In the transition from the first to the second round of the presidential election, Jair Bolsonaro (Liberal Party – PL, right) got more “new votes” than former President Lula da Silva (Workers’ Party – PT, left), even though the PT’s president got the best results in the total count.

Compared with their votes in the first round, da Silva gained almost 3.1 million new votes, and Bolsonaro gained 7.1 million. In the absolute number of votes, Bolsonaro also grew more than Lula da Silva in every state.

This growth was not enough to prevent the victory of the PT candidate, who added 60.35 million voters (50.9% of the valid votes) and became the president-elect of Brazil.

Still, Bolsonaro’s advance explains the tight national result, with just over 2 million votes ahead of Lula da Silva (down from the over 6 million votes advantage da Silva had at the end of the first round).

Bolsonaro’s biggest advance since the first round occurred in all the states of the Northeastern region, Lula da Silva’s electoral stronghold.

This growth in the Northeast did not change the result in the region, and Lula da Silva continued to win in almost all Northeastern states with more than 60% or even 70% of the vote (except Alagoas, where da Silva won with 58.7%).

Still, one of the objectives of Lula’s campaign was to further extend the advantage against Bolsonaro in the Northeast, which did not occur to the extent predicted.

Moreover, in states in the North, such as Acre, Amazonas, and Amapá, Lula da Silva even shrank, losing votes.

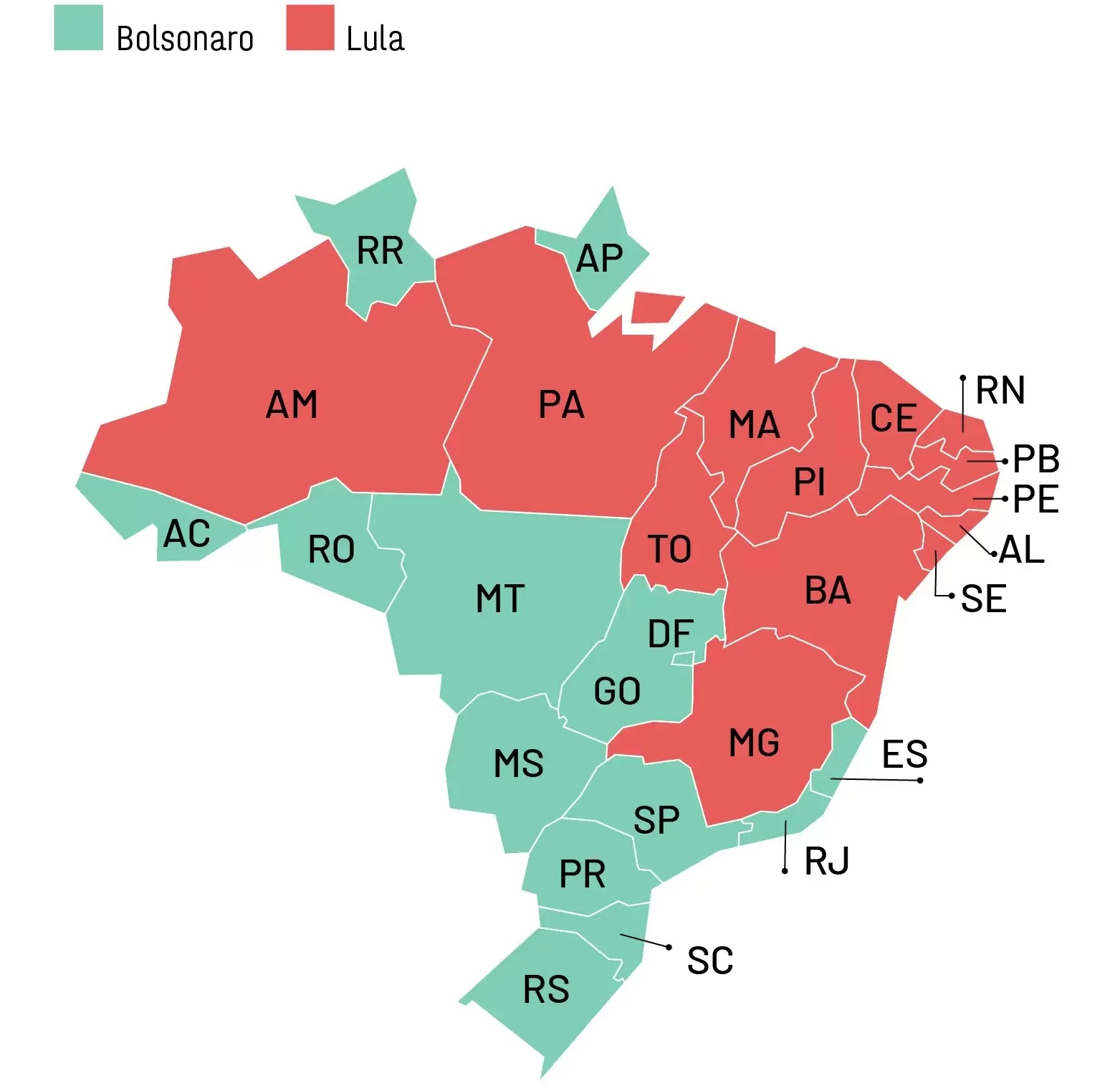

Amapá was also the only state that changed sides, with da Silva losing in the second round after winning in the first.

