RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – “As if personal travails were not enough, it became difficult for me to devote myself to literary daydreams without being affected by recent events in our country”. The sentence on the front page of “Essa Gente” (“Those People”) is in a letter from the main character, writer Manuel Duarte, but it sounds like a confession by the author himself, Chico Buarque.

He goes on to apologize for disturbing his publisher “at a time when the economic crisis does not seem to have cooled down as expected” and regrets the conditions of the publishing market. He concludes by promising a novel that will bring great joys – which is not often the case, bearing in mind the customary anguish of Chico’s literature.

While his novels usually take place in undefined times or in a more distant past, this Chico Buarque has both his feet firmly planted in 2019.

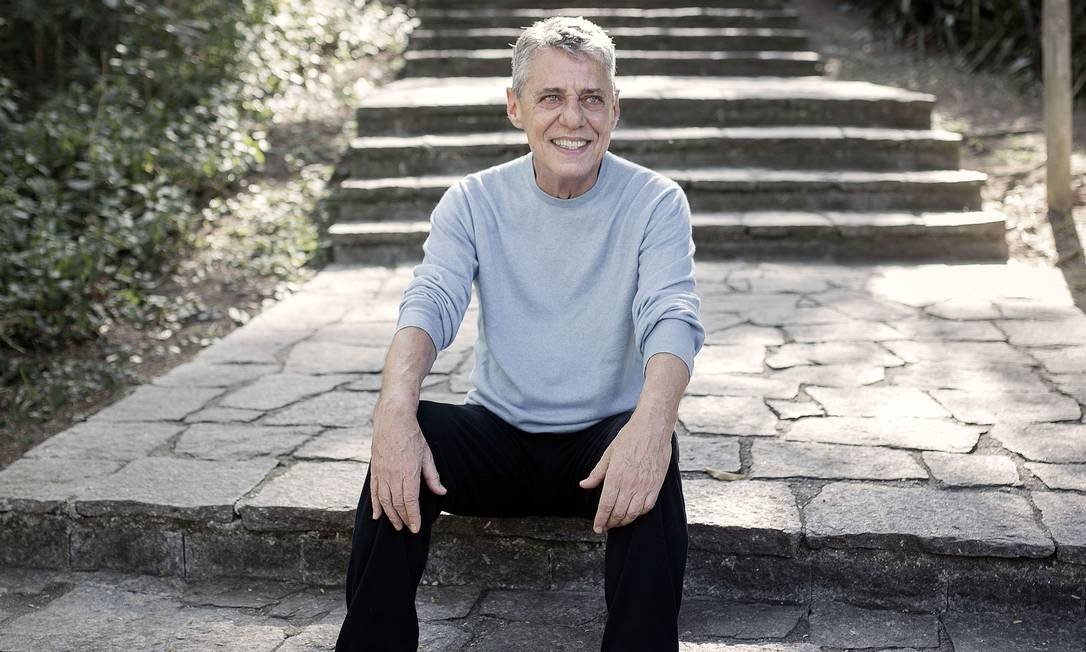

It is the first book that the 75-year-old author has written after receiving the Camões Award in May, the highest distinction for a Portuguese-speaking author, as well as the first to be published under the government of Jair Bolsonaro.

This is intertwined with the President’s implicit refusal to sign the official award, which Chico promptly taunted in his Instagram account – “Bolsonaro’s failure to sign the diploma is to me a second Camões award”.

While virtually every artist talks about almost everything all the time, Chico nurtures an unusual public silence. He gives no interviews, keeps a private monastic life – with the exception of appearances at rallies in favor of the PT candidacy last year, against Lula’s imprisonment and the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff.

But it still seems insufficient, given the thirst with which his fan base awaits each new album and each new book – it has been five years since “O Irmão Alemão” (“My German Brother”) -, a voracious yearning for the words of a rare figure who reconciles popularity with intellectual stature.

“Essa Gente” must please such people. Duarte’s torments, although not eminently political, do not fail to mirror those who have plagued the left-wing since the last elections.

Written in the form of a diary, the book includes, for instance, in an entry marked in January 2019, the central character’s cold realization that he could now, by decree, have four firearms in his house. Written since October last year, when the artist wrapped up his tour of the album “Caravanas” and the right-wing trampled the ballot box, the book captured the spirit of a time when political violence was flourishing.

“You have to strike out, you have to kill, the ranting thickens/ Anger, daughter of fear, is the mother of cowardice.” These are verses from “As Caravanas”, from the 2017 album, that echo in tune with the book’s plot, with a scene in which the main character watches, indifferent, as a friend from the Country Club flails at an old Indian who was lying on the sidewalk.

There are selfies with police officers who shot a burglar dead, there’s a snobby neighbor who happens to be a federal judge, there’s an ironic mention of wearing a Brazilian national team jersey at a school meeting (after Duarte’s firstborn was mocked as the ” son of communists”), the news that soldiers shot 80 rounds at a black musician’s car.

The references to the president are not nominal, but direct. One of the protagonist’s ex-wives, smitten by an agribusiness baron, has a life-size statue of a man, all in gold, which she dresses with a green-yellow sash.

The political events in Brazil were not the primary plan for Chico’s writing but ended up being used as a resource to develop fiction.

The novel’s plot, which runs until September 29th, depicts the author with prior literary success, struggling to deliver a new novel, having two ex-wives for whom emotional ties still remain, plus desire for a young Dutch woman, Rebekka, who is married to a lifeguard from Vidigal hill.

(The protagonist knows this lifeguard after being rescued from drowning in the sea, an event that evokes a real, if little-known, event of Chico’s own youth.)

The decision to incorporate newspaper news into the novel allows Chico to place Rebekka in a demonstration that in fact took place in Rio de Janeiro on the date annotated in the diary. And the celebration of a goal by Flamengo on a day when, in fact, the team scored.

The fragmentation of the work also produces a mix of voices, including passages in which the narrative is purportedly made by other characters – and, thus, Chico uses material from novel ideas that have not progressed further.

Letters from translator Maria Clara (one of Duarte’s ex-wives) to an English-speaking author date back to the end of 2017, when Chico wrote them thinking of a plot that revolved around them.

The same goes for passages dated December 2016 about a castrated black singer, who in the plot of “Essa Gente” ends up fulfilling an important, but lateral function – he became a character in the bestseller written by the protagonist, “O Eunuco do Paço Real” (The Imperial Eunuch).

The complexity of this patchwork serves to confuse an already typical authorial muddle of Chico Buarque’s literary work. But it is unmistakable that this is an author who, sprinkling his book with so many lynchings, controlled substances, helicopters firing into favelas and even a “growing monarchical sentiment”, is still waiting for “the banner of bedlam to pass us by; it will pass,” as he wrote in his 1985 song “Vai Passar”.

Source: Folhapress