By Filipe Serrano

The new government of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (PT), who took office this Sunday (1), has a series of challenges in the economy that should define the success or not of his third term.

The main one will be to adopt a responsible public spending policy and develop a new fiscal anchor to replace the current spending ceiling rule.

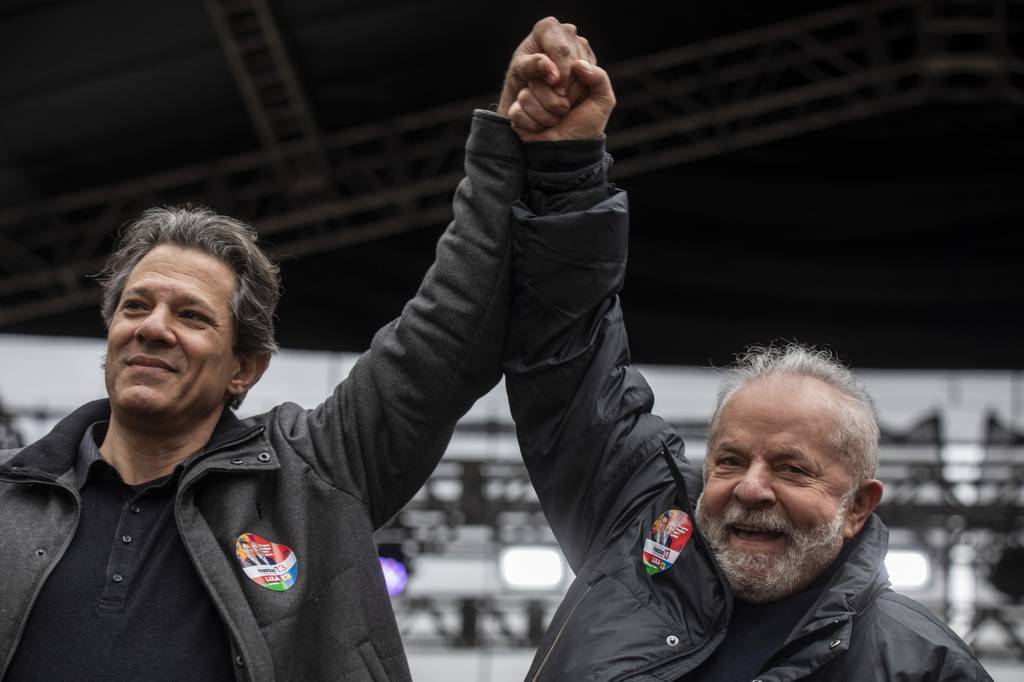

With Fernando Haddad in the Ministry of Finance, Lula da Silva will face a less favorable economic scenario than the one faced by the now former president Jair Bolsonaro in 2022.

In addition to the pressure to increase public spending, the trend this year is a loss of growth of tax revenues and the slowdown of the economy in Brazil and around the world.

The high interest rate, currently at 13.75% per year, increases the cost of credit and puts pressure on economic activity. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which should end the year with an annual expansion of around 3%, tends to slow down to 0.79%, according to financial market estimates published in the Central Bank’s Focus Bulletin.

In recent weeks, Bloomberg Línea has spoken with economists and studied reports from financial institutions to gauge the outlook for the economy under Lula da Silva’s government.

See below what are the main challenges of the new Government in economic matters:

1. BALANCE OF PUBLIC ACCOUNTS

The main uncertainty regarding the Lula da Silva government is the conduct of fiscal policy. The signs of an increase in public spending without compensation or clearer control in the medium and long term are the issues that most worry financial market analysts.

Uncertainty persists even after Congress approved the transition PEC at the end of December, which increased the spending limit provided for in the spending ceiling rule. The PEC releases an amount greater than R$145 billion for the ceiling and withdraws from the fiscal rule R$23 billion related to the increase in revenue for public investments, adding a total increase of R$178 billion by 2023.

The objective of the measure is to allow the maintenance of the payment of the Bolsa Família social program at R$600 and to recompose the expenses for the Popular Pharmacy, School Lunch and Gas Aid programs, among other expenses.

The expansion of the spending ceiling will only be valid for one year, unlike the four years previously advocated by Lula da Silva’s team. The value was also below the more than R$200 billion reais of the original proposal.

Even dehydrated, the PEC should lead to a significant increase in federal government spending, which should rise from 18.3% of GDP in 2022 to 19.4% in 2023, according to calculations by BTG economists led by the economist Chief Mansueto Almeida, former Secretary of the National Treasury.

