By Elaine Patrícia Cruz

Photos by Evandro Teixeira

Editing by Graça Adjuto

In 1973, photojournalist Evandro Teixeira was sent by Jornal do Brasil (JB) to cover the military coup in Chile.

Accompanied by reporter Paulo César de Araújo, Teixeira left for Chile on September 12, the day after the coup that led to the death of then-president Salvador Allende.

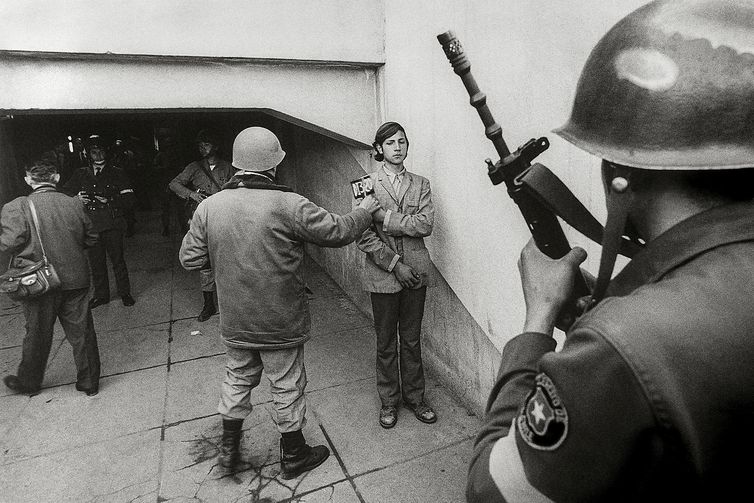

With the borders closed by the Chilean military junta, he could only enter Santiago on September 21, when the press was allowed to record the event, but under heavy military surveillance.

With his analog camera kept inside his jacket and always ready to click, Teixeira managed to escape Chilean censorship and make the most important records of that period for the Brazilian press.

And it is these photos, produced in black and white for JB, are on exhibit starting this Tuesday (21) at Moreira Salles Institute in São Paulo.

The exhibition Evandro Teixeira, Chile, 1973 is free and will be on show until July 30.

The curator is Sergio Burgi, the photography coordinator at IMS.

“The exhibition looks primarily at the material that Evandro produced in Santiago days after the 1973 military coup. And this presentation is built in dialogue with what he had produced before in Brazil, also in the period of the military dictatorship – iconic images like the one taken at the Copacabana Fortress on April 1, 1964, the first day of the coup”, said Burgi, in an interview to Agência Brasil.

By the way, this photo produced by Teixeira about the taking of the Copacabana Fort, in which the military is shown under strong shadow and torrential rain in Rio de Janeiro, with only a light shining in the background, is one of his favorite records.

After visiting the exhibition in his honor in São Paulo, Teixeira told how the image was made.

“At 5 am, Leno [Captain Leno, his neighbor in Rio de Janeiro] knocked on my door saying that the military coup was happening. ‘Are you coming with me or not?’ he said. At that moment, I put the camera inside my jacket, filled my pockets with film, and took only a 35mm lens. And off I went,” said the photojournalist.

And this is how he caught the first glimpse of the 1964 coup.

The exhibition presents 160 photos, besides books, videos, facsimiles, press badges, and even the camera that Teixeira had to take to Chile to transmit his analog photos to Brazil.

Of the 160 photos on display, 130 present images he made in that country.

The rest are photos in which he portrays the Brazilian dictatorship.

Among them is one of the most famous, in which he recorded hundreds of people crowded in Cinelândia, in downtown Rio, holding a banner that reads: Down with Dictatorship, People in Power, taken during the “Passeata dos 100 mil” [March of the 100 thousand].

The photo, which had been chosen to be on the cover of the Jornal do Brasil, was censored by the military and could not make the front page of the newspaper.

But it became one of the best-known images of the Brazilian military dictatorship.

“He made a series of images of the demonstrations of 1968, which began with the murder of student Edson Luis (Edson Luís de Lima Souto, killed by the Brazilian military), went through the repressed seventh-day mass in Candelária, which then culminated in the so-called ‘bloody Friday’ [an event in which the military repressed a student march, causing the death of at least 28 people].”

“And, finally, it also depicted the ‘Passeata dos 100 mil’,” explained Burgi.

EXHIBITION ROOMS

The exhibition presents three prominent sets of images Teixeira took on this trip to Chile.