The “damage reduction” in the Southeast

So, in the aggregate, da Silva only won the election because he also took valuable votes in populous states where Bolsonaro won.

The biggest highlight was the Southeast region, which has Brazil’s three largest electoral colleges: São Paulo, Minas Gerais, and Rio de Janeiro.

In 2018, Bolsonaro won in the Southeast by a wide margin. In 2022, he remained ahead and won in three of the region’s four states (except for Minas Gerais, where Lula da Silva won).

The result in detail, however, shows that the current president’s performance has worsened in the southeastern states compared to 2018, when Bolsonaro was elected president against then-PT candidate Fernando Haddad.

One of the mantras among political scientists explaining this difference is the analysis that “Lula da Silva’s votes are not PT’s votes,” given the president-elect’s personal popularity, which would have been clear in the 2018 election, in which da Silva did not contest.

Be that as it may, this better PT performance (and worse Bolsonaro performance) compared to the last election is not unique to the Southeast and can be seen in all states.

But the movement generates a more significant impact on the national result exactly when coming from the largest electoral centers.

Another highlight in the “damage reduction” of the PT campaign was Rio Grande do Sul, the fifth largest electoral college in the country and where Bolsonaro’s advantage also fell, pulled by good votes for Lula da Silva in the metropolitan region.

SÃO PAULO (SP) (2018 x 2022):

In 2018, Bolsonaro had 8.1 million more votes than Haddad in SP;

In 2022, Bolsonaro had 2.7 million more votes than da Silva;

RIO DE JANEIRO (2018 x 2022)

In Rio, in 2018, Bolsonaro had almost 3 million more votes than Haddad;

In 2022, Bolsonaro had 1.2 million more votes than da Silva;

MINAS GERAIS (2018 x 2022)

In Minas, in 2018, Bolsonaro had almost 1.7 million more votes than Haddad;

In 2022, Bolsonaro lost in Minas by a tight margin, with almost 50,000 fewer votes than da Silva.

RIO GRANDE DO SUL (RS) (2018 x 2022)

In RS, in 2018, Bolsonaro had over 1.6 million more votes than Haddad;

In 2022, Bolsonaro had just under 900,000 more votes than da Silva.

Lula da Silva’s better result compared to Haddad in 2018 was pulled by some decisive big cities, such as São Paulo and Porto Alegre, as well as their respective metropolitan regions, where Haddad had lost, but Lula da Silva won.

In the city of São Paulo alone, which has more than 9 million voters (almost a third of all voters in the state), Lula da Silva had 53.5% of the vote, against 46.5% for Bolsonaro.

The victory in the São Paulo capital gave Lula da Silva a balance of almost 500,000 votes, valuable in such a tight national election.

Even with Bolsonaro’s victory in the state, pulled by votes from the interior, the city of São Paulo alone gave da Silva a bigger balance, in absolute numbers, than many states gave Bolsonaro, such as Rondônia, Roraima, or Mato Grosso do Sul.

São Paulo also came close to generating a greater balance of votes for da Silva than the entire state of Mato Grosso did for Bolsonaro (there, the president had 563,000 more votes than Lula da Silva).

THE LIMITS OF THE BROAD FRONT

At the same time, the difference between the first and second rounds means that most of the other candidates’ voters chose Bolsonaro over Lula da Silva, even with the support of names like Simone Tebet (MDB) and Ciro Gomes (PDT) in a broad front in the PT campaign.

The list of candidates in the first round also included names that did not support Lula da Silva, such as Soraya Thronicke (União Brasil) and Luiz Felipe D’Ávila (Novo).

But the two together got a little less than 1.2 million votes, while Ciro and Tebet got more than 8.5 million.

In other words, for Bolsonaro to have a variation of more than 7 million, an important slice of several electorates, especially Ciro and Tebet, had to migrate to the current president.

It is something that had already occurred in the final stretch of the first round, in a movement based on anti-PT sentiment, as EXAME showed.

But the results of the runoff show that there was still room for a new wave of support for Bolsonaro – although not enough to guarantee the reelection of the current president.

With information from Exame