RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – What could make an industrial entrepreneur for over 40 years start raising pigs? “All I care about is their shit,” replies Romário Schaefer, owner of Stein ceramics in Paraná, laughing.

The pig’s waste from his property in the municipality of Entre Rios do Oeste (PR), 133 kilometers from Foz do Iguaçu, is raw material for the production of biogas. The fuel supplies a generator that has reduced the company’s electricity costs by half.

Previously an environmental problem, the waste from agricultural production has become a source of income for producers in western Paraná and, among the most enthusiastic, it is already called the “rural pre-salt” in a reference to Brazil’s offshore deep water oil reserves.

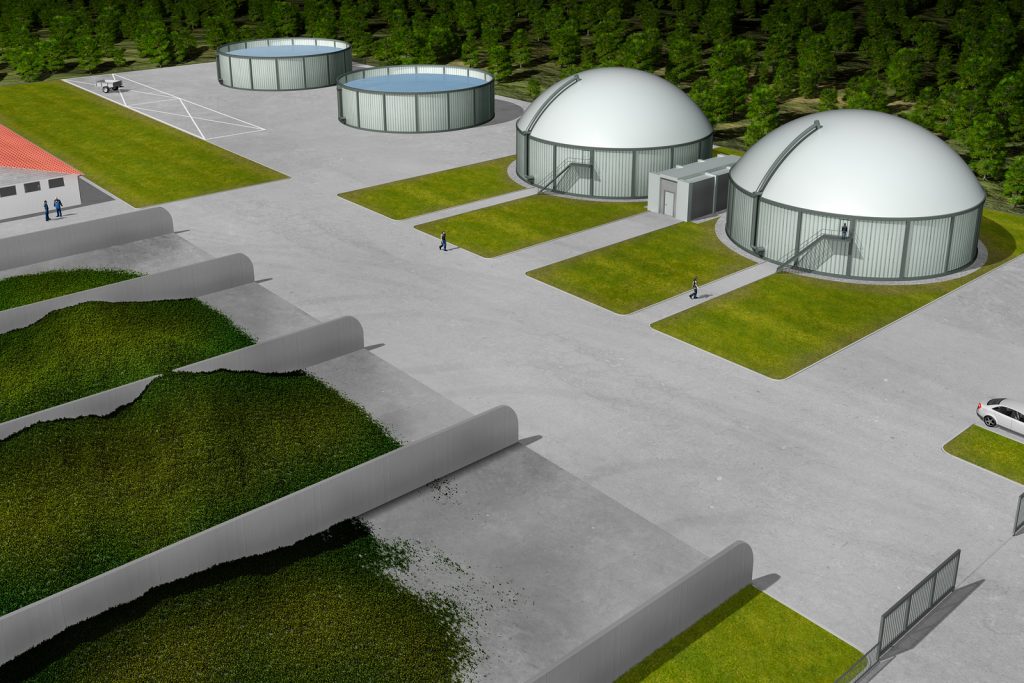

To generate the fuel, a biodigester needs to be installed, a structure that allows the processing of manure. With a relatively high initial investment of R$75,000 to R$100,000, the venture has become viable through the framework of distributed generation (DRG), in which consumers start to generate their own energy.

The method, which has subsidies paid by all Brazilians on the electricity bill, is best known for solar panels, but extends far beyond it and includes energy generated by wind power, sugarcane bagasse, landfills and also animal manure.

Those traveling through western Paraná are usually limited to visiting the famous Iguaçu Falls. Those staying longer can also visit Paraguay for shopping, and the Itaipu dam, the second largest hydroelectric plant in the world. But on the way to these destinations, tourists will soon realize that what really drives the region is agribusiness.

Manure

Paraná is the largest swine producer in the country. In terms of poultry, it only loses out to Santa Catarina. And it was 12 years ago, during inspections at the 1,350 square kilometer Itaipu reservoir, that experts noticed the accumulation of animal protein, which comes from the waste of the region’s agricultural production.

The west part of the state concentrates 4.2 million pigs, 105 million poultry and 1.3 million cattle. To get an idea, the estimate is that their annual waste generation is equivalent to the water that flows down Iguaçu Falls in five minutes.

Extending the useful life of the Itaipu plant to the maximum – today estimated at 182 years – requires actions that avoid silting up its reservoir. To do so, finding a sustainable way to handle this waste was crucial. Due to this need, Itaipu, through the hydroelectric power plant’s Technology Park, signed a partnership with the International Center for Renewable Energy (CIBiogás).