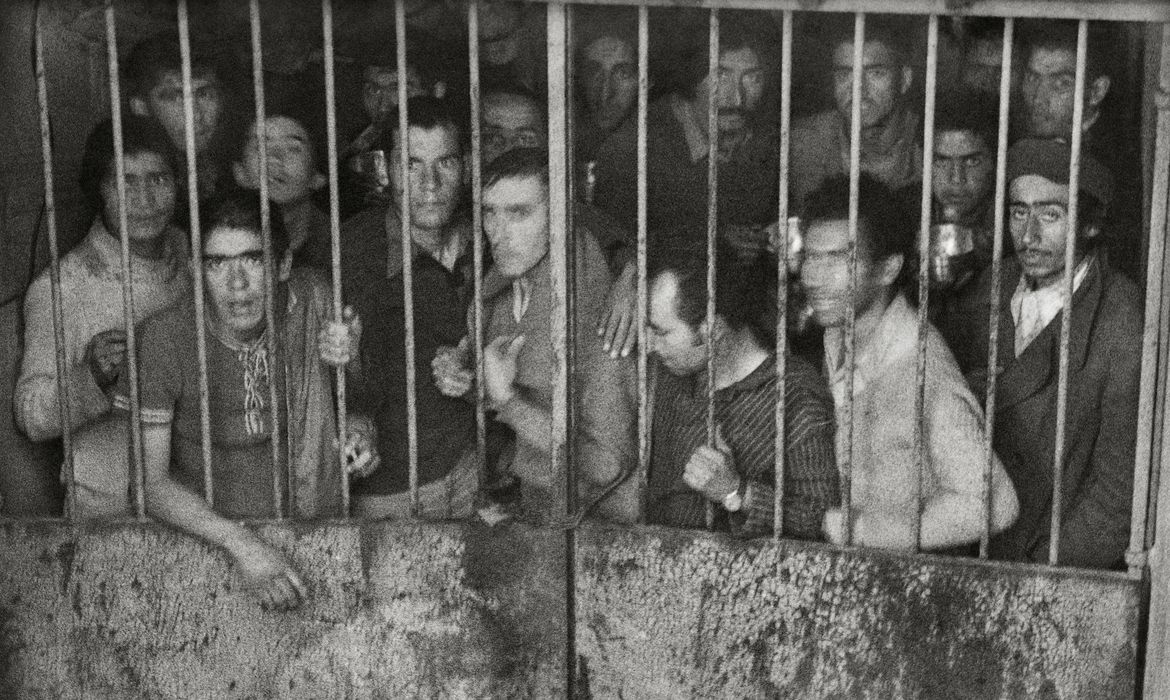

The first space presents photos he took of the Brazilian dictatorship and images in which he depicted what happened in Chile’s National Stadium, which “transformed into a detention, torture and murder camp”, according to the curator.

In this session of the exhibition hall, the curator put aside the images made in the stadium that was staged by the military, showing a few political prisoners in the stands and a colonel giving an interview.

He said that they all received good treatment in the prisons.

On the other side were the photos that Evandro took when he managed to free himself from the military and entered the stadium basement, showing the students being arrested.

“The [Chilean] military junta, by releasing the international press, tried to reconstruct an upside-down narrative of what was happening in the National Stadium.”

“He [Teixeira] and dozens of photojournalists were taken to the stadium, which was previously prepared with only 10% of the prisoners chosen to be there in the stands.”

“While the colonel gave an interview saying that the prisoners were entitled to sunbathing and medical attention, Evandro, who already knew the place from covering the World Cup, went down to the basement and showed images of students arriving prisoners,” said the curator.

Evandro Teixeira remembers this moment well. While visiting the exhibition on Monday (21), he told Agência Brasil what it was like to experience this part of history.

“It was a tense moment at the National Stadium, for example. As I knew the stadium, for having been to the 1962 World Cup, I knew where I was weighing. I knew there was a basement there.”

“And then, when I was accompanying the [official] visit to the stadium, when [that presentation] was over, I took off and quickly made half a dozen photograms of arrested students leaning against the wall. And they all died. Everyone who was in the photogram died,” he recounted.

The exhibition room’s second space presents photos he took in the streets of Santiago.

This is also where you can find the telephoto machine that worked as a fax machine and that he used to send pictures from Chile to Jornal do Brasil.

“Here there is a series of images of the bombed La Moneda Palace, the city occupied by the Army, and the peripheral cemetery with open graves,” described the curator.

