RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – At its peak, every crisis seems bound to change the world. The 2008 Great Recession should have been the rebuilding of capitalism. That of sovereign debt in southern Europe, which would have laid the foundations for a new European Union with greater solidarity.

And this, the coronavirus, “will create a new world with other rules,” as European Internal Market Minister Thierry Breton pointed out last week. Most likely, as on the two previous occasions, this axiom will end up being blown away by the wind, and the change of course will have been nothing more than well-intentioned words.

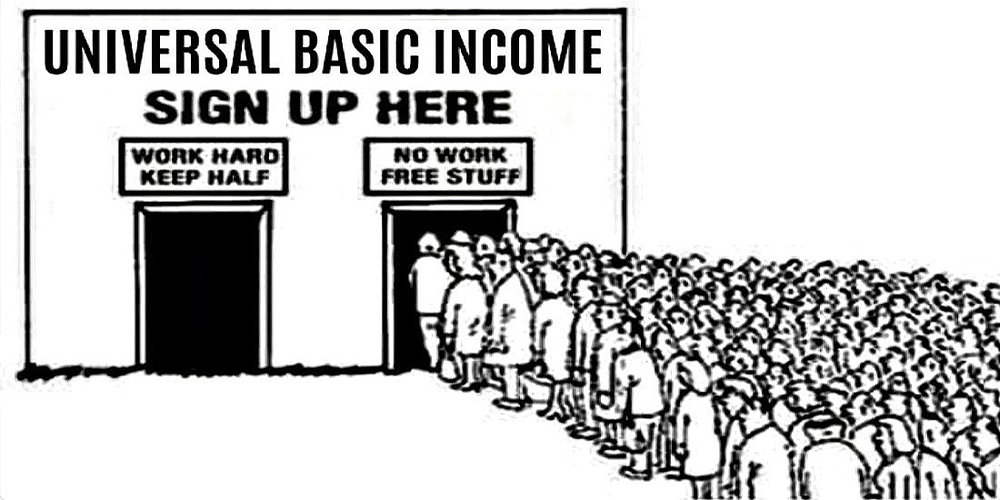

However, far from the pompous speeches and away from the spotlight, some ideas hitherto regarded as niche ideas are starting to take root: basic income (universal or not), a kind of guarantee of income to the citizen for the simple fact of being so, has gained more followers in the last few days than in all preceding years, taking an exponential leap in public debate and presenting a solid proposition in the menu of potential solutions to escape the economic and social quagmire of the pandemic.

And even more importantly, it is something that is beginning to take hold in the field of facts, with different governments embracing their own versions of this tool to fight a recession that is already, in the words of IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva, “as bad or worse than 2009”.

The United States, a country where the debate on basic income was limited to relatively watertight academic fields and minority electoral proposals, like that of former Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang, took a first and decisive step in this direction: it will grant its citizens US$1,200 (R$6,420) in one go, an amount that is gradually reduced for those who earn more than US$75,000 a year and that leaves out only those who earn US$99,000 or more.

The goal, according to the White House, is to mitigate the reduction in income and ensure the essentials. “The fundamentals are identical [to what I propose]: it is a direct transfer to individuals and homes,” Yang told NPR public radio. “The major difference is that I suggest it be forever, as a basic right of citizenship to cover basic needs, and the incentive package is designed to last only a few months”.

In parallel, the Brazilian Congress has just passed a payment scheme – in this case, much more distant from universality – of R$600 during a quarter to 60 million casual workers.

And Spain is preparing to launch a minimum income in the next few days that will apparently be around €440 euros (R$2,540) per month, in line with the aid approved last week for temporary workers who are out of work as a result of the economic slowdown caused by the epidemic and what was proposed by AIREF (the Spanish fiscal authority) in mid-2009.

