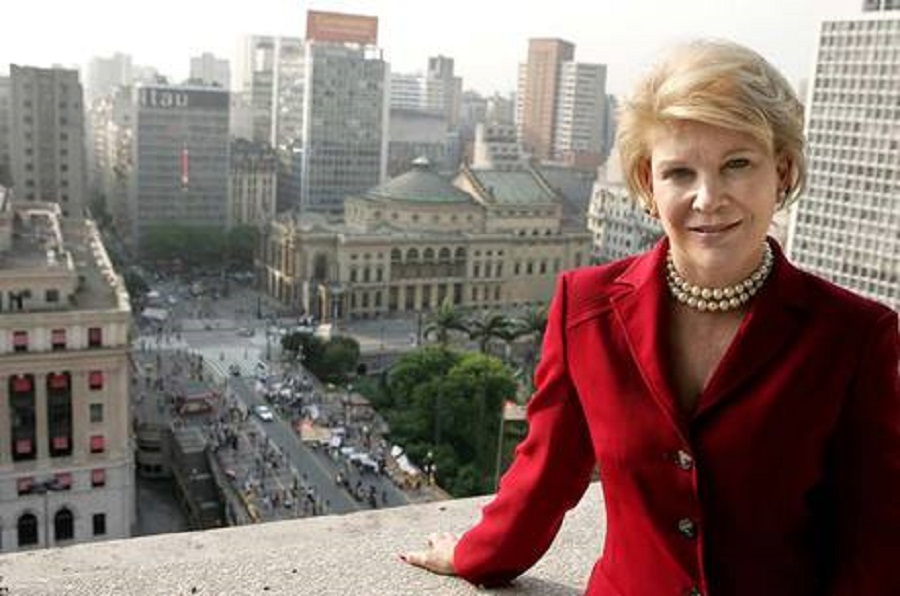

RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – It may not seem like it, but the city of São Paulo, a concrete megalopolis, has 40% of green cover, according to the city’s Secretary of International Relations, Marta Suplicy.

Much of this cover is owed to the preservation of 25,000 hectares of Atlantic Forest, equivalent to one-sixth of São Paulo’s territory, in the subdistrict of Parelheiros, in the south zone. “We are not a gray city,” says Suplicy, its mayor between 2001 and 2005.

Reversing the image of a concrete jungle is part of a city plan to embrace the green economy. “The future of cities is here,” the Secretary says. “And there is money to be sought out there.”

This will not be an easy task. São Paulo has long lived with a multitude of environmental issues, from the pollution of the Pinheiros and Tietê rivers, to the invasion of protected areas.

But, according to Suplicy, Mayor Ricardo Nunes is sure that he will have something to show at COP26, the United Nations Climate Conference, to be held in November in Scotland. The City Hall will send a committee to the event.

Climate Change Secretary Pinheiro Pedro recognizes that the city’s relationship with the environment has never been harmonious. “For a long time now, the people of São Paulo have been fighting nature,” he says. The clearest example of this conflicting relationship is in the floods. São Paulo was built on top of rivers, which today are channeled. From time to time the rivers fill up and the city floods, despite all the ditches built over the course of several administrations.

One of the initiatives taken by the city government is the construction of “rain gardens,” green areas planned to absorb the water from storms. “The goal is to increase the city’s permeability,” says Secretary of Sustainable Development of the City Hall’s Secretariat of International Relations Carlos Fernandes.

Since 2017, 117 rain gardens have been built in the city, and another 12 are under construction. They are flowerbeds slightly below street level and sidewalks. Underground, a box collects the water and relieves the drainage system that disposes of the water into the culverts.

FLEET ELECTRIFICATION

The city government is also seeking to expedite the electrification of the bus fleet. Currently, just over 1.5% of the São Paulo fleet is electrified, either by battery-powered buses or trolleybuses. In the target plan delivered to the City Council by Mayor Ricardo Nunes, 2,600 electric buses are expected to be delivered by 2024. However, this goal was initially set for 2021, but postponed due to the pandemic.

São Paulo’s bus fleet consists of 14,000 vehicles, one of the world’s largest. The Municipal Policy for Climate Change, enacted by specific legislation in 2009, states that the city needs to reduce carbon dioxide emissions by half and emissions of other pollutant gases by 90% by 2028. Currently, buses represent more than half of the city’s total emissions.

However, the strategy extends beyond compliance with the legislation. “The low carbon economy is the future, we need to create conditions in the city for green businesses to establish themselves,” Fernandes says. “And there is money for that out there.”

The problem is that what any foreigner first sees when arriving in the city are the Tietê and Pinheiros rivers. São Paulo governor João Doria has pledged to clean up the Pinheiros by 2022, and this is partly a matter for the city government, since most pollution comes from residential sewage.

Doria also announced that a park will be built around the river, to be named after Bruno Covas, the mayor of São Paulo who died in May, when his deputy mayor Ricardo Nunes assumed the post.