RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – The shadow of the Nazi swastika is advancing in Jair Bolsonaro’s Brazil. Powered by the President’s racist, anti-communist, pro-gun and LGBT-phobic discourse, extreme right-wing and Hitler-inspired radical groups proliferate on social media, and even risk showing themselves in small groups on the streets under flags, slogans and with the occasional use of violence. The growth of this far-right strand in the country during the Bolsonaro government can be quantified on the Internet.

According to a survey conducted by Safernet, a non-governmental organization (NGO) that promotes human rights on the Internet and monitors radical websites, 204 new websites with neo-Nazi content were created in May 2020, compared to 42 in the same month last year and 28 in May 2018.

According to the organization, there is a casual relationship between what the President says and does, and this radicalization on the web. In a note, the organization stated that it is “undeniable that the repeated demonstrations of hatred against minorities by members of the Bolsonaro government have empowered neo-Nazi cells in Brazil”. The Planalto refused to comment on this data when questioned by the El Pais newsroom.

The growth of neo-Nazism in the country, and its attraction to the President, is also noted in other studies. Adriana Dias, an anthropologist at the University of Campinas, an expert on the subject, identified 334 neo-Nazi cells in activity in the country in late 2019, most of them still active today. Each cell has between 3 and 30 members, she says.

“There are groups or neo-Nazi cells that have come closer to Bolsonarism and recent street rallies,” Dias says. She notes that there are “self-styled sovereignists [linked to the soi-disant philosopher Olavo de Carvalho, the intellectual guru of the Bolsonaro clan], who are found in neo-Nazi cells in Paraná, the Federal District, São Paulo, and Goiânia.”

This political broth that both Safernet and the researcher point out has seen new ingredients in recent months. The most recent occurred in a pro-democracy rally held on May 31st on Paulista Avenue in São Paulo, when a group raised flags from the Pravii Sektor (Right-wing Sector) radical Ukrainian group. Days later, the President posted a video on social media with a quote attributed to the Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini: “It is better to live one day as a lion than 100 years as a sheep”.

The same quote had already been employed by Donald Trump, who is also perceived as having a dubious discourse sympathetic to North American neo-Nazi groups.

Neo-Nazis “disappointed,” but at their disposal

In Bolsonaro’s case, the President’s popularity among the far-right became clear as early as October 2018, when he won the second round vote. That month, the number of new neo-Nazi pages on social media and websites in Brazil reached 441 (up from 89 in September). According to the NGO Safernet, it was a historic peak. Bolsonaro’s victory was celebrated in several discussions in the hate forum known as StormFront.

The website, which uses the White Pride World Wide slogan, was founded by Don Black, a former member of the Ku Klux Klan – a racist group that emerged in the late 19th century in the US and is still active today, allegedly responsible for the murder of dozens of blacks in the United States. The topic titled “Bolsonaro wins Brazil” had over 7,000 views.

Most of the comments are complimentary to the “former captain of the far-right army,” as it is called by a network user. Ironically, the President is the target of criticism in the racist forum for his closeness to Israel. “I agree that it is bad on the Jewish issue, but at least he is discrediting the media and this opens the door to our movement,” wrote a Brazilian supremacist at the forum.

In a global context of increasing radicalism and xenophobia, Bolsonaro has become the chosen voice of supremacists in Latin America. “All [neo-Nazi] movements have placed their bets on Bolsonarism, and some are deeply disappointed with the President because they hoped he would impose an even greater right-wing administration: things like banning homosexuality in Brazil,” Dias says.

An even more radicalized faction, which according to the researcher would account for approximately 25 percent of Brazilian neo-Nazis, expected “a totally radical, totally ultra right-wing, and he’s flirting with it”. The President’s flirtation with ‘military intervention’ has become more common in recent weeks as the prospect of an impeachment is seen but is still unlikely to prosper in Congress.

