RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Jair Bolsonaro has never concealed his contempt for the current composition of the Federal Supreme Court (STF). During his campaign, he said he could expand the number of justices from 11 to 21 in order to appoint “ten impartial members” to the Court.

Once sworn in as President of the Republic, he took part in a rally outside Army headquarters in Brasilia, where those attending, among other protests, called for the closure of the STF. In a remarkable incident, when prevented from appointing Alexandre Ramagem as director-general of the Federal Police, which he described as undue interference in the government, he considered disrespecting the judicial ruling and shouted, angry and ominous: “It’s over!”

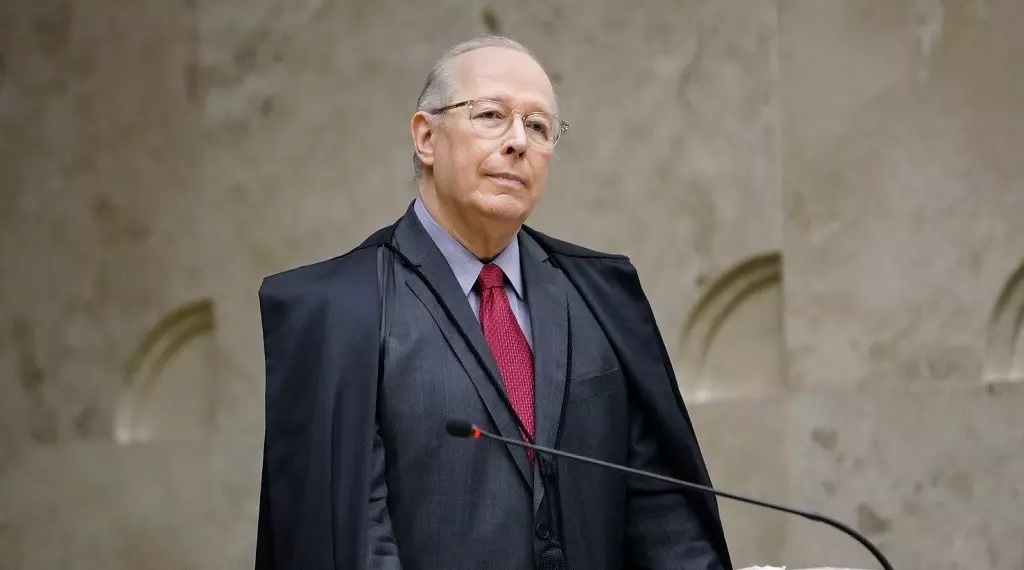

The times of explicit belligerence were (fortunately) left aside, but not the plans to change the highest Court of Brazil’s Judiciary. With the retirement of Justice Celso de Mello on October 13th, Bolsonaro has made his first appointment to the STF. The chosen appointee is federal Judge Kássio Nunes Marques, 48, who was not on anyone’s list of favorites.

The surprise came on multiple fronts. According to the President, his priority was to appoint someone with a conservative profile, capable of defending positions dear to Bolsonarism on issues such as abortion and weapons. In fact, the plan is much more comprehensive.

In the words of one of the president’s most important assistants, the appointment concerns the very future of the government: “Today, Bolsonaro’s largest opposition group is the Supreme Court. One must have someone who can put a brake on this excessive activism. Someone who has both the support of the political class and the respect of peers to balance the legal discussion, to promote technical confrontation. The justices’ tendency to speak beyond the record is unbalancing the Republic. Some behave more like political officials than like magistrates.”

And who would be the candidates to fulfill this mission? “The president had four or five options. The ideal is someone with Barroso’s profile. He is intelligent and engaging. But he overturns the law, he doesn’t do the constitutional control as he should and he legislates as if he were Parliament itself,” says the same assistant.

Appointed to the Supreme Court by then-President Dilma Rousseff, Justice Luís Roberto Barroso is known for his ability to form opinions in and out of court. He voted for the decriminalization of marijuana for personal use and for the decriminalization of abortion up to three months of pregnancy, measures that are rejected by most Bolsonarists.

What Bolsonaro refers to as a progressive agenda has, in fact, progressed in the STF. Over the past ten years, the Court has sanctioned civil unions between same-sex individuals, abortion in cases of babies with brain malformation, the validity of racial quotas in universities, and the criminalization of homophobia. All of which, for progressives, represent major civilizational advances. With the appointment of replacements for Justice Celso de Mello this year and Justice Marco Aurélio Mello next year, the President wants to swing the pendulum the other way. His way.

