In 2013, Montevideo, Uruguay, hosted a blind wine-tasting contest. Tasters sampled Tannat wines made with a grape originating (but not universally beloved) in France, now a prized Uruguay export. The surprise winner: a Bolivian wine.

It was Bolivia’s first-ever grand gold medal.

To hear Ramon Escobar, the Bolivian American co-founder of Chufly Imports, known for Bolivian wine and spirits, tell it was unbelievable to the judges.

“It was such a shocker,” Escobar says, “that they would not award the medal to the Bolivian winery until they went [there] themselves and verified it was made in Bolivia.”

But when all was said and done, the wine—a 2012 Juan Cruz from Bolivia’s Aranjuez vineyard—received its commendation.

That moment, he believes, was when Bolivian wine started to receive the recognition it deserves, at home and abroad.

The accolades and international attention have snowballed since.

“There’s a growing appreciation in Bolivia for Bolivian wine and the fact that it is high quality and that [Bolivians] should take pride in it,” says Escobar.

“Like many developing countries, it’s a sad reality that people do not associate quality with their domestic stuff—they aspire to import European or foreign brands—and I think that’s slowly starting to turn a corner in Bolivia [with wine].”

Singani, the country’s national spirit, continues to be much more widely consumed, exported, and integrated into daily life. However, seeing locally-made wines on tables outside the country’s wine regions is a shift Escobar has noticed.

You’ll find an entirely local wine list at Gustu, La Paz’s must-visit restaurant from Noma co-founder Claus Meyer (part of its mission to serve only nationally-produced items).

Before the pandemic, Chufly imported Bolivian wines for nine Michelin-starred restaurants in the United States.

Getting the word out is no small feat, coming from a continent already known for some of the world’s best wines.

Argentina and Chile have long been recognized for their Malbecs and Carmeneres, respectively, with Uruguay sneaking up recently as an under-the-radar alternative to both for Tannat.

But before the pandemic, more and more wine lovers were paying attention to Bolivia as a wine destination producing wines that taste like no others nearby.

Altitude is a differentiator for Bolivian wine and why it stands out, explains Escobar.

The average vineyard in Napa is around 1000 feet above sea level; in Burgundy, France, the [average] vineyard would be