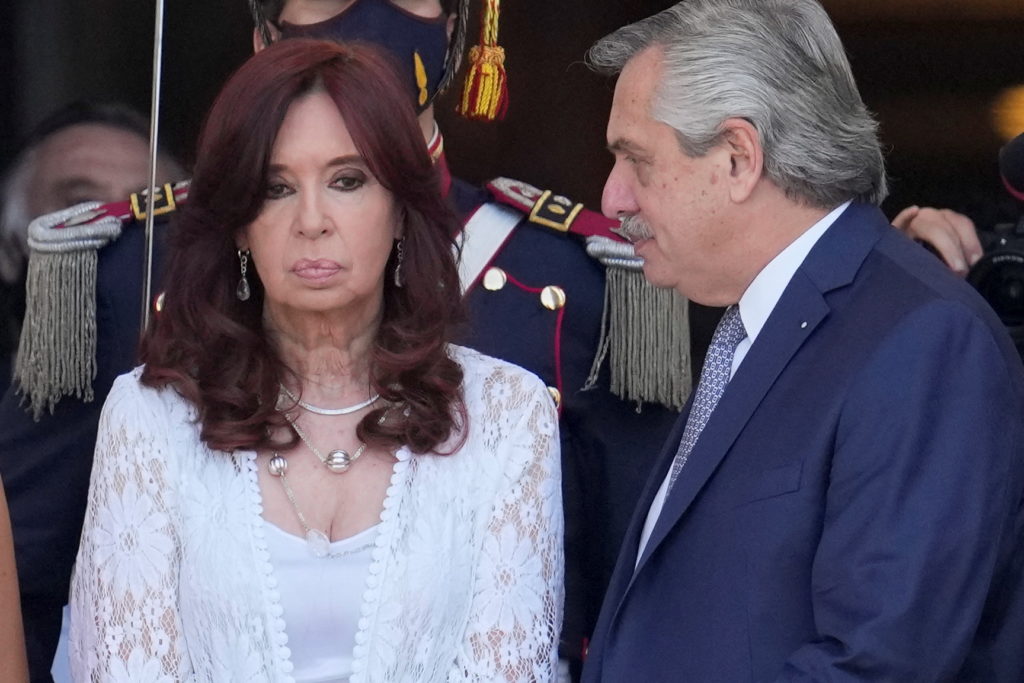

RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Argentina is suffering the consequences of a divorce. A non-consensual divorce, one of those that go to court, and the passion of yesteryear is now fuel for the most bitter disputes. The South American country suffers the political miseries of leadership that settles its quarrels loudly. President Alberto Fernández and his vice-president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, no longer speak to each other. The background is the power rivalry and the differences in the course they both intend for Argentina. And the sin of birth: Alberto Fernández was anointed by Cristina Kirchner as a presidential candidate and owes his seat in the Casa Rosada to her. The experiment worked to avoid a second term for Mauricio Macri in October 2019, but the political anomaly of a vice-president with more power than a president has been a failure once in government.

Last Thursday, Argentina commemorated the 46th anniversary of the military coup against Isabel Perón. President Fernandez held a small protocol act, while Cristina Kirchner and her political grouping, La Campora, mobilized 70,000 to the Plaza de Mayo, the quintessence of political power in Argentina. Leading the mobilization was Máximo Kirchner, the vice president’s son. La Campora showed street muscle and sent a clear message to the Casa Rosada: we are the people, the real electoral base of the government, the creditors of the presidential power. Meanwhile, Fernández calls for unity, convinced that the only possibility of winning in the general elections of 2023 is in a Peronism aligned behind a single candidate.

The blood between Alberto Fernandez and Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner came at the end of last year when the ruling Frente de Todos suffered a hard defeat in the mandatory primary elections. The Vice-President blamed her political dolphin for the loss. The ministers who answered to her resigned and forced Fernandez into a Cabinet reshuffle that was not in her plans. Two months later, the elections confirmed the defeat of the government’s candidates for Congress. Cristina Kirchner kept quiet, but the love affair with Fernandez, her former Chief of Staff, was over. The agreement that Argentina closed this week with the IMF for a debt of 45 billion dollars was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Kirchnerism voted against the text in Congress, arguing that an adjustment of the economy, as agreed by Fernandez, sentences to death any possibility of victory in the 2023 general elections.