One of the main appeals of the Bolsonarist ideology for neo-Nazis is the racial issue. The President has even been accused -and acquitted- of the crime of racism, and opposes the racial quota policies. In the StormFront radical forum, one of its users asks “what do white Brazilians get out of Bolsonaro?” Another supremacist’s answer is direct: “He said he would end affirmative action [quotas].”

This conversation exemplifies what anthropologist Adriana Dias considers a racist discourse that operates in two stages. The first is directed solely at the initiates and is explicit: it would be the blunt neo-Nazi discourse of eliminating blacks and Jews. This message would not be palatable to a larger population. A second stage of the message is introduced, which is aimed at most lay people and does not speak openly of white supremacy.

“At this stage of the discourse, for the uninitiated, it appears as ‘blacks are taking their place in the university because of quotas,'” she says. Dias is concerned about the impact that Bolsonaro’s speeches may have in empowering the far-right. “There are the [already convinced] Nazis and those who are being Nazified by a narrative that is also penetrating society through the President’s voice,” she says.

At StormFront, a supremacist explains his view of the President: “Bolsonaro is a Nazi in disguise. Nowadays nobody can be a Nazi openly, so he chose to spread white supremacy through decoy and dissimulation, as all politicians do.”

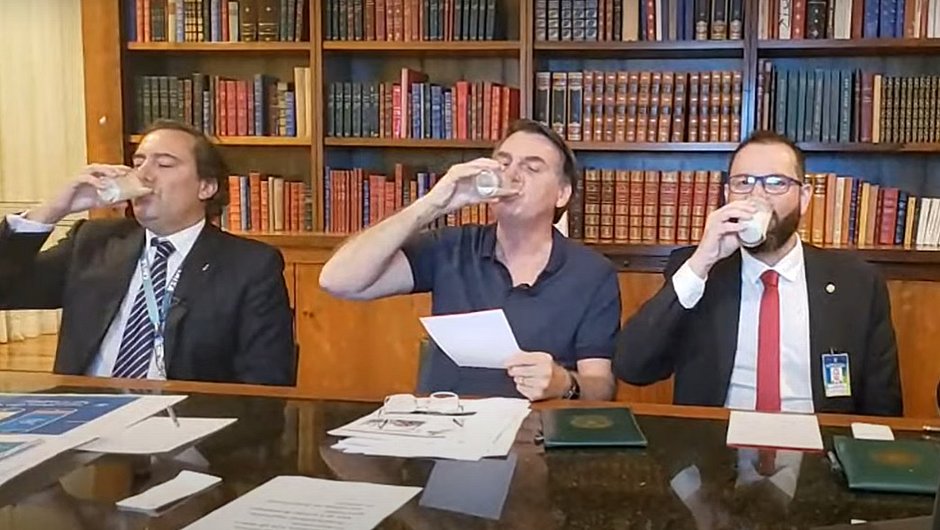

The neo-Nazi fascination with the President grows with some of Bolsonaro’s gestures, who may not even know the connection with fascism. The latest example was a toast the President made during one of his live broadcasts, using a glass of milk as an excuse to join the “milk challenge” proposed by the Brazilian Association of Milk Producers to strengthen their business sector.

A glass of milk is one of the symbols used by white supremacists, whose emoji grew stronger on radical social media to the point of replacing another neo-Nazi mascot: Pepe the Frog (a character from a comic book that became a meme and was appropriated by supremacists from 2015).

The symbolic coincidence was reinforced the next day by blogger and pro-Bolsonaro activist Allan dos Santos, who echoed the action with the drink and, amid laughter, delivered a “subliminal” message saying that “connoisseurs will understand”. Santos is now the target of an inquiry that investigates the spread of fake news and attacks on the judiciary and the legislature.

Bolsonaro and those around him have already shown that they can have some degree of mastery and familiarity with white supremacist symbols. On February 20th this year an unprecedented event occurred at the gates of the Alvorada Palace, a pilgrimage point for the President’s supporters. A supporter approaches, makes the “ok” symbol with his hand, and takes a photo with the President in the background. Typically pleasant to his voters, Bolsonaro displayed a certain annoyance and scolded the young man: “That gesture there, if it were a nice gesture, but sorry, it looks bad to me”.

