RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – “Nikkeis protest against the president’s speech,” reads the headline of a page in the latest edition of the Nippak newspaper, which reached the newsstands of the Liberdade neighborhood in São Paulo on Thursday, January 23rd. Under this headline, there were two articles by community members criticizing Jair Bolsonaro.

Despite what the headline suggests, the reactions of Nikkei (Japanese or descendants living outside Japan) to the president’s latest statement perceived as prejudiced against them were sparse. This time the target was journalist Thaís Oyama, author of the book “Tormenta”, on the first year of Bolsonaro’s administration.

When asked by journalists on January 16th about a passage in the book, he fired at the press and said: “This is the book by that Japanese woman, whom I don’t know what is doing in Brazil, and is now doing this against the government”.

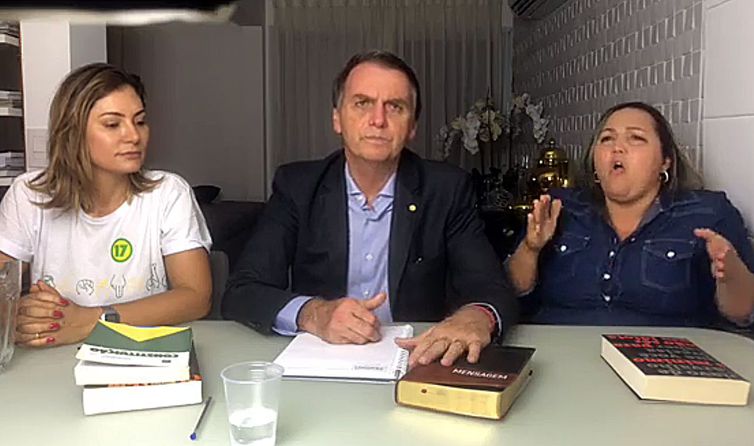

On the same day, during a live broadcast on social media, he again referred to the reporter with annoyance: “Back in Japan she would starve to death in journalism, writing a book”. Thaís is Brazilian, born in Mogi das Cruzes (SP), and the granddaughter of Japanese.

For scholars on the subject, community members and attorneys interviewed by Folha de S.Paulo, Bolsonaro’s statements about the author embody racism and xenophobia and are added to other instances in which the president resorted to stereotypes and made remarks on the ethnic group’s physical features.

According to them, the statements could trigger the opening of a criminal investigation, although the issue is controversial. Ultimately, the case could be classified as a racial insult (when one insults another based on race, color, ethnicity, religion or origin). However, no inquiry has been opened into the case.

Thaís has herself chosen not to fan the polemics flames. She said initially that she would not comment on the attacks and then said she was actually flattered. To Folha, she reiterated her reasoning: “I was actually pleased because if the attempt was to disqualify the book, the statement proved that he had no sound argument to criticize it”.

The journalist says that many people reported perceiving prejudice in Bolsonaro’s statements in the messages of support she received. “It saddened me to learn that some Nikkei felt insulted,” she said.

The Japanese Embassy in Brazil and the Consulate in São Paulo said they have no comments on the matter. With the exception of occasional complaints on social media, the silence of community spokespersons has been the rule.

Since his election, Bolsonaro has engaged in at least five statements or conducts deemed offensive by a number of Japanese.

In May, the president issued two sentences associating the Asian country and its inhabitants to miniatures. While posing with a foreign Asian boy in Manaus, Bolsonaro made a gesture with his fingers and asked: “Everything tiny there?”.

Nine days later, when speaking about the welfare reform at an event in Petrolina (PE), he repeated the comparison: “If it’s a Japanese reform, he [Paulo Guedes, Minister of Economy] will leave. Everything there is a miniature”.

Members of the Japanese community consider the statements far from being mere jokes, they are just as serious as other of Bolsonaro’s statements directed at groups such as Indians, quilombolas (Afro-Brazilian resident of quilombo settlements), women, LGBTs and refugees.

Last Thursday, January 23rd, the Chief Executive said that the Indians are “evolving” and becoming “human beings just like us”. The APIB (Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil) has announced that it will take him to court for racism.

Constitutional law professor Rubens Glezer believes that the range of statements suggests a broader scenario of prejudice to freedoms and individual rights. “The sum of small actions creates a context and an environment that is hostile to certain groups,” says the professor of the Law School of São Paulo.

According to Kiyoshi Harada, author of one of the articles published in the Nippak newspaper, the president’s reactions to Oyama’s book suggest that the group is not welcome in Brazil. He, who is the son of immigrants, claims to have felt affected by speech.

“Whatever the extrapolation of [the journalist’s] freedom of expression, such harsh and prejudiced speech is unwarranted. To refer to her as ‘that Japanese woman’ is derogatory”.