The goal will again be to protect the most vulnerable groups. In other European countries, like the United Kingdom, the “universal emergency income” has also made its way into Parliament forcefully, but it has not yet persuaded the conservative and unorthodox Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

Why a basic income, and why now? Its growing number of advocates see it as a useful tool to contain the social emergency that has led millions of people to find themselves with no income at all overnight. And, they add, it would also be a positive measure to reactivate demand when quarantines can be lifted.

So far, in Europe, the contingency has been handled with collective aid and, as in Italy, even with food vouchers in an attempt to lower the growing social tension in the south of the country.

But in Latin America and the remainder of the emerging bloc, where informality reaches far higher levels than in developed countries, crisis management is being and will be much more cumbersome.

“In these countries, which are still in an initial stage of the pandemic, basic income should be implemented as soon as possible: you can’t buy soap or have clean water without the money to do so, and it’s simpler to transfer it directly to people than to organize a complex scheme of subsidies,” points out Guy Standing, a professor at the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London and author of the book Basic Income: And How We Can Make It Happen.

All schemes designed or implemented since the beginning of the pandemic are, however, designed to be phased out as soon as things calm down, as Philippe van Parijs, professor at the Catholic University of Louvain (Belgium), points out.

“They have a useful purpose and may be the best tool available, but they are intrinsically temporary,” stresses the one who is perhaps the greatest global ambassador of the concept.

“Many who criticized it now advocate it”

Basic income has not ceased to become popular in recent years, following the rise in inequality and the reduction of the welfare state. But it is far from being a new concept: it began to sound, albeit in very small circles, in the 18th century, and in its journey it succeeded in gathering around it economists of such different ideological directions as John Kenneth Galbraith, Milton Friedman and James Meade, among others.

And it captured thinkers two centuries apart like Thomas Paine (1737-1809) and Bertrand Russell (1872-1970). However, it has never come this close to becoming a reality as it does today. “I believe in opportunistic utopia. Crises can generate opportunities for great advancements and we must seize the momentum,” encourages Van Parijs, co-author of Basic Income: A Radical Proposal for a Free Society and a Sane Economy.

The universal aspect of basic income -the most interesting, but also the most complex because of the associated costs- is attracting greater interest at a time of economic uncertainty, as Louise Haagh of the Political Science Department at York University (United Kingdom) acknowledges.

“The failure of our system both to specifically address this crisis and, more generally, to provide real economic security is becoming apparent,” she notes via email. “It’s just one piece of the puzzle, but at least it would be a real attempt at acknowledging everyone’s rights and economic status”. Guy Standing also descries a change of pattern: “Many politicians, economists and media, who in the past were hostile to the idea, now advocate it”.

The cost of a permanent basic income, rather than just an emergency one, varies greatly from country to country. The minimum income proposed in Spain by José Luis Escrivá, today’s minister of social welfare, when he was in charge of AIREF, would cost €3.5 billion euros (R$18.7 billion) if the overlapping with other social programs were discounted and would reduce poverty by 46 to 60 percent. A more ambitious solution, such as a genuinely universal and permanent basic income of just €620 per month per resident, would represent a burden of almost €190 billion per year, approximately 18 percent of GDP, as estimated in 2017 by BBVA’s study service.

To adopt it, both in European and emerging countries, it is necessary to start “a frontal fight against tax evasion and competition [between territories] and rethink the goal of austerity,” Haagh, president of the Global Network of Basic Income (BEM), says.

In Latin America, a region plagued by inequality and poverty, and where its meaning is multiplied, handing over to all households enough to cross the poverty line would have a cost to the treasury equivalent to 4.7 percent of GDP, according to a recent study by ECLAC, the UN branch for the economic development of the subcontinent.

“It wouldn’t cost that much and it would provide economic security at a time of enormous uncertainty,” stresses Alicia Bárcena, the agency’s executive secretary. “This crisis invites us to rethink the economy, globalization and capitalism. Innovative solutions are required, and basic income is one of them”.

Utopia is closer than ever to becoming reality.