By Marcelo Contreras

RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Commander Juan López Lermanda opens the envelope on the high seas and reads the brief order from the government of President Domingo Santa María. In a few words, he trusts his criteria to operate in Panama, a territory belonging to Colombia with separatist ambitions. Officially he must protect the interests of Chilean residents, but the real mission is to prevent the United States from taking advantage of the revolt to establish its hegemony in the area. For the task, López Lermanda has the best technology of the moment at the command of the Esmeralda cruiser, the latest acquisition of the navy. It’s the end of April 1885 and the ship, described by the New York defense publication Army and Navy Journal as “the finest, fastest and most perfectly equipped warship of her size afloat”, records just six months of service.

The Esmeralda cuts the waters with an unusual average speed of 12.6 knots, equivalent to 23.3 kilometers per hour, arriving in just four and a half days at the port of Colón, Panama, on April 28. The crews of French and American warships stationed in the bay carefully observe the Chilean cruiser that breaks the mold of naval architecture. In addition to its extraordinary speed with a maximum speed of 18.3 knots, other innovative characteristics are added: it is the first warship in history that does not use sails, its 10-inch central artillery is typical of a battleship, and it offers little target due to its low height design.

Read also: Check out our coverage on Chile

The arrival of the Esmeralda causes surprise and some irritation in the powers present. Why has Chile sent such a weapon to Panama? U.S. officials rush to schedule visits to the cruise ship. “The applause was unanimous,” said Commander López Lermanda in a detailed mission report written on his return to Callao. “The press dealt with our ship many times, drawing attention to this war machine, as the most powerful and fastest that was afloat in its class.”

The story of López Lermanda, decorated by Tsar Alexander III for towing a Russian ship from the southern tip to Valparaíso in 1871, highlights the vivid North American curiosity. “Not satisfied with the repeated views that were made to get to know the ship, they took sketches and notes of of her most insignificant details.”

Sailors from the North Country warn of a hypothetical situation in the Army and Navy Journal. The Esmeralda is capable of bombing the city of San Francisco without taking damage. The wooden corvettes and frigates that make up the North American Pacific fleet had no chance against the Chilean ship that, during its construction period between 1881 and 1883, had been visited by the Prince of Wales and future King of England Edward VII, due to its advanced qualities that to this day point to it as the first protected cruiser in history.

Voices appear in the U.S. Congress demanding modernization and reinforcement of the fleet on the west coast because Chile, winner of the War of the Pacific and new owner of extensive territories seized from Peru and Bolivia, with armed forces experienced in bloody sea and land combats for four years, represents a threat.

The modest South American nation, one of the poorest in the days of the Hispanic colonies, had rejected U.S. intervention in 1882 to settle the armed conflict between the three Andean countries. Chile had ships and armies to rule out biased mediation in favor of the allies, as U.S. policy had shown during the conflict.

At the beginning of the War of the Pacific, the national squad faced serious problems to neutralize the Huáscar monitor and the Unión corvette, thanks to its greater speed. Although they were older ships, the poor maintenance of the Chilean ships allowed Admiral Miguel Grau to keep the naval force of Rear Admiral Juan Williams Rebolledo in check, unusually convinced of the superiority of the Peruvian ship, despite the armored Cochrane and Blanco Encalada had greater armor and fire power, compared to the ship where Captain Arturo Prat had fallen. The Huáscar spread fear even in Valparaíso, where it was believed that she could bomb at will, outwitting the slow Chilean naval division.

The ships were refurbished, there were changes of command and the Huáscar was captured and integrated into the fleet on October 8, 1879 in the battle of Angamos. The army learned lessons. It needed fast ships.

“Inscribed in that idea, Chile ordered the Arturo Prat cruiser, with a speed of 16.5 knots in the middle of the war,” explains Carlos Tromben, doctor in Maritime History from the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom. However, el Prat never reached Chile. “She couldn’t be delivered during the war, she didn’t run and she was sold to Japan. Chile persisted in the idea of having fast ships and the result was the Esmeralda, the fastest in its time.”

“It looked towards the 20th century in its design and conception”, points out the journalist and historical researcher Piero Castagneto. “Although she did not have turrets, but barbettes, her main artillery was swivel guns at a wide angle. Her secondary artillery had a layout that remained that way for a long time, well into the new century. If you compare the Esmeralda of 1884 with a cruiser of 1900, there are no substantial differences.”

As for the mission of the Esmeralda in Panama, both the Navy and the Chilean Foreign Ministry took care not to leave records. “The navy’s report, like the RR.EE. (Ministry of Foreign Affairs), say nothing”, reveals Tromben. “The only thing there is is López Lermanda’s book, with memories of the War of the Pacific, and the report that I located in the national archive, which gave rise to the articles that I have written.”