“There are two groups that believe they have the right to make the decisions, two leaders who claim to have the power to decide ultimately,” says Sergio Morresi, a political scientist at the Universidad del Litoral. “And although the Argentine Constitution says that executive power rests exclusively with the president, the truth is that this vice president has a power of her own beyond her institutional place. And it is from that power of her own from where she demands that the president be considered to be there to fulfill a popular mandate of which she (and those who support her) feel they are the best interpreters,” he says. Andres Larroque, a strong man of Kirchnerism, said it clearly during the March 24 march. Fernandez, he said, “was the campaign manager of a space that got four points in the election of the province of Buenos Aires. Cristina’s initiative called the front”.

The president’s entourage does not agree with this reading of “borrowed power”. If Cristina Kirchner anointed him as a candidate, it was because she knew that she could not win on her own. Alberto Fernández is, under this reading, a necessary condition for the triumph of the Frente de Todos against Macri in 2019. Therefore, they argue, he has the right to exercise power as he pleases. These are different readings of reality. The economic crisis is pressing. Inflation is skyrocketing (already over 50% per year), and the president considers the IMF agreement the first step towards a way out. On the other hand, Kirchnerism maintains that nothing good can be expected from the IMF and that it is better to stay as far away from Fernández as possible as long as the Casa Rosada insists on moving towards the abyss without remedy. If the government they are part of fails, it is better to stay away from the shock wave.

Is Argentina headed towards a definitive breakup of the government coalition? “I don’t think so,” says Eduardo Fidanza, director of the consulting firm Poliarquía. “It does not suit any of the parties because it would fragment the Peronist vote and would ensure, from now on, an electoral defeat in 2023″, he says. Pablo Touzón, political scientist and director of Consultora Escenarios, does see the possibility of a terminal crisis. “There is a decision taken by Cristinismo: it considers that since the PASO [primaries] and the defeat in the legislative elections, the figure of Alberto Fernández has no leadership”, he explains. Sergio Morresi agrees that the crisis is “very serious”, but he considers that “beyond the will of a part of the leadership to finish breaking lances, there are other sectors, even in the bases, that are pushing to maintain the unity of the Frente de Todos”.

Among those sectors is Alberto Fernandez himself. During the last week, the president’s strategy has spread the idea that a fracture opens the doors to a return of the right-wing to power, represented by Mauricio Macri. Macri is, for Peronism, the consummation of all evils. Fernandez does not talk to his vice but makes calls from the media. “Whoever believes this will have any effect does not have the slightest idea of how the vice-president thinks,” said Cristina Kirchner’s entourage. The massive demonstration of March 24 was evidence of that: the real power is in the street and can be exhibited. And the rejection of the IMF was the banner.

In Argentina, however, nobody is very clear about where the way out of the quagmire is. “Cristinismo has a statement, but it does not have a real project for the country”, clarifies Pablo Touzón. “That is why he prefers to leave because he lacks an alternative solution to what the IMF is proposing. He wants to preserve a kind of core of values and meanings,” he says.

That core is the last hope of Cristina Kirchner and her movement, which sees as irremediable a failure of the government she conceived. Alberto Fernandez, meanwhile, is under pressure from his entourage to create “el albertismo”, a movement that breaks ties with Kirchnerism, supported by the power of the Peronist governors and the unions that support it.

“I do not grant many possibilities to Alberto Fernández, although he and his closest group believe he can aspire to reelection”, says Eduardo Fidanza. “In the current economic and social situation, his chances are very reduced,” he says. Sergio Morresi agrees. “In the first place, President Fernandez does not seem determined to launch a movement of his own and dispense with his partners, even if some of them want to dispense with him and move to undermine his ability to act. Secondly, it seems to me that we are going through a very delicate social and economic moment, and the conditions for launching a political movement of our own are not exactly optimal,” he says. Alberto Fernandez’s government has two years left in office and will have to navigate in the desert.