RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Doctors and scientists worldwide are looking for superheroes disguised as ordinary people. These are people who, after being infected with the coronavirus, have developed highly effective antibodies to neutralize the pathogen.

Their blood plasma is among the potential treatments to save other patients’ lives. But finding the best antibodies is a task of cosmological proportions.

Each individual holds over one billion B immune cells, each capable of producing a specific, unique type of antibody. When multiplied by the more than four million infected individuals worldwide, the result is four quadrillion possibilities, 2,000 times more than the number of stars in the whole universe.

A few days ago, data from the most extensive research of this kind to date were published. It is a study of 1,343 individuals from New York and surrounding areas with either confirmed or suspected infections. The vast majority were mild cases. The study findings show a reassuring fact: 99 percent of the 624 confirmed cases developed antibodies against the SARS-Cov-2 virus that causes Covid-19.

Although this depends on each individual case and has not yet been proven, these antibodies can be expected to confer a certain degree of immunity. The likelihood of someone becoming infected again becomes slimmer. In fact, the main proponents of this theory, the South Korean health authorities, found that the 260 potential reinfected individuals detected were false positives.

The US study is preliminary and has not been reviewed by independent experts, but its authors, from the Mount Sinai Hospital School of Medicine in New York, are among the most prestigious teams in their field and are involved in the clinical trial to treat covid-19 patients with hyperimmune plasma.

The most promising aspect of the study is that the amount of antibodies produced is not connected to the age, sex, and severity of the disease: all seem to produce these protective proteins. The most severe patients produce more antibodies, as a preliminary study in China showed with 175 patients, so that, theoretically, they would be as protected or more so than the others, argue the study’s authors.

Another significant finding is that people reach their peak of antibody production 15 days after the symptoms have subsided, so waiting a couple of weeks after recovery is recommended for a reliable test, or else there will be false negatives. Perhaps that is why earlier studies show that some people overcame the disease without having produced antibodies, the authors point out.

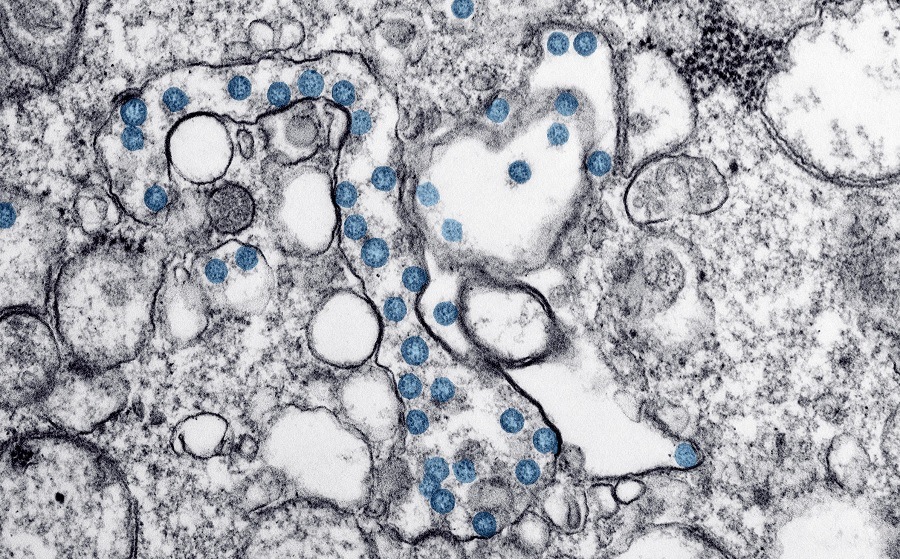

The amount of antibodies in a patient has a correlation with their plasma’s ability to neutralize the virus, as the same team explained in a prior study to demonstrate the value of their test published in Nature Medicine. The antibodies bind to the S protein that the virus uses to penetrate human cells and thus prevent new infections.

However, the paper points out that the amount of antibodies required to ensure immunity is not yet known, nor what their neutralizing capacity is; these need to be proven in future.

“This finally proves something that we believed to be obvious, but which could not be confirmed due to the poor reliability of tests,” explains Carmen Cámara, an immunologist at La Paz Hospital (Madrid) and secretary of the Spanish Society of Immunology.

“The New York study is the most comprehensive screening we’ve seen so far, and it was conducted with a rigorously validated test that is 92 percent accurate. It’s something that was impossible until now, with the commercial tests, because even those claiming to be 80 percent accurate are in fact 40 percent,” she explains.

A study conducted in China with 14 recovered patients has provided another positive finding: most of them not only produce neutralizing antibodies (IgG), but also T lymphocytes capable of destroying the infected cells. “In an infection, it is vital to destroy the weapons factory – the infected cells – and not just the weapons, the viral particles,” explains immunologist Margarida del Val, of CSCI (Spain’s government scientific research agency).

This study “is good news,” she says, adding that “luckily the novel coronavirus can’t evade triggering all the immunological weaponry”.

Now the main question is how long the immunity lasts: months, years? The harsh reality is that it will only be known over time. Until then, one can only make assumptions based on what one knows about other viruses. The human coronaviruses that are genetically most similar to the new SARS-CoV-2 are those causing the SARS and MERS epidemics.

In both cases, neutralizing antibodies were detected in patients up to three years after infection. In the case of the SARS virus, there are still neutralizing antibodies after 13 years. The question is whether they continue to function, which is difficult to answer.

The best way to prove that an antibody is functional is to use it to fight the virus in healthy human cell culture. This can only be performed in high-security (P-3) laboratories. “In hospital settings this kind of trial is unthinkable, we don’t have P-3s and it would be impossible to analyze the antibodies of each patient in a study of this kind,” explains Cámara.

Another option is to employ humanized animals that produce the ACE2 protein, which the coronavirus uses to attack our cells. This is what a group of Chinese scientists has done in a study published in Science magazine this week.

They proved that two antibodies isolated from a patient were successful in reducing the level of virus in the lungs of rats, and one of them prevented injuries to these organs. Another preliminary study shows data from a patient who generated more than 200 different antibodies against the virus, including two capable of neutralizing it by as much as 99 percent.

This shows that the immune response is both powerful and specific for the novel virus, as these same antibodies do not bind to SARS or MERS viruses, whose S protein is slightly different in the area that binds to human cells, known as the receptor-binding domain (RBD).

In Spain, the search for hyperimmune serum is now beginning. To date, it is unclear who the best donors may be. At first, they were believed to be youths with a mild form of the disease, but then it was proven that older, more severe patients developed more antibodies and had greater potential, explains Cristina Avendaño, a pharmacologist at the Puerta de Hierro Hospital on the outskirts of Madrid, who leads a clinical trial with hyperimmune plasma in 30 Spanish hospitals.

“For now we have just over 100 donors and 61 patients, but we still have to determine the effectiveness of the different antibodies,” she says. To this end, José Alcamí, a researcher at the National Center of Microbiology, has designed a way to avoid the need to use a maximum-security laboratory. It involves employing deactivated versions of the AIDS virus, which are unable to generate the disease, to which the S protein of the coronavirus is added in its outer casing.

As if it were a video game, this pseudovirus and the antibodies in each patient’s plasma fight in a kind of dojo (martial arts ring) made up of healthy human cells. The fewer infected cells there are at the end of the fight, the more effective the serum will be.

Therefore, doctors in Spain are looking for the superheroes of the coronavirus, whose blood could save lives. Alcamí hopes to have results by the end of this month.

Source: El País