Harada further recalls Bolsonaro’s criticism of Japanese cuisine in October when the president visited the country and hinted that the local cuisine is all about fish. He barely ate the options of an official banquet and posted a photo preparing instant noodles at the hotel.

“He may not have liked it, but it’s not appropriate for a head of state to say such things,” says the attorney.

In 2017, while still a federal deputy, Bolsonaro mentioned the Japanese community in the same lecture in which he attacked the quilombolas – and for which he was judged in the STF (Federal Supreme Court) in 2018. The court rejected a complaint from the PGR (Office of the Prosecutor General) on charges of racism.

In his speech, he criticized the Bolsa Família (“Family Grant”) program when he said, amid applause from the audience: “Has anyone ever seen a Japanese begging around? Because this is race that knows shame”.

According to the historian Rogério Dezem, the statement is imbued with the so-called “myth of the model minority”. The concept, countered by activists who fight against discrimination, involves the notion that the Japanese would necessarily have to be scholarly, balanced, hard-working and honest.

Generalization implies assuming that there are groups that are superior to others in the human race and is seen by many descendants as an instrument of pressure to adapt to an alleged pattern.

“It is worth remembering that Bolsonaro spent much of his childhood and adolescence in the Vale do Ribeira in São Paulo, a region that plays an important role in the history of Japanese immigration. His statement reflects a common perception among a large part of the Brazilian population,” says Dezem.

“These clichés are used when they are convenient. He praises one minority to diminish others,” says sociology student Gabriela Shimabuko, founder of the Perigo Amarelo (“Yellow Danger”) group, which includes Asian descendants and denounces cases of prejudice.

In her view, Bolsonaro has repeatedly been racist towards Orientals and their descendants. “It’s such a nonsense that by 2020 you wouldn’t expect people to say it. But we grow up hearing it.”

The Japanese community in Brazil is the largest outside Japan, with approximately two million descendants. The majority (some 1.2 million, according to the consulate) are located in the state of São Paulo, a part of which is already in its sixth generation. The peak of migration occurred between 1925 and 1935.

In Congress, the president’s remarks on the author of the book were supported by Deputy Bia Kicis. On social media, she complained: “The inconsistency of the press: to call a Federal Police (PF) agent a ‘Federal Jap’ you can’t, right?

Deputy Marcelo Calero says that his speech about Oyama “is the most serious attack that Bolsonaro has ever made on a Brazilian citizen”. He claims he intends to take legal action.

Kim Kataguiri (DEM-SP), who in his profiles defines himself as “the Japanese MBL (Free Brazil Movement),” did not wish to voice his opinion. When asked, he said it is not worth “commenting on all the nonsense the president says”, because this “only increases the repercussions and causes him no embarrassment”.

Rafael Mafei, professor at USP’s Law School, described Bolsonaro’s statements as “ostensibly discriminatory”. “Calling her Japanese is a way to eliminate a person’s identity. It’s a clearly xenophobic type of discrimination,” he said.

From a legal perspective, Bolsonaro could be held accountable in the civil sphere if there were a complaint from the Federal Prosecutor’s Office, the Public Defender’s Office, some social organization or Thaís Oyama herself, claiming compensation for collective or individual moral damage.

A number of legal professionals also see grounds for an inquiry in the criminal sphere. “It fits into discrimination or insult based on origin or ethnicity,” says Mafei.

Glezer points out that there is a debate on what is private and what is part of the civil service of the Planalto’s incumbent under Bolsonaro.

“Is a live broadcast an official statement? Is his tweeting to be regulated as an official communication account?” he asks. Since he is granted immunity, he may only be sued for acts relating to the exercise of his duties.

According to federal Deputy Janaina Paschoal, who as an attorney was one of the authors of Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment petition, Bolsonaro’s statements about Oyama fall into the category of exercise of freedom of expression and do not point to an impeachable “crime of responsibility”.

“I don’t see elements either for an inquiry or for impeachment,” says the former professor of criminal law at USP. “I see that, like many other of the president’s demonstrations, it was very rude. But that doesn’t come into the criminal sphere.”

The Federal Prosecutor’s Office, which has the power to demand explanations from the president or to bring legal proceedings, reported that no proceedings have been opened on the issue and that it has not been petitioned by citizens to act.

When asked about potential actions, the Office of the Prosecutor General says that “it is no use taking positions or demonstrating”.

Journalist Thaís Oyama told Folha that she does not intend to take legal action. “I know that the Japanese don’t like trouble. If I wanted to please them, I don’t think building a case around it would be the best way.”

The presidency reported it would not comment on the case.