RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Bonde dos Cachorros is not a funk group, Amigos do Estado is not an NGO that partners with the Government, Sindicato RN does not defend any professional category and ‘Cerol Fino’ is not a kite club. These are the names, unknown to many, of some of the dozens of Brazilian criminal factions that help to make up the complex scenario of drug trafficking and robbery in their states (Pernambuco, Goiás, Rio Grande do Norte, and São Paulo respectively) and in the country.

In the shadows of larger groups such as the Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC – First Capital Command), Comando Vermelho (CV – Red Command) and Família do Norte (Northern Family) – and often forming alliances with them – these factions compete for their share of the lucrative business of selling cocaine, marijuana and crack in prisons and peripheral areas throughout the country.

The growing strength of these smaller groups becomes clear when examining faction recruitment within the federal prison system, with five maximum-security facilities throughout the country. In these penitentiaries where there is no overcrowding – an occupation rate of 70 percent of just over 800 places is estimated – there has never been an escape since the first unit was inaugurated in 2006.

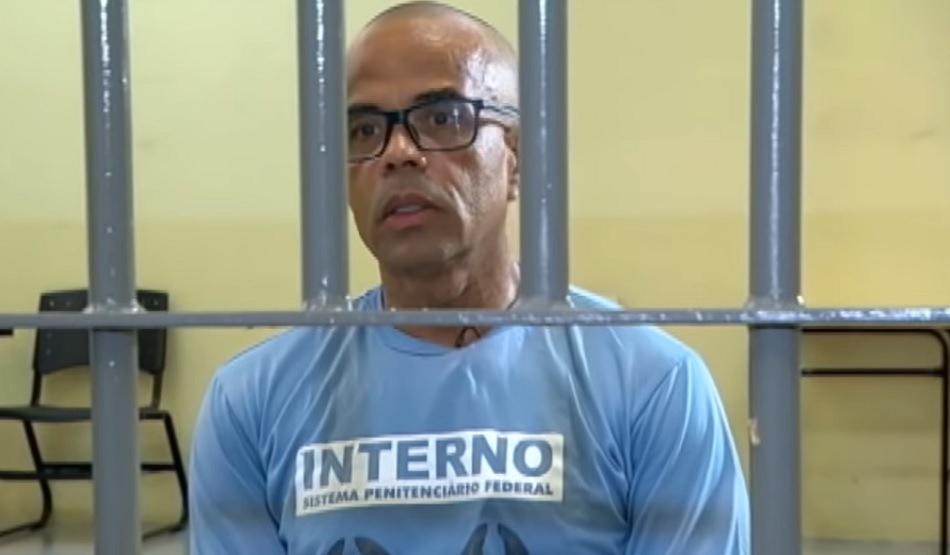

These penitentiaries are home to the most dangerous inmates, those with the potential to disrupt facilities run by state governments, or who have continued calling the shots in the criminal world while behind bars. Fernandinho Beira-Mar (CV), Nem da Rocinha (Amigo dos Amigos), Marco Willians Herbas Camacho, Marcola (PCC) and José Roberto Fernandes Barbosa, aka Zé da Compensa (FDN), are some of the inmates at the federal level, which have also sheltered brothers Gerominho and Natalino, founders of the Liga da Justiça militia.

Now these notorious prisoners are joined by inmates from at least 30 factions and militias from virtually every state in the country, according to information from the National Penitentiary Department, linked to the Ministry of Justice and Public Safety. These include Os Manos, Os Abertos and Tauras factions from Rio Grande do Sul, the Massa Carcerária from Rio Grande do Norte, Primeiro Grupo Catarinense, and Primeira Guerrilha do Norte, from the state of Pará, among others.

However, the total number of factions in the country is probably greater than reported, as some of them (such as Unidos pela Paz and Comando Pelo Certo from Rio Grande do Sul) have no representatives in the federal prison system. “Caution must be exercised when considering these figures. We cannot say that these are the national groups. The two national factions, present in all states or in most of them, are the CV and the PCC,” says sociologist Gabriel Feltran, author of the book ‘Irmãos, Uma História do PCC’ (Brothers, A History of the PCC).

Despite the existence of dozens of rivals, the Primeiro Comando da Capital, the largest Brazilian faction with an international presence in other South American countries, is the group with the largest number of prisoners in the federal system: there are 204 members within a population of just over 640 prisoners, followed by Comando Vermelho with 126 prisoners and the Familia do Norte with 50; the fourth and fifth ranking are Guardiães do Estado (Ceará) with 22 members and Nova Okaida (Paraíba) with 14.

The low rate of incarcerated militia men is striking. These paramilitary groups from Rio de Janeiro, which are largely made up of former law enforcement agents, are identified as one of the greatest threats to democracy in Rio de Janeiro, controlling territories in which more than two million people live. Extortion, murders, control of clandestine transports, and even the sale of drugs, are just some of the areas in which these criminals operate. But one of the greatest risks of the militiamen’s actions is their successful incursions into politics, electing legislators and city councilors, in addition to getting positions in offices like that of today’s Senator Flávio Bolsonaro.