For Dr. Tromben, naval power was an active agent of national diplomatic relations during this period, supported by a generous fleet of battleships and cruisers that the country continued to incorporate until the beginning of the 20th century. Chile was engaged in a costly arms race with Argentina that left both countries considerably indebted. “These ships began to be used in support of Chilean foreign policy. There were visits to Ecuador, Central America, Europe, to show the flag and the capacity in this matter”.

If under the government of Domingo Santa María (1881-1886) the Chilean squadron had three armored vehicles, a cruiser, three corvettes and a gunboat, in a position to challenge the American ships of the Pacific with advantages, his successor José Manuel Balmaceda commissioned more ships to ensure naval supremacy.

“He orders the construction of the first Talcahuano dam and renews the fleet with a battleship, two modern cruisers, plus two torpedo boats and two cutters”, Piero Castagneto lists.

“Today it sounds crazy”, continues the journalist, “but the country needed a viable hypothesis of armed conflict with the U.S. because they were showing signs of wanting to influence the continent more and more. In fact we know that Chile was relieved of this hypothesis when the U.S. focused on the Caribbean, intervenes in Cuba’s war of independence and defeats Spain, annexing Puerto Rico and the Philippines.”

Carlos Tromben adds other variables to the complex Chilean international situation at the end of the 19th century with different potential conflicts. “There were border problems with Argentina, and in turn, Argentina had a naval race with Brazil. There were also issues with Peru and Bolivia that took decades to reach agreements. All that made it advisable to have a respectable naval force.”

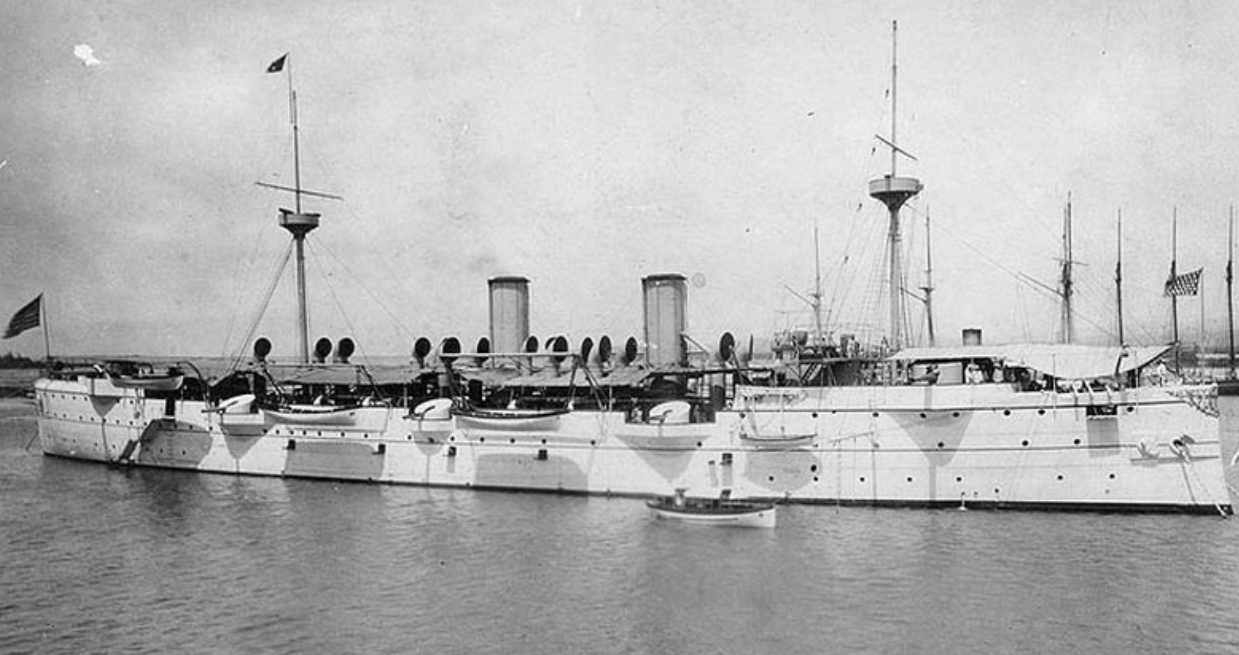

However, the facts confirmed that the tricolor supremacy at sea came to an end with the murder of two sailors and another 17 wounded from the Baltimore cruiser in Valparaíso in October 1891, after an American crew member spit on a portrait of Arturo Prat in a Buenos Aires bar, causing a brawl worthy of the old west. At first, the Chilean government refused to apologize and pay compensation to the affected families, until the U.S. hinted at the possibility of war.

