RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – “In Venezuela one lives a genuine freedom.”

With this sentence, the Spanish newspaper El País began its 1976 article on the thousands of immigrants from dictatorial regimes in South America, and even from Spain itself, who were seeking a safe haven in Venezuela to prosper.

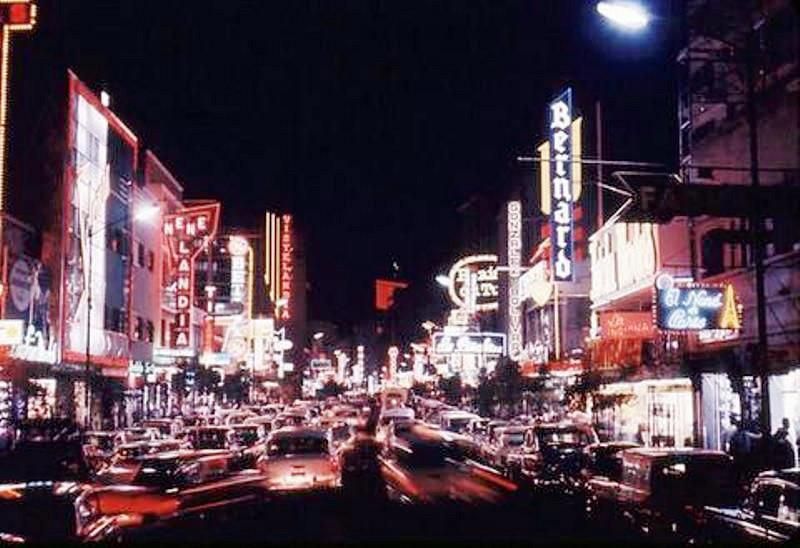

It was also around that time that Venezuelans became known in Miami as the “da-me dos” (give me two), in a joke about how cheap the products seemed in relation to their income.

Reports of the country’s prosperity were plentiful. Alexander Guerrero, a university professor who emigrated from Spain to Venezuela in 1978, said with his first salary of US$1,700 (twice the annual per capita GDP in Latin America at the time), he was able to buy his first car. Today, his salary would be about US$35. It would be, that is, if he had not moved to the United States.

With the 4th highest per capita GDP on the planet in the 1950s, Venezuela seemed at last to have found the missing element in its troubled history: democratic stability.

In fact, for at least three decades, this combination of a prosperous country, with abundant oil wealth and social stability, promoted profound changes, notably in education and in the fight against poverty, which by the end of the 1970s had reached less than 15 percent, about half of Brazil’s index at the time.

However, this is not the tale of a country where everything was fine, until by a fateful misfortune it underwent the Bolivarian revolution and its 21st century socialism, the disastrous results of which make Venezuela today the poorest country in South America, with 87 percent of its population living in poverty.

To be accurate, one must realize that the problems started with Bolivar himself, the national hero who freed Venezuela and five other countries from Spanish domination, and who today is best known for being part of the team that gives its name to the main soccer competition in the Americas, the Libertadores (among whom are also Don Pedro I, San Martín, Sucre and others).

If, for Venezuelans, Bolivar is a kind of “George Washington of the South,” in reference to the father of the independence of all 13 colonies that would comprise the United States, for other countries, Bolivar is exactly the opposite. For Peruvians, for instance, he is a kind of dictator.

Made independent in 1821 by San Martín, the Argentinian who also promoted the independence of his native country, Peru was ruled by Bolivar between 1824 and 1826. In this brief period, he forced the country’s congress to elect him dictator, repealed the release of slaves promoted by San Martín and also introduced a “tax on indigenous peoples”.

The son of the Creole elite, the Spanish colonial elite, Bolivar never denied his authoritarian slant. Unlike Washington and the revolutionaries of the 13 colonies, the concern with centralizing power has never been on the agenda in the independence processes of the region.

Ironically at the time, Bolivar resembled Napoleon, who, by invading and “freeing” European countries, and spreading the French revolution, handed over to his own people the command of such countries, like Spain, where José Bonaparte would rule in his brother’s name.

Of course, irony may not be exactly the word. After all, as Gabriel García Marquez recalls in “The general in his labyrinth”, the aristocrat Bolivar, who studied in Europe, attended the inauguration of the short Corsican, the Emperor of the French, Napoleon Bonaparte.

Whether for the brevity of Bolivar’s rule, having died at the age of 47 after being head of 6 different nations in South America, the fact is that Venezuela, like other countries in the region, was born ruled by the same local elite, heir to the former metropolis.

Its institutions were what economists like to call “extractivist institutions” when a small group takes over the central power of the state and uses it to extract the maximum possible benefits for itself.

