s Albert Einstein and Sírio Libanês Hospitals, as well as supporting charitable associations such as the Dorina Nowill Foundation for the Blind, GRAAC, the Association for Children and Adolescents with Cancer, the Association for Assistance to Handicapped Children, APAE and Casa HOPE.

In culture, the banker, through the J. Safra Institute, acquired and donated sculptures by Auguste Rodin, Aristide Maillol, and Camille Claude to the São Paulo Pinacoteca. The institute also sponsors Brazilian artists’ exhibits and events.

Joseph Safra also donates to Jewish schools and synagogues, as well as sponsoring a book that recovers the roots of Jewish families who left the Middle East to settle in Brazil. Safra acquired and donated to the Israeli government the original manuscript of Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, on display in a museum in Jerusalem.

Source: Infomoney