RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – One of the strangest phone calls ever is the one connecting scientists at Concordia station, in the middle of Antarctica, to astronauts at the International Space Station, 400 kilometers above the Earth’s surface.

This connection shows the great bond that unites these two human groups: the immense isolation in which they live. So much so that this spacecraft is the closest neighbor to the Concordia, since the closest humans on earth are 600 kilometers away at Vostok’s Russian station on Antarctica.

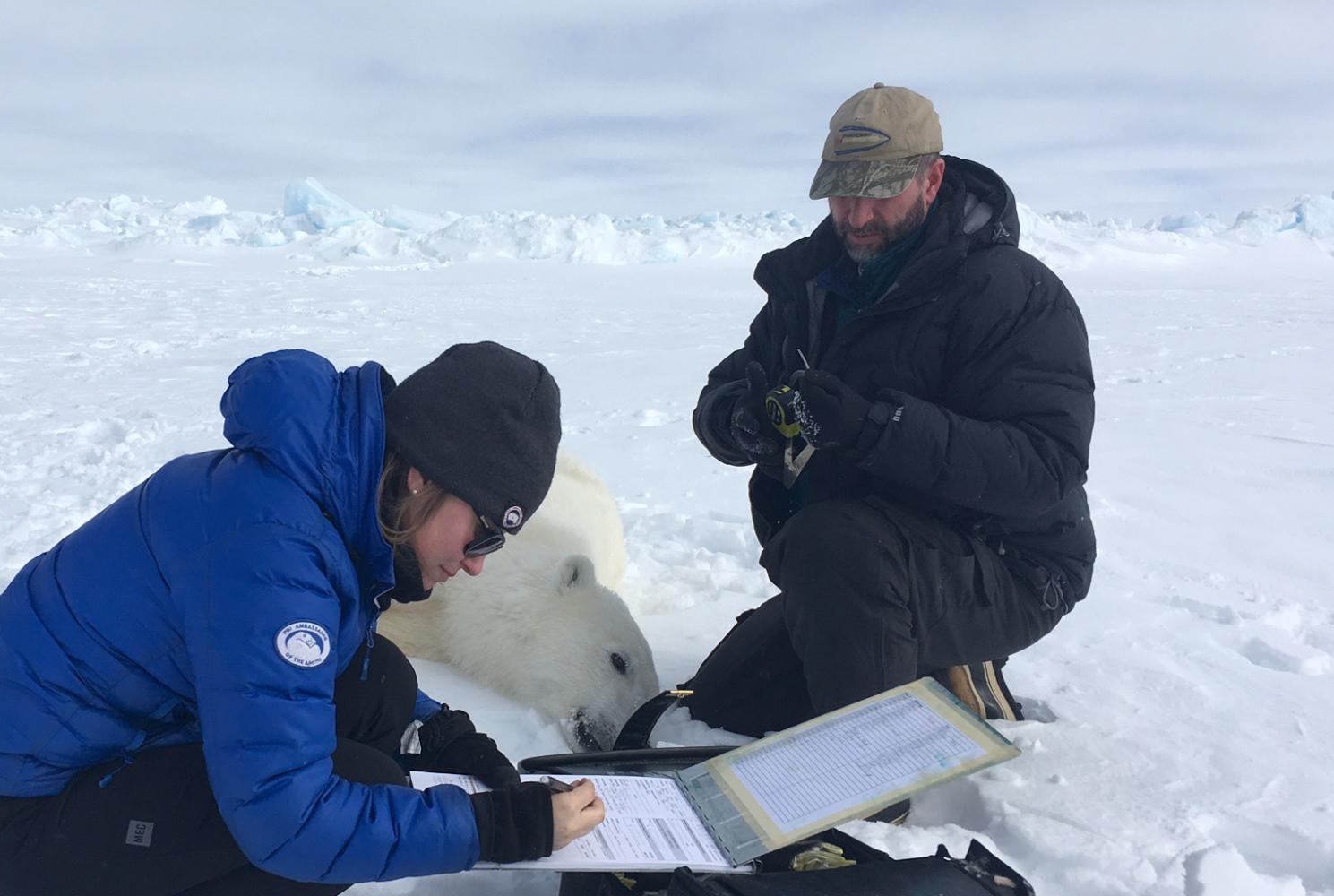

The European Space Agency (ESA) puts astronauts in contact with this station as part of its study of the psychological effects of seclusion. For decades, many experts have been studying the mental health of this small group of people in extreme situations; now their lessons are useful to the entire planet, as there are billions of people locked up in their homes as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“In recent days we have heard many stories of increased feelings of depression, anxiety, irritability and sleep disorders experienced by people isolated due to the coronavirus, very similar to what some astronauts and polar expeditionaries experience,” says Larry Palinkas, psychologist at the University of Southern California.

“Not all humans can adapt easily,” adds this expert, who has been studying people submitted to these conditions for decades, also for NASA. But while it’s not an easy challenge, Palinkas believes that the astronauts and expeditionaries’ experience can be of great use now. Evidently, not neglecting the social and economic conditions of each: the astronauts do not have to repair the ship with a baby in their arms or go down the street to earn some change to pay the rent.

“They know there will be bad days, but they will pass,” says Emma Barrett of the University of Manchester, an expert in psychology of such extreme situations. “The important thing is to focus on the present and try not to dwell on an uncertain future. Focus on the things you can control, not the things you can’t. Anxiety can get out of hand if you spend all day worrying about the future,” Barrett insists.

Many 19th-century polar adventures would end like that of American explorer Arthur Greely, with the group exposed “to mutiny, madness, suicide and cannibalism, with only six survivors out of a crew of 25 men,” as Palinkas recounts. But the current conditions of the Concordia scientists are not as extreme, with all their basic needs covered, so they resemble much more what today’s quarantined population is living in their homes.

