RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Sadly, blocks will not make an appearance in Rio de Janeiro’s streets for this year’s Carnaval, which will not be held. In normal times, the fact that streets, avenues and squares have been the stage for the four most joyful days of the year for over a century has greatly contributed to the revelry.

While the city of Rio de Janeiro celebrates its 452nd anniversary, Carnaval in the Marvelous City’s streets celebrates 128 summers. The origins of its history were spurred by tensions which led to democratic meetings that attract and mingle all kinds of people behind, alongside, in front or on top of the blocks.

In 1840, Rio’s upper-class socialites began to hold Carnival balls. Inspired by European parties, they abounded in drinks and were rocked to Old Continent tunes. Meanwhile, on the city streets, thousands of revelers were engaging in “entrudo” – a Portuguese festival in which people in costumes dance and hurl lemons, flour or water at each other.

On their way to their carnival balls, Rio’s elite would parade in their luxurious garments in open carriages and cross the streets where the folk festivities were taking place. This meeting of different groups contributed to a kind of fusion. As a result, the bourgeois revelry incorporated elements of popular festivities and vice-versa.

According to some historians, the first Carnaval street blocks licensed by the Rio de Janeiro police were recorded in 1889. These blocks were the Grupo Carnavalesco São Cristóvão, Bumba Meu Boi, Estrela da Mocidade, Corações de Ouro, Recreio dos Inocentes, Um Grupo de Máscaras, Novo Clube Terpsícoro, Guarani, Piratas do Amor, Bondengó, Zé Pereira, Lanceiros, Guaranis da Cidade Nova, Prazer da Providência, Teimosos do Catete, Prazer do Livramento, Filhos de Satã, and Crianças de Família. This was a year after slavery was abolished, lending an even more liberating characteristic to Rio’s street Carnaval.

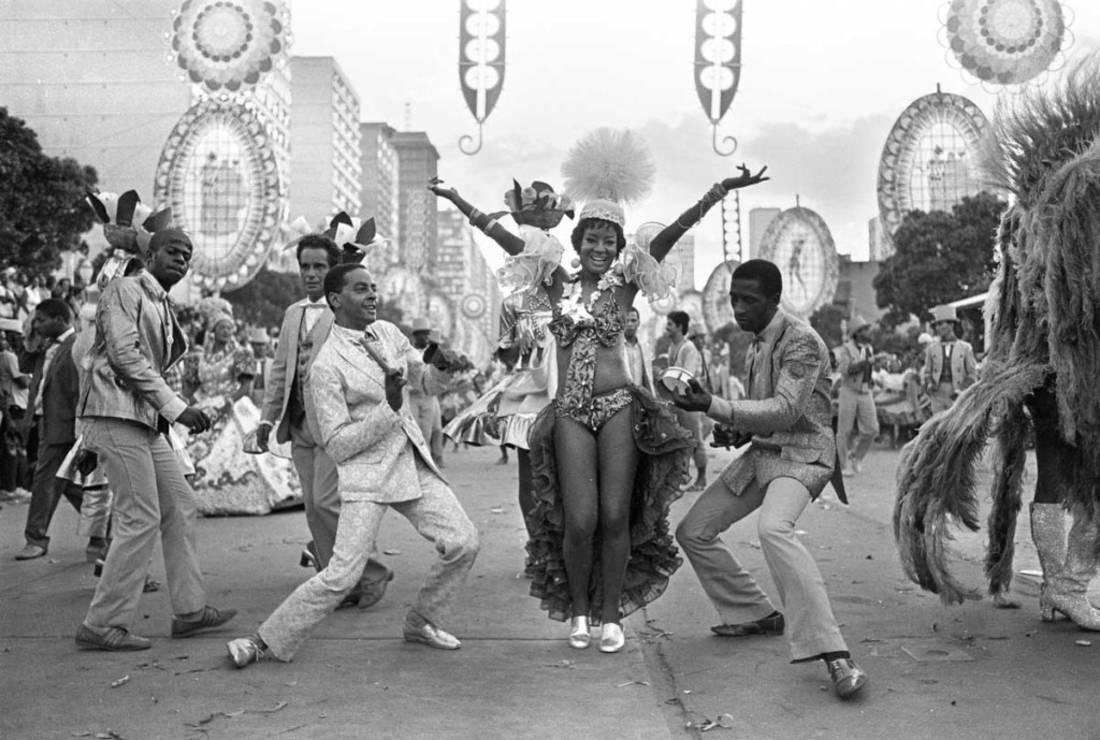

From then on, street revelry continued its course and, as a result, brought together all kinds of people in blocks featuring the most varied musical rhythms and genres. This year, some 500 blocks would have paraded in Rio de Janeiro.

In the past ten years, with the unprecedented growth in numbers of smaller street blocks and the consolidation of more traditional ones, the rhetoric that emphasizes a “resumption” of street Carnaval after years of somnolence has been adopted by many. However, this statement displeases some historians who claim “Rio’s street Carnaval has never ceased to exist.”

“In the north zone, for instance, residents place their chairs on sidewalks and dress their children for confetti battles and other activities. The Clovis have always been present in the west zone. To speak of reviving it is a somewhat narrow perspective,” says historian Luiz Antonio Simas, who is currently a consultant for the Museu da Imagem e do Som (MIS) in Rio de Janeiro. Simas goes on to reflect on the historical connection the four Carnaval days have with the city:

“It should be recalled that Carnaval, for a part of Rio de Janeiro residents, has always been a time to subvert their stolen citizenry. We created the city denied in the powerful offices in the streets, particularly in the context of a transition from slave labor to free labor, in the last years of the monarchy and the first years of the republic, when the festival gained more pronounced popular features and a significant part of it became a means of expression for the descendants of slaves. From then on, the festival became intertwined with the city’s own history, as it still is today. “Entrudos”, floats, confetti and flower battles, “arenga” blocks, “rodas de pernada” dancing, “ranchos”, “cordões”, large societies, costume dances, samba schools, “onças do Catumbi” and “caciques de Ramos”, “simpatias” and “suvacos balzaquianos”, suburban “bate-bolas” and century-old “bolas pretas”, are clues to understanding how social tensions – disguised or exacerbated in festivals – weave the history of this terreiro de São Sebastião/Oxóssi.”