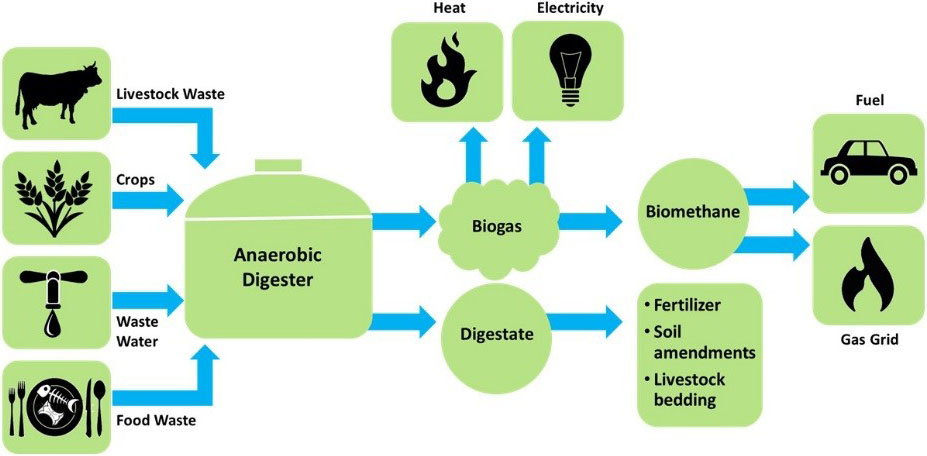

CIBiogás’ studies showed that a property with 800 pigs can generate enough light to supply 23 homes. To do so, waste must be processed and the biogas separated. According to experts, it is a gaseous compound resulting from the anaerobic degradation of organic matter by microorganisms. The process also generates digestate, a natural fertilizer.

According to Rafael González, CIBiogás’ director-president, the agro-industry in the southern region of the country has the potential to produce 3 billion cubic meters of biogas per year, enough to supply 2.5 million low-income homes.

Electricity bill

Schaefer, from Stein Ceramics, had no experience in agribusiness. It was the potential to save energy that encouraged the industrialist to invest in pig farming.

The family has owned Stein ceramics for 40 years and produces 40,000 bricks per day, with monthly sales of R$500,000. In 2012, Schaefer bought a 24-hour rotary kiln that cannot be turned off. Spending on electricity has increased considerably. “That’s when we found the biogas alternative,” he says.

In 2013, he invested R$300,000 in building the farm and buying a biodigester and his own generator. He started with 3,000 pigs. The biogas generated – 446 cubic meters per day – yields 28 megawatt-hours per month, energy fully used in the industry.

“Religiously,” as he describes it, the generator is turned on between 6 PM and 9 PM, peak time, when the local distributor can charge five times more for the energy.

Most recently, the manufacturer automated ceramic processing and decided to double the herd to 7,000 pigs. Now, the biogas will also be burned directly in its own furnaces.

“It was fantastic. I have reduced my production cost by lowering the electricity bill, and at the same time I am raising pigs, which yields income that pays for my investment,” says the producer.

The return on investment came in three years. Schaefer managed to reduce his electricity bill by half, to about R$30,000 a month. The manufacturer donates the biofertilizer generated to his neighbors.

Farm was a pioneer in generation

Partner and owner of São Pedro Farm, Pedro Colombari was the first producer to invest in distributed generation in the country in 2008. On his property, located in São Miguel do Iguaçu, he raises 5,000 pigs and 400 cattle, and also plants corn and soybeans. With biogas, he saves between R$5,000 and R$7,000 a month in electric energy at the farm and other properties and family properties.

The property was the pioneer of a pilot project in partnership with Itaipu. The farm generates 770 cubic meters of biogas per day and produces 32 megawatt-hours per month. The energy generated on the farm costs one third of the amount charged by the distributor.

The biofertilizer is used in the planting of pastures. With increased energy security, he purchased more electric machines for the property – an irrigation pump and ventilators for the farm.

Biogas potential equals double the gas coming from Bolivia

Brazil’s biogas potential, considering all its sources, represents up to twice the average volume of natural gas imported from Bolivia in 2018. The data is part of the National Electric Energy Plan (PDE) 2029, released on February 11th. The aim is to use the fuel to replace diesel, in addition to adding the input to the fossil natural gas in the gas pipeline network.

If in Brazil this technology is starting to increase its presence in the energy grid, in Europe there are already 17,500 plants producing energy through biogas.

Germany leads the ranking, with almost 10,000 ventures. The progress came amid the conflicts between Russia and the Ukraine over gas, which in 2009 cut off supplies to the country – until then, 40 percent of the gas supplying the Germans had come by this route.

City has collective biogas project

For small farms, power generation by biogas is not always feasible. But through a collective solution, the Entre Rios do Oeste City Hall was able to set up a project that generated savings and solved an environmental liability.

With a population of 4,600 people and 255,000 pigs, the municipality had a high pollution burden. To address the issue, the city built a 22-kilometer collecting network to collect the biogas generated by 18 properties — each paid its own biodigester. Some 40,000 pigs produce 4,700 cubic meters of biogas per day, which are then taken to a small-scale thermoelectric plant.

The plant’s power generation cuts the electricity bill of 62 public buildings. In return, producers are paid R$0.28 per cubic meter of biogas produced. Each one earns between R$800 and R$5,000.

Despite the payment, the city hall saves between 5 and 15 percent in relation to what it spent on energy before the project, says the municipal secretary of Basic Sanitation, Renewable Energy and Public Lighting, Carlos Eduardo Levandowski.

Quality of Life

One of the producers in the network is Claudinei Jardel Stein, from Santo Expedito Farm. He raises 7,400 pigs and earns an average of R$1,500 from the municipality. His monthly electricity bill varies between R$1,200 and R$1,400. The biodigester has changed the property’s quality of life. “The stench and the flies have decreased greatly,” he says.

Ademir Escher, who is also part of the project, agrees. He lives on the farm with his family and says that after the biodigester, his daughter stopped complaining about the bad smell in her clothes. He earns between R$1,000 and R$1,200 a month from the city for the biogas generated by 1,200 pigs.

The project, structured by CIBiogás, cost R$17.5 million raised with research and development (R&D) funds, in a partnership between Itaipu, Itaipu Technology Park and the distributor Copel.