This is a reversal of the downward trend in spending relative to GDP in recent years. Economists estimate that the government will have to increase tax revenue to offset the increase in spending. One possibility would be to review federal subsidies and re-collect federal Cide, PIS and Cofins taxes on fuel.

Taxes were reduced to zero in mid-2022 until December 31. At the end of the year, Fernando Haddad asked former Economy Minister Paulo Guedes not to extend the exoneration and said that the government would re-evaluate the case after he took office.

The estimate is that the return of tax collection can produce about R$53 billion in revenue in 12 months. The amount is insufficient to cover the increase in PEC spending and Brazil may end the year with a primary deficit of -1.2% of GDP, after reaching a surplus in 2022.

“The deterioration of the primary result, as well as the maintenance of Selic at a high level for longer, should translate into a growth of almost 5 points of GDP for gross debt, going from 73.8% in 2022 to 78.2% in 2023″, says BTG, in a report.

Haddad has indicated that the Government will work on drafting a new fiscal anchor to replace the current format of the spending ceiling rule, which is considered obsolete as it has been punctured several times in the last two years.

Although this new standard is not defined, the greatest risk is that public spending enters into an unsustainable growth path, reducing market confidence in the control of public accounts.

“The big test will be the design of the the fiscal framework,” said Alessandra Ribeiro, economist and managing partner of the consultancy Tendências. “From there we will understand in which area of fiscal policy we are operating. If we create a new framework that allows for a very substantial real increase in spending, we can enter a pessimistic trajectory for the Brazilian economy, with the return of macro instability.”

In the most pessimistic scenario, the trend would be an upward trend in the country’s yield curve and the risk of a depreciation of the real against the dollar, which would possibly force the Central Bank to further raise the basic interest rate to combat the pressure of the exchange rate and fiscal expansion on inflation.

Since Lula da Silva’s election at the end of October, the average market estimate for the Selic rate at the end of 2023 has gone from 11% to 12.25% per year, according to the Focus bulletin.

2. SLOWDOWN OF THE BRAZILIAN AND WORLD ECONOMY

After the 2020 pandemic shock, the Brazilian economy had two consecutive years of strong recovery in 2021 and 2022.

The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) advanced by 4.62% in 2021 and will close 2022 with an increase of around 3%. For 2023, however, the outlook is for a slowdown, according to financial market economists. Itaú, for example, forecasts an expansion of 0.9% this year. Bradesco estimates growth of 1%, while Santander sees an increase of 0.8% and BTG of 0.7%.

The slowdown has to do with the loss of strength in the segments most closely linked to on-site activities that had been affected by the pandemic, such as the services sector.

In addition, keeping the Selic rate at a high level tends to keep the cost of credit high, reducing activity in the segments that are most dependent on loans, such as civil construction and automobiles.

Abroad, expectations also point to a slowdown in the world economy, with a risk of recession in the countries of the euro zone and the United States, also due to high interest rates.

In this more difficult environment for the world economy, Brazilian export sectors, such as iron ore and agribusiness, end up suffering from the drop in demand and international prices for raw materials.

It is a more unfavorable economic scenario for Brazil and for the government of President Lula da Silva. “In his first and second terms, Lula da Silva had a very calm and very favorable global situation during a good part of his government,” said Roberto Padovani, chief economist at BV (formerly Banco Votorantim). “Now it is the opposite situation. We had the pandemic in 2020, then a rapid recovery in the world, with growth around 6%. What we are seeing now is a process of adjustment.”

Padovani points out that the expansion of public spending in a scenario of economic slowdown and possible drop in revenue tends to put more pressure on the government’s fiscal result.

In his assessment, the combination of fiscal uncertainty and a weakening world economy tends to keep pressure on the exchange rate.

Alessandra Ribeiro, from Tendências, has a similar opinion. “Depending on the decisions we make in the economic sphere, we may be penalized more or less,” she says. “We have a very different foreign environment than in recent years, when interest rates were very low and liquidity was very high abroad. The market was less selective because the cost of money was lower than it is today. All this context weighs positively for the Brazilian economy”.

3. INFLATION

After reaching a maximum of 12.13% in April, the 12-month accumulated IPCA (Consumer Price Index) fell to 5.90% in November.

The fall in the main inflation index was influenced by the monetary tightening of the Central Bank, which raised the Selic rate to 13.75% per year, and also by federal and state tax cuts on products such as fuel and electricity.

It has also helped that the exchange rate is more controlled and that the price of raw materials has stabilized or even fallen since mid-2022.