“Left-wing legislators have been using the Supreme Court for years, and continue to use it as a political tool because they know its progressive positions. They mainly judicialize conservative agendas by creating a shortcut, in order to immobilize Parliament, as occurred in the case of same-sex marriage,” says federal deputy Marco Feliciano (PSC-RJ), a pastor, a friend of the President and leader of the Evangelical backbenchers.

When the debate about the Supreme Court’s succession began early this year, the president said he could appoint a “terribly evangelical” name to the post. His second Minister of Justice, André Mendonça, a Presbyterian pastor, was among the betting favorites. Other names mentioned included Federal Prosecutor General Augusto Aras, Secretary-General of the Presidency Jorge Oliveira, Federal Appellate Court Judge Thompson Flores, and Superior Labor Court Chief Judge Ives Gandra Filho.

The Constitution demands only that the nominee be between 35 and 65 years of age, with outstanding legal knowledge and an unblemished reputation. It should not be difficult to find someone meeting such requirements. Last week, the dark horse emerged: Judge Kassio Nunes Marques, of the 1st Region Federal Appellate Court (TRF-1) in Brasília. On Tuesday, September 29th, Bolsonaro and Nunes visited the home of STF Justice Gilmar Mendes to notify him that the Judge would be Celso de Mello’s replacement.

The meeting was organized by Davi Alcolumbre, president of Senate president, which must approve nominees to the Supreme Court. Also present at the meeting at Mendes’ home were STF Justice Dias Toffoli and the Minister of Communications Fábio Faria. Meeting participants told VEJA magazine that Nunes Marques had been highly appraised to wear the robe at the Supreme Court. The peculiar aspect is that his initial intention was to be promoted to the Federal Superior Court (STJ), Brazil’s second-highest court.

His easy talk and the sense that he now has a firm commitment to conservatism pleased the President. “After being appointed, he will take a “pummeling” for ten days. Let’s see if he can handle it or not,” says a Minister who closely followed the negotiations. The (rhetorical) beating, of course, came swiftly. The next day, some of Bolsonaro’s allies sent the President a brief – along with a note saying “be advised” – containing purportedly disappointing information about the Judge.

The report mentions his personal relationship with the governor of Piauí, Wellington Dias of the PT (Workers’ Party), and recalls that Marques was appointed to the TRF by then-president Dilma Rousseff (also PT). For the report, Nunes must wear the PT red shirt. Bolsonaro, however, disregarded the missive from the palatial viper’s nest.

The reason is straightforward: the “pummeling”, so far only mild and above the belt, was offset by public displays of support for the Judge. In addition to endorsement by Justices Mendes and Toffoli, Marques was applauded by the so-called Centrão, the party bloc known for offering support to whichever president is in office, in exchange for positions and other benefits – not always licit.

Among this huge group are the Republicanos party evangelicals, passionate advocates of conservative agendas, and the PL (Liberal Party), several of whose members were involved in the Mensalão kickback scandal. Senator Ciro Nogueira (PP-PI), head of the political party with the most politicians investigated under Operation Lava Jato, has celebrated on social media the prospect of his fellow Piauiense joining the Supreme Court.

Nogueira and other governors argue that if the judge, who became a judge after years of practicing law in the Northeast state of Piauí, were appointed, the President would again be giving a favorable nod to Brazil’s Northeast, and thereby move a step closer to reelection.

Re-election aside, the celebration occurred for other reasons. The Centão was particularly pleased to know that Marques is not a Lava Jato advocate. Rather, he is known as a “guarantor” magistrate, who chooses to close ranks against what critics refer to as arbitrariness committed by the Lava Jato task force.

“The President wouldn’t choose a Lava Jato advocate. If that were the criteria, he would have chosen Marcelo Bretas,” says one of Bolsonaro’s aides, referring to the Lava Jato judge in Rio de Janeiro. “The senators are euphoric. Everyone liked the name. The President wanted to please politics and the Supreme Court.”

A Supreme Court justice is, naturally, quite powerful. But the power of Bolsonaro’s nominee will be tremendous. He may even indirectly influence the outcome of the upcoming presidential elections. Celso de Mello’s replacement will probably inherit Celso de Mello’s tie-breaking seat on the court’s five-seat Second Panel, now split 2-2 on votes in several Lava Jato lawsuits, including a crucil one that may decide whether ex-Judge Sérgio Moro was biased in convicting ex-president Lula in the Guarujá Triplex lawsuit.