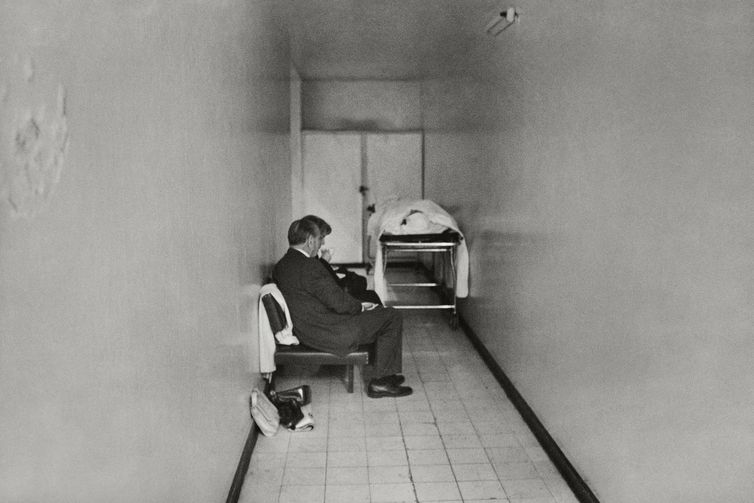

The third space presents Teixeira’s images about the death and burial of Chilean poet Pablo Neruda.

The photographer had met Neruda and his wife Matilde while still in Brazil when they were in Salvador to visit the writer Jorge Amado.

When he arrived in Chile to portray the dictatorship, Teixeira learned that Neruda was hospitalized in a clinic.

He went there. There he found Neruda dead and made the poet’s only and last records.

“He went with a hidden camera, managed to get through a side entrance, and reached an area where Neruda’s body had been brought for the preparation [of the burial].”

“There’s an important photo that he makes, the first of them, where Neruda’s widow is [next to the body].”

“He took the photo and introduced himself to her, remembering their visit to Jorge Amado. And then she asked him to stay there and accompany her.”

“The photojournalist took 36 hours of documentation between the clinic, their house, the wake, and the funeral.”

“This ended up becoming the first political manifestation against [Augusto] Pinochet’s regime,” said the curator.

The photos of Neruda’s death and burial are presented, accompanied by excerpts from his poetry.

“There is a picture of Doña Matilde in a cubicle next to the door through which I entered. When the door to the Santa Maria Clinic opened, I was walking around and looking for a place to enter.”

“I saw a little open door and went in. When I entered that cubicle, I saw Neruda’s body on a stretcher and Ms. Matilde beside it. And then I clicked.”

“First, I photographed, and then I told her I was the photographer [who made images] of Jorge Amado. Do you remember?”

“Then she looked at me and said: ‘my son, your presence here is very important’,” recalled Teixeira.

His widow then authorized him to photograph the poet’s wake and burial, which was attended by a large crowd.

“It was very emotional. I cried there. I approached the tomb to photograph it from above and saw people chanting: ‘Neruda is alive’.”

“And then I cried. With the tears that were shed, I held myself back. It was a beautiful moment,” he said.

THE DICTATORSHIPS

In the interview with Agência Brasil, the photojournalist who lived through the violent periods of military dictatorship in Brazil and Chile said there are no differences between them.

And he stressed that knowing about this period in the history of the two countries is essential, so society will never allow the dictatorships to return.

“That thing that happened in Brasilia [the invasion of the three branches of government in early January of this year] was a shame. That gave me a business. That was a sad thing,” he lamented.

Teixeira will participate in a chat with the public this Tuesday, starting at 6 pm.

The conversation, which will also include the presence of the exhibition’s curator, will discuss dictatorships and the importance of democratic regimes.

“It’s a significant exhibition because it fundamentally talks about the question of the rule of law and the meaning of violence every time you break that,” Burgi said.

“This kind of exhibition is important to teach new generations what dictatorship is. Unlike Brazil, Argentina and Chile had a trial process [of those responsible for the torture and deaths of the period] that allowed the new generations to know the history.”

“As in Brazil there were no such trials, this type of initiative, the exhibition, is fundamental,” said Carina, the photographer’s daughter.

The chat should also include the importance of the photojournalist’s role in historical records.

“My adventure identifies with the adventure experienced by the world. I have no merits for this; I am a man handling a camera. When well operated, it is a lighted match in the darkness.”

“It illuminates facts that are not always very understandable. It offers glimpses and reveals the pains of the impasse of the world.”

“And awakens in men the desire to destroy this impasse,” said the photographer in a text about the exhibition.

The exhibition at Moreira Salles Institute has free admission. More information can be obtained at the exhibition’s site.

“I hope that many people come to see it because, modesty aside, I still didn’t have the dimension of the quality and quantity of what I had done,” the photographer told the reportage.

With information from Agência Brasil