For 2023, the outlook is for lower inflationary pressures, but the financial market expects the IPCA to close the year at 5.23%, above the Central Bank’s target of 4.75%.

If the Lula da Silva government chooses to end the subsidies and go back to collecting federal taxes on fuel,, inflation may rise. The LCA consultancy, for example, forecasts an increase of 0.9 percentage points in the IPCA in 2023 due to the end of the exemption on gasoline, diesel, ethanol and natural gas.

According to LCA, the uncertainty about the end of the tax exemptions has caused an increase in the difference in forecasts for the IPCA in the financial markets. The increase in public spending and the lack of definition regarding a new fiscal framework have also led to estimates of a slower deceleration of inflation.

“The possibility of a faster tax reduction is one of the two main reasons why our inflation forecasts for 2023 now have an upward bias,” the consultancy says in a recent report. “The other reason is the expectation of a greater fiscal boost in the short term derived from the approval of the Transition PEC.”

In this environment, economists consider that the Central Bank tends to keep interest rates high for longer. Before Lula’s election, the estimate was that Copom could reduce the Selic rate in the first semester. Today, the assessment is that this should only happen in the second semester.

4. TAX REFORM

The tax reform has been pointed out for years by economists and experts as one of the most necessary legislative changes to reduce tax complexity in the country, reduce bureaucracy and increase productivity and competitiveness in Brazil.

With the appointment of economist Bernard Appy to the Treasury Ministry’s Special Secretariat for Fiscal Reform, the government is expected to prioritize reform. Appy is the mentor of the current tax reform proposal in Congress, PEC 45/2019.

The bill provides for the replacement of federal and state taxes by a single tax called IBS (Goods and Services Tax), similar to VAT (Value Added Tax), used in several countries. Fernando Haddad, appointed Minister of Finance, He has stated that tax reform will be one of the main priorities at the start of Lula’s government. In addition to PEC 45, another similar proposal is also pending in Congress, PEC 110.

“Appy’s placement to champion the draft of PEC 45, or perhaps PEC 110, is very positive. These are reforms that, unfortunately, the Bolsonaro government, with the economic team, did not buy and did not want to carry out. We wasted a lot of time with this. If we really manage to approve this broad tax reform project, we can have very positive impacts for productivity and potential GDP”, affirms Alessandra Ribeiro, economist and partner-director of the Tendências consultancy.

5. MAINTAIN REFORMS AND LEGAL FRAMEWORKS

Since the government of Michel Temer, who assumed the presidency after the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff in 2016, Brazil has managed to pass a series of reforms and important legal milestones to increase the dynamism of the Brazilian economy.

Among them, the labor reform stands out, which reduced the legal risk for companies of labor lawsuits, and the pension reform, which made it possible to reduce the trajectory of pension expenses, which represent almost half of the Government’s primary spending.

The Central Bank Autonomy Law was also approved, which establishes a fixed term of four years for the president of the Central Bank, interspersed with the election for president of the Republic; the Law of Economic Freedom, to reduce the bureaucracy of the companies; and the New Exchange Framework, which consolidates the rules for foreign currency operations.

In addition, the Sanitation Legal Framework encouraged privatization and increased investment in the public water and sewerage service, one of Brazil’s bottlenecks. Almost half of the Brazilian population (or 100 million people) does not have access to a sewerage network, according to the Ministry of Regional Development (MDR).

Other recently approved reforms were also important, such as the Cabotage Framework, to facilitate maritime transport along the Brazilian coast, and the Railway Framework, which allows the construction of railways proposed and built by private initiative.

In the assessment of Alessandra Ribeiro, economist and managing partner of Tendências, one of the challenges for the Lula da Silva government will be precisely to maintain the economic agency that stimulates the private sector, without making changes to the reforms that have worked in Brazil.

Lula da Silva has said since the campaign that he intends to review some points of the labor reform, which worries the private sector. Before the law, one of the big legal costs was labor lawsuits, which plummeted after it was passed.

“It is a challenge to maintain the reforms so that the country can reap all the positive effects”, affirms Alessandra Ribeiro. “We see here and there complicated statements, which point to setbacks, which for the country would be a great loss, since we have not even begun to reap the benefits of all this agenda implemented since mid-2016.”

The economist also points out the importance of maintaining the agenda of innovations implemented by the Central Bank, which have not only allowed greater agility and ease for means of payment, such as Pix, but also seek to increase the competitiveness of the financial and banking system. “The preservation of this agenda is essential,” she says.

With information from Bloomberg