However, only 12 militiamen are currently being held in the federal system. Two of them are part of the Escritório do Crime (Crime Cabinet), a criminal group allegedly led by former BOPE (tactical unit of the Rio State Police) Adriano da Nóbrega, who died in Bahia on February 9th during police action.

The Crime Cabinet is suspected of having a hand in the death of Rio city councilor Marielle Franco and her driver Anderson Gomes in March 2018, a murder that has not yet been fully clarified. Two other prisoners are part of the legendary Liga da Justiça (Justice League), now commanded by Wellington da Silva Braga, aka Ecko, and considered one of the largest in Rio with a strong presence in the western part of the capital and in the suburban Baixada Fluminense town. A member of the Jacarepaguá neighborhood militia in Rio is also in the federal system, along with seven “former public safety agents” who figure in the DEPEN (National Penitentiary Department) listing with no details regarding the group to which they belong.

The Primeiro Comando da Capital and the Família do Norte were the factions that “had the most members sent to the federal prison system in recent years, mainly due to the crisis in the prisons of Manaus in 2019 and also due to the transfer of the PCC leadership,” the DEPEN reported in a statement. In February 2019, more than 20 PCC inmates, including group leader Marcola, were sent to the federal system at the request of the São Paulo Prosecutor’s Office after an agreement between the state and federal governments. The goal of the transfers was to undermine the communication and command network that the group had set up in the state penitentiary in Presidente Venceslau, 610 kilometers northwest of the São Paulo capital. In addition, plans were uncovered for the assassination of anti-organized crime prosecutors that would have been devised by some of these inmates.

With the PCC and the CV growing and expanding their activities, it is up to the other groups to change their strategy in order to survive. “When these factions [PCC and CV] expand, following these market trails [trafficking routes, market, and drug suppliers], the local drug trafficking and robbery groups are faced with ‘outsider’ groups coming into their territories with greater experience and significant mercantile advantages by controlling the market chains. If they want to retain control over their territories, either these local groups join forces with each other, or with a national faction, or confront them,” Feltran explains.

The multiplication of local factions in some states may lead to the reorganization of crime structures in the region, with the clustering of dispersed groups into a new one to counter the common enemy. In some cases this criminal rivalry is even present in the name chosen: in Paraíba, the Okaida (inspired by the name of the terrorist group Al-Qaeda) was first created in the early 2000s. In order to face it and remain on the map, the remaining gangs grouped together in a faction named the Estados Unidos. In Rio Grande do Sul the ‘Bala na Cara’ (or ‘Toma Boca’ as they are known by their rivals) confront a faction created from the multi-group coalition called Antibala-V7.

The federal prison system holds a distinguished international inmate: José González Valencia, 43, aka El Chepa or Camarón, leader of Mexico’s Jalisco Nueva Generación (or Jalisco New Generation) cartel, the country’s second-largest behind the Sinaloa group. He is considered by authorities to be the organization’s financial operator, and was arrested in 2017 in Fortaleza while on vacation with his family. The US and Mexico are fighting for his extradition, which now has a favorable ruling from the Office of the Prosecutor General, and is pending a Supreme Court decision.

The federal system’s sentence enforcement is harsh: 22 hours locked up in the cell (no TV in most units) and two hours in the sun. Visitors and attorneys are controlled by means of body x-ray systems to prevent cell phones, drugs, and weapons from entering, which is common in state prisons. According to the DEPEN, these strict protocols are responsible for the absence of “disruption of order or rebellion” in the facilities. In addition, “no cell phones or banned equipment have been found” in these penitentiaries, according to official data.

The organization and professionalization of criminal groups is not new: “Internationally, this process has occurred in recent decades, since the success of the Colombian cartels of the 1980s, which expanded the cocaine markets and their astronomical profits through several poor neighborhoods in Latin America,” says Feltran, who also cites as an example criminal groups that operate in Mexico, Central America, and northern Argentina. “Small criminal groups, typically local gangs, are gradually becoming larger and more professional. In some cases, these groups originate from law enforcement, in others from prisons, in others among paramilitary groups, but both regulate or control very lucrative illegal markets.

Over 40 years after the creation of Brazil’s first faction, the Comando Vermelho, founded in 1979 within the Ilha Grande penitentiary in Rio de Janeiro, this criminal group model, based on the dominance and recruitment of members within prisons, continues to find fertile ground here. Several factors contribute to this: a considerable internal market, public security policies focused almost exclusively on repression, and an important role as an international trafficking route to Europe and Africa, channeling the drugs produced in Bolivia, Colombia, Venezuela, and Paraguay. All of this makes Brazil the country of choice for many factions.

Source: El País