Not by coincidence, Latin America, where these institutions are abundant, is the stage of countless coups d’état and other financial catastrophes.

Taking possession of the state, this elite takes over the tax collection means, and uses it for shady ends. Venezuela is the country with the second-highest number of defaults in history, with a total of 12 (compared to ten in Brazil and nine in Argentina).

These groups act in a similar way by targeting the best lands for themselves, and establishing ways to ensure that they are well protected with property rights denied to the majority of the population.

Whether in Argentina, where the state auctioned public lands to large landowners, or in Brazil, where Eusébio de Queiroz, one of the leaders of the Conservative party and responsible for the law to free the children of slaves, created the “Land Law”, which prevented immigrants from buying property in the country, forcing them to work for local farmers, the practice is common.

Also common, the exclusion of access to education pervades all countries in the region that embrace such institutions. Brazil only achieved universal education in the 1990s, and even today almost one in six youths drop out of school.

What distinguishes Venezuela in this tale, however, is its great opportunity, and, once again, its mistakes and historical issues have paid their price.

In April 1914 the country found oil. In 1920, laws were created establishing royalties and government participation in export revenues. In 1928, nine years before Brazilian author Monteiro Lobato released his “The well of the viscount” and began his crusade in search of oil in Brazil, Venezuela was already exporting 275,000 barrels a day.

For the next six decades the country would become a “Saudi Arabia of the Americas”, in reference to the country governed by the Saudi monarchy, the world’s largest oil producer.

Venezuela’s economy grew, outperforming neighboring countries and reaching high levels even for countries considered wealthy. Such wealth has attracted the attention of politicians, amplifying the historical problems.

However, in 1958, dictator Marco Pérez Jimenez was ousted in the 7th coup d’état in the country’s history (among a total of 11, counting both successful and unsuccessful ones), making way for the Fourth Venezuelan Republic.

By then, the country was already accumulating wealth and was striking by its disparity with other countries on the continent. However, all this growth was exclusionary, with high poverty rates. It was precisely because of this that the central goal of Venezuelan democracy would become, in the years to come, the redistribution of income.

The country’s economic openness, which had led to foreign investment, had not been enough to ease social issues. Moving in the opposite direction, the government promoted the nationalization of oil production in the 1970s.

Amid the global shock, with the 1973 crisis, prices skyrocketed, and wealth increased. But so did public spending. Pharaonic projects are erected, dramatically raising the public debt.

In its eagerness to superficially correct the country’s social ills, the democratic regime ignores its dependence on oil, expands its bets on the sector, and thereby, albeit with greater benefits for the population, keeps most of its institutions virtually unchanged.

There is no attempt to placate the social issues, an improvement in order for the business environment to become favorable to diversifying the economy, and of course, there is also no concern with “saving”.

The Venezuelans, intoxicated by whisky consumption, which by then had become the largest on the planet, topping Scotland, were not even close to creating a kind of “sovereign fund”, as Norway later did, to save resources and safeguard the country’s economy from the dollar flood.

For economists, the symptomatic name is “Dutch disease”, or in short: when a single economic sector becomes so dominant that taking other paths becomes nonsensical.

For every US$100 that entered the country, US$95 came from oil. To make matters worse, the resources, although abundant, were lower than what rulers were willing to spend, leading to debts.

It was then that oil prices began to drop. Between 1981 and 1983, oil exports fell from US$19.3 to US$13.5 billion.

With current spending commitments and fewer resources, the government then plunges into a negative spiral. On February 18th, 1983, occurs what Venezuelans started to call “Viernes Negros” (Black Friday). As a result of exchange controls and the end of the gold standard, the Bolívar exchange rate melts.

The country will become part of the “lost decade” team, as the Latin American countries that suffered as a result of the drop in commodity prices and the increase in debt became known (such as Mexico, where the term originates, or Brazil and Argentina).

In this chaotic scenario emerges Hugo Rafael Frias Chávez and once again, as on Groundhog Day, vows to compensate the excluded population with oil resources. Like Bolivar, or Napoleon, he allots the state and drains the coffers of PDVSA, the country’s state-owned oil company.

It takes no more than a paragraph to illustrate the resounding failure of 21st century socialism and the Bolivarian revolution. The result, in addition to a significant increase in poverty (which, as mentioned earlier, reaches 87 percent of the population), generates anecdotal cases, such as the shortage of fuel in the country with the largest oil reserves on the planet.

However, the major challenge is understanding how not even nature’s gifts, such as the country’s abundant resources, its enormous gold and diamond reserves, for instance, withstand parasitic institutions.

The lack of long-term perspective, the contempt for responsibility, and the urgency to mitigate issues simply through redistribution, instead of creating wealth, are Venezuela’s historical traits and lessons that make it yet another sad chapter in Latin America.