Launched in 1888 with 4,413 tons and a speed of 19 knots, the Baltimore somehow represented the American reaction to the Chilean squadron.

Although Chile lost its naval power towards the end of the 1980s in the face of the United States and then Argentina, which had a much more homogeneous acquisition program – “Chilean cruisers were very different in models, speeds and armaments making logistics difficult”, says Tromben-, the navy stars in the last acts as a maritime power.

In 1888 Chile annexed Easter Island, as a result of the hard work of Commander Policarpo Toro, who raised with the government the strategic importance it represented for the country, personally managing the purchase of the island territory in Tahiti.

Meanwhile, the Esmeralda cruiser continued an intense log that would cross it again with U.S. forces during the civil war of 1891, when the navy allied with Congress to overthrow the Balmaceda government. The speedy ship escorted the Itata transport, destined to ship weapons for the rebel parliament in San Diego. The Esmeralda waited in Mexican waters for the merchant ship, due to the U.S. government’s support for Balmaceda. The Itata picked up the cargo and in a daring maneuver managed to escape from the authorities who had held the ship. Pursued by the cruiser Charleston to Acapulco, a May 16 New York Times report speculated on the possibility of a battle between the two ships, which ultimately came to nothing.

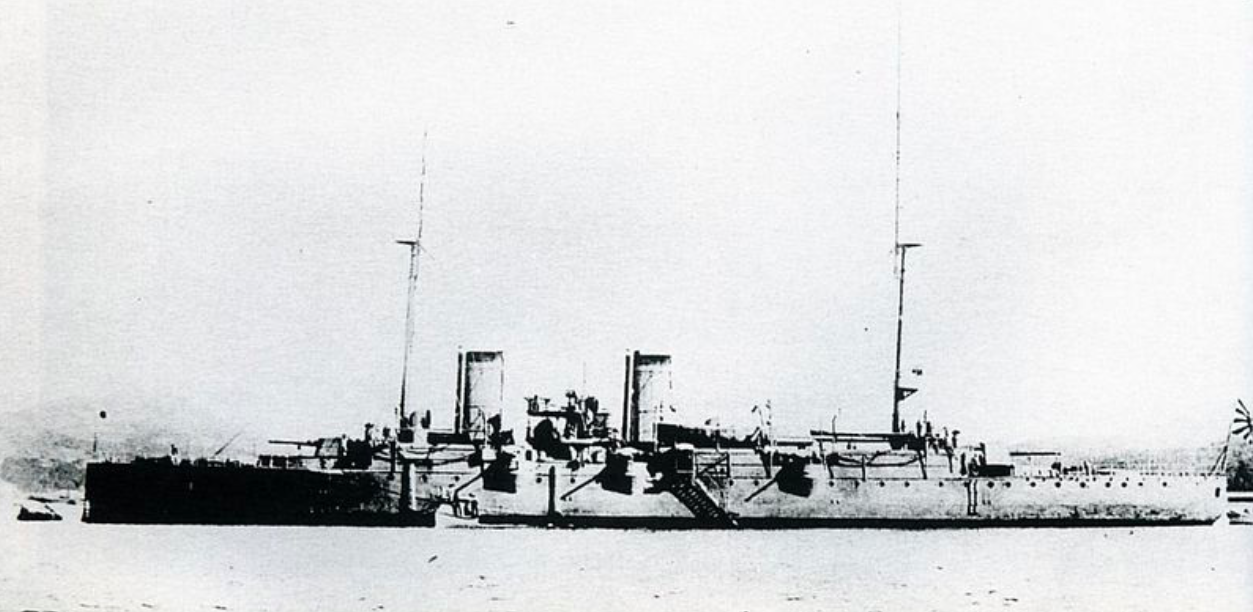

Three years later, with an exact decade of busy services to the Chilean navy, the Esmeralda was sold to Japan, completing the second arms deal with the empire of the rising sun in 15 years, an impossible exercise today.

Why did Chile get rid of the ship?

“Two technical reasons”, responds Carlos Tromben. “She had a high carbon consumption and a high tendency to corrosion. That’s why she was sold to Japan. She was renamed Itzumi and acted late in the war between China and Japan. She was negotiated through Ecuador, because Chile had an agreement with China and could not sell it directly. The ship then saw action in the Russo-Japanese War at the Battle of Tsushima, sighting the Russian Baltic fleet. In Japan she was discharged in 1912.″