A review of the polar scientists’ typical symptoms may sound very familiar: headaches, boredom, fatigue, lack of attention to personal hygiene, less motivation with “intellectual inertia” and weight gain caused by an increased appetite. “However,” Palinkas warns in one of his papers, “the most common symptoms of people on polar expeditions include sleep disorders, deteriorating cognitive performance, negative emotions, and interpersonal tension and conflict”.

And, among all of them, a more diffuse symptom stands out, but one that many cloistered people are already suffering: mental dullness. “Some people may experience difficulty remembering things and completing certain tasks as their minds begin to experience a form of psychological hibernation,” explains Palinkas.

This brain hibernation is a phenomenon that has been observed during long-term polar-based spatial simulation experiments and refers to a “deceleration of the body and mind due to restricted stimulation,” in Palinkas’ words.

“People will sleep longer or have trouble sleeping, and their cognitive functioning will display signs of slight deterioration,” he adds. A recent study at Concordia found that brains were getting carried away rather than facing the situation.

“It’s a protection mechanism against chronic stress, which makes sense: if conditions are uncontrollable, but you know that at some point in the future things will improve, you can choose to reduce mental efforts to preserve energy,” explained Nathan Smith of the University of Manchester.

Astronauts and expeditionaries are selected for these hard trials according to their psychological profile, and they undergo specific training, such as when ESA holds their elected representatives for days in caves in Sardinia (Italy). None of this is valid in the current situation: everyone is in this prison and nobody has had time to prepare.

But experience can offer some useful keys to the population. For one, as many experts have said, adapt to change by establishing a routine that helps reduce uncertainty, by building a firm structure in everyday life.

Also exercise.

Between 2010 and 2011, eight volunteers spent 520 days on a simulated mission to Mars. The hundreds of studies conducted on the crew’s behavior in the Mars 500 mission show that endurance exercise (running, pedaling) not only helped physically but also improved adaptation in terms of psychological and cognitive performance, while strength exercises would not provide this benefit.

Experts also recommend writing a diary, for instance, as it provides an escape route to expressing your feelings, in addition to taking up time.

Diego Urbina, one of the Mars 500 crew members, recommended writing letters or e-mails a few days, rather than posting on social media: “Writing long messages and letters helps reflection, introspection and allows deeper human contact than we can have today through WhatsApp”. Barrett also believes it is useful because it helps make sense of chaos.

In addition, Urbina advises finding a space of your own to isolate yourself from other fellow confinees. It is something that emerges in all studies: no matter how small the ship or the station, everyone should have a sacred place where they can feel comfortable and that others respect.

“Today was difficult. We don’t understand what’s happening to us. We walk in silence next to each other, feeling offended. We need to find some way to make things better.” These words were written by Soviet cosmonaut Valentine Lebedev, who spent 211 days aboard the Mir in 1982: he estimated that 30 percent of time in space involved crew conflicts.

The conflicts were usually due to simple misunderstandings that were amplified by confinement. Dr. Beth Healey, who spent a year at the Concordia station for the ESA studies, summed it up as follows: “Everyone notices everything. Even a change in what you had for breakfast becomes the subject of long squabbles”.

That’s why respecting each other’s space and being particularly tolerant and engaging in dialogue if you have to spend confinement with others. “Focus on being pleasant,” Barrett sums up.

To reduce friction, at the polar station they force everyone to eat together to overcome the temptation to avoid someone permanently. And both astronauts and scientists use a resource in our grasp: to celebrate. Celebrating birthdays, small achievements or devising reasons for organizing a party is crucial to enjoying a moment of fun relaxation.

“These people value the positive aspects of their situation, like a perfect cup of coffee or a few laughs, they focus on small achievements and celebrate those small victories with the group,” Barrett points out.

“Some people may experience difficulties remembering things and completing certain tasks as their minds begin to experience a form of psychological hibernation”.

Faced with boredom, this expert reminds us that they usually fight monotony with passive activities, such as watching television, and active activities, such as creating mini theatrical presentations, sharing a moment of play, cooking, etc. “What has surprised me these days is the creativity of people to stay mentally healthy, happy and connected with others,” says Palinkas. Whether it’s evening celebrations on the balcony or walking the dog around the neighborhood, these social contacts, “however brief, are extremely important and help you feel that you’re not the only one going through these changes,” he says.

Last but not least, we have a great tool: humor. “Laughter is the best medicine,” Palinkas says, “it’s certainly important because it allows the exercise of creativity and helps deflect social tension and reduce potential conflict”.

A study with several space crews observed that humor was a common tool to address tensions in all cultures and situations, and although they used all kinds of humor, they tended to use the positive more. By using it, levels of loneliness, depression, stress, tension, and anxiety fell among astronauts, while they improved feelings of friendship, self-esteem, and optimism.

In a study of Israeli submarine crews, scientists were surprised at the high levels of cynicism and humor with which sailors faced confinement. The main display of this attitude was the Night’s Diary, a kind of satirical newspaper that they produced with photos, links to news and other materials, to revisit what had happened during the day.

“It’s our way of dealing with painful things and expressing cynicism. It reflects cynicism. Instead of someone telling others what they want to tell them, they simply add it to the Night’s Diary and that’s how everyone knows. It’s a fun and cynical newspaper that makes the routine easier, to cause laughter,” explained one of the crew.

“There’s plenty of evidence that the right kind of humor can be crucial in coping with high levels of stress when faced with adversity. But one must be careful: One person’s cheerful joke can be upsetting to another or they may even feel criticized. Humor helps relieve stress as long as it doesn’t become intimidating,” Barrett says.

Source: El País