This is an action of great interest to Bolsonaro, who sleeps, wakes, and breathes thinking about 2022. A potential favorable decision for Lula would lead to the reversal of his conviction and could ensure his ability, albeit temporary, to run for office. “Having Lula as an opponent would not be a bad idea. The election would again be polarized, and we would win with more ease than in 2018,” says a Cabinet Minister. Therefore, a decision against former Justice Minister Moro, now a political rival more feared by Bolsonaro than Lula, seems a very likely scenario.

In seeking a conservative for his first appointment to the Supreme Court, Bolsonaro, in a sense, once again mirrors US President Donald Trump. To replace Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg, an icon of the struggle for minority rights, who recently passed away, Trump appointed ultra-conservative federal Judge Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court. “The Supreme Court will decide on the survival of the Second Amendment, which guarantees the right to have weapons, our religious freedom, our public safety, and much more,” Trump said. “There’s no one better to do this than Amy Coney Barrett”.

America’s highest court has nine Justices with lifelong tenure. Senate confirmation of Barrett’s nomination, the target of protests from the Democratic Party for having occurred just before the November presidential elections, would enable the conservatives to expand their current 5-4 majority to 6-3.

A worthy disciple, Bolsonaro wants to clone this proceeding here. According to Rubens Glezer, a professor at the Getúlio Vargas Foundation’s School of Law in São Paulo, the Brazilian chief executive has a greater chance of influencing the balance of justice with his appointment than does his American counterpart, since the legal culture of the United States respects case law precedent (“stare decisis”) more than does the STF.

There, SCOTUS Justices give greater consideration to judgments handed down in the past than to their own consciences. Most Brazilian magistrates judge according to their own personal principles, notwithstanding existing case law, ofttimes not weighing the consequences of their decision on legal stability, explains Glezer. On this STF trend, he adds that in Brazil Justices, when taking on the role of case rapporteur, feel as if they “own” it and are entitled even to prevent the full Court from reviewing their monocratic decisions. In theory therefore, a Justice Nunes Marques could help, more proactively, to implement an agenda based on the President’s interests. “Hence, Bolsonaro’s choice has much more institutional and cultural weight over our society than that of President Donald Trump.”

Not only the Supreme Court rulings regarding customs or Lava Jato displease Bolsonaro. The President complains of orders and demonstrations by the Court’s Justices which, according to him, are purely politically motivated. When he is in a good mood, Bolsonaro claims that the STF misuses its jurisdiction. When he wakes up feeling radical, he overreacts and thinks that the Court wants to overthrow him. Hence the decision to appoint someone considered of his utmost trust. Someone, as he himself said, with whom he can enjoy a beer over the weekend.

It is Brazilian political tradition that godfathers expect gratitude and loyalty from their protégés. Fortunately, history shows that the system does not always work that way. Justices appointed by PT voted to convict party leaders in the Mensalão case. Joaquim Barbosa, Luiz Fux, Roberto Barroso, to name a few, did not line up with the PT or leftists after their appointment. Quite the opposite – they were often harsh with the party that placed them there: “The position is for life, and it is the justices’ biography that becomes relevant, not who appointed them,” says Ricardo Ismael, a political scientist and professor at PUC-Rio.

In the military dictatorship, then STF Justice Victor Nunes Leal already talked about the presidents’ frustration at seeing their nominees take their own stand after being sworn in. “A ruler who was not disappointed is hard to find, by selecting respectable and honorable people, expecting them to be his spokespeople in Court,” he said, referring to the intention of Marshal Castello Branco’s government to redesign the Court’s composition by increasing the number of seats through an Institutional Act.

If he is indeed confirmed as STF Justice after undergoing confirmation hearings in the Senate, Judge Kassio Nunes Marques, unknown today, will certainly join the ranks of national celebrities.

Nowadays most Brazilians do not know who the eleven members of the Brazilian national soccer squad are, but they know the identities of the eleven justices of the highest court in the country. Justice Barroso is sometimes applauded while on flights or in restaurants; conversely, Justice Gilmar Mendes, who takes bold positions against public opinion, is often booed in his wanderings around Lisbon, where he has a home. He doesn’t care.

No matter what position he takes on abortion, drugs, homophobia, Lava Jato, or elections, Kassio Marques will not go unnoticed or be ignored. He will act directly on – and help write – the history of Brazil. May the Judge understand this tremendous responsibility and live up to the magnitude of his mission.

Source: Veja