What could have triggered such a reaction to a simple “ok” gesture that even prompted presidential security guards to ask for the picture to be deleted? Bolsonaro was aware of what the vast majority of the population didn’t even suspect. The “ok” sign was incorporated into the neo-Nazi gesturing to the point of being classified as a “true expression of white supremacy” by the Anti-Defamation League of the United States, linked to the Jewish community.

None of this is coincidental, in the opinion of David Nemer, professor and anthropologist at the University of Virginia. “Bolsonaro does dog-whistle politics: he uses a coded language that seems to mean one thing to the general population, but has a specific meaning for the subgroup he intends to reach. This subgroup understands the message and empowers itself,” he explains. “This far right-wing group, no matter how small a minority it is in society, contributes to the radicalization of the Bolsonarist base, which is smaller, more radical,” he says.

What does Bolsonaro gain by quoting fascist leaders like Mussolini, and using gestures that can help empower a small, radicalized sector of society? “It is not possible to understand Bolsonaro with a common paradigm in the democratic context, in which the president will do his utmost to have the support of the majority of the population for reelection. He does not operate in this logic,” says Isabela Kalil, professor of the Foundation School of Sociology and Politics of São Paulo.

“If we are looking at the standard democratic calculation, each voter is a number, one vote. In this case his logic does not operate through number of votes. It is a logic in which certain groups, even small ones, can do great damage to democracy, until they declare war on political enemies and institutions”, she says.

She mentions as an example the fact that we are having to discuss “the 300 from Brazil and the Ukrainian flags in the midst of a pandemic and without a Minister of Health specialized in the issue.” “These more radicalized groups are at Bolsonaro’s disposal. If he says ‘we are at war against such a group’, some supporters will not shy away from attacking these opponents”.

An ancient story

The affection neo-Nazis nurture for Brazil’s President is nothing new – it has more than a decade of history. In 2011, Brazilian StormFront website users even held a “civic rally” on behalf of then federal deputy Jair Bolsonaro in the MASP open air space on Paulista Avenue. “Let’s offer our support to the only deputy who clashes head-on with these libertine and communists!!”, said the call for the rally, once again establishing the link between the deputy’s anti-communism and the neo-Nazi ideology.

“The Bolsonaro factor has always been important [for Brazilian neo-Nazis]. Even before the elections, whenever he spoke of neo-Nazi groups he demonstrated on the Internet,” says anthropologist Dias. She points to the creation of the Misanthropic Brasil radical group in 2016 as an example. The group’s emergence as an arm of the neo-Nazi Misanthropic Division coincided with the rise of Bolsonaro: that was the year he announced that he would run for President. Currently, the Brazilian chapter has 147 members divided into four cells.

Some far-right-wing sympathizers have ultimately joined the government. This was the case of the then Special Secretary of Culture Roberto Alvim, dismissed in January after giving a speech paraphrasing excerpts from a message by former Nazi German propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels. “Rhetorical coincidence,” he said, not to mention the soundtrack to the video, an opera by Wagner, Hitler’s favorite composer.

At the time of the election campaign, Bolsonaro garnered the support of former Klan member David Duke: “He sounds like us. And he’s also a very strong candidate. He’s a nationalist,” he said in 2018. The bad repercussion of being associated with a former grand wizard (Duke’s position in the organization, one of the highest ranked) from the most notorious racist group in the United States caused the then-presidential candidate to refuse the endorsement.

“I refuse any kind of support coming from supremacist groups. I suggest that, for the sake of coherence, they support the left-wing candidate, who loves to segregate society. To exploit this to influence an election in Brazil is very stupid! It’s not knowing the Brazilian people, who are mixed-race,” said Bolsonaro. He also said that his children do not “run the risk” of dating black people, because they would have been “very well raised”.

Source: El País