RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – (Opinion) It has certainly been easy to trash Brazil lately. It seems to have become a mini-industry for the world’s media.

The NYTimes, the Economist, and many others have focused on what’s wrong with the country: its exploding Covid-19 cases; its cavalier, reckless, hapless and now Covid-19 infected president; its depressed economy; its Amazon fires claiming and destroying more and more of what is called, rightly or wrongly, ‘the lungs of the planet’; and its criminal disregard for indigenous people.

One hears with increasing regularity tired old one-liners like “Brazil is the country of the future and always will be.” I think it’s time to push back.

You can always tell when a Latin American crisis story is getting through. Gringos like me notice an increase in the messages from friends and family abroad asking when I’m coming ‘home’. When am I going to jilt my love affair with Brazil and ‘get wise’? Obviously unmoved by the US’s descending position in the world order and its well-documented discontent, they have trouble believing that ‘home’ can be anywhere other than the ‘good ole USA’.

Decrying its fall from leadership, Nobel economics laureate Paul Krugman wrote recently; “I don’t think any other advanced country (but are we still an advanced country?) has a comparable number of people who respond with rage when asked to wear a mask in a supermarket. There definitely isn’t any other advanced country where demonstrators against public health measures would wave guns around and invade state capitols.”

There have been, and continue to be, large and mostly peaceful demonstrations in Brazilian streets, although many people, sensibly eager to avoid crowds and possible virus infection, have stayed away, reducing their size. These are not principally demonstrations of unity with the Black Lives Matter movement, but rather about the Brazilian government’s copy-cat failure to give leadership in battling corruption and the pandemic.

Feelings supporting BLM are strong here, but unlike the US, black and multiracial people in Brazil do not see themselves as a united ethnic group easily identified under the BLM banner, but rather as much more loosely defined cohorts.

Research from LABS (Latin America Business Stories) reported: “In 1976, when census researchers asked citizens to describe their own skin color, without any options to choose from … the thousands of Brazilians surveyed gave the researchers a list of 136 different colors, ranging from ‘coffee,’ ‘cinnamon’ and ‘honey’ to ‘toasted,’ ‘singed’ and even ‘wheat’.” Brazilians don’t take themselves too seriously and poke fun, not assault rifles, at bureaucrats.

The problem with all the media trashing going on is that ‘bad’ news always gains more viewers and readers than ‘good’. It’s too easy to downgrade a country based on rotten leadership. There are always other, perhaps less visible, aspects that deserve consideration. One way or another, Brazil has developed a vibrant culture as diverse as its people.

Seen from the perspective of a ‘foreigner’, albeit one who has lived here for more than two decades, Brazil’s ‘soft’ assets should be valued as highly as, or higher than, its ‘hard’ liabilities.

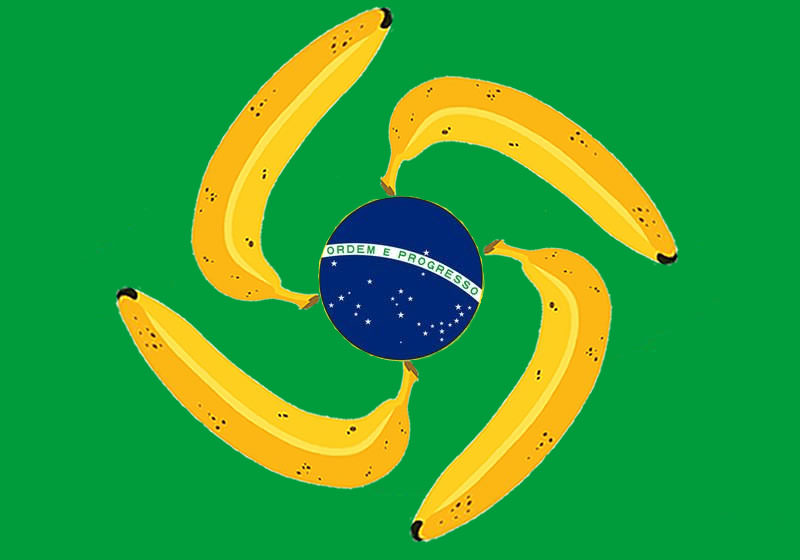

When a Brazilian friend was asked smugly, by one of my visiting countrymen, why he would chose to live in a ‘banana republic’, he answered without hesitation: “Because the bananas are so good.” At first glance that may seem a decidedly facile response and a false equivalence, but it highlights what is really important to Brazilians and what isn’t.

Bananas are just one of the soft assets. So are the delicious fresh pineapples we eat every day, unrecognizable when compared with those perfectly rounded, almost tasteless slices out of the Dole can, a feature of my childhood tasting more like plastic than the real thing. That fresh taste is true of almost everything we eat, one reason why even in the current economic doldrums, Brazilian agriculture, a massive contributor to the Brazilian economy, is booming.

It’s not highlighted in large type on Florida orange juice labels or in stories about Brazil’s difficulties (although perhaps it should be) but “more than 50 percent of all orange juice bottled by major companies like Tropicana is supplied by a Brazilian company, shipped in specialized fruit juice tankers from the Port of Santos in Sao Paulo. In 2017, this OJ export market was worth $1.4 billion.”

That’s not peanuts (to mix a metaphor). Add soybeans, corn, wheat, sugarcane, and coffee plus beef and pork products and the sector is something to reasonably brag about. So too is the high level of technological support for developing new types of seeds and advanced agricultural processes.

In my experience, most Brazilians are not often braggarts; they tend to understate rather than overstate. What’s more important to them than kudos is the joy of living. They measure wealth more in pleasure than monetary value and material acquisition. They are mostly happy and rate higher on the world happiness index than the US, which enjoys (or is that the right word?) hugely greater prosperity.

What gets all too little mention in the popular Brazil-bashing commentary is the Brazilian ‘happiness quotient’, that special human quality of the population which has a very positive outlook, no matter how poor the present climate. Unfortunately, happiness doesn’t often make headlines.

Returning from the US many years ago, Antônio Carlos Jobim, the godfather of bossa nova, was asked how he felt coming back to Brazil. His answer sums up something detractors should try to understand: “To live in other countries is great, but it’s shit. To live in Brazil is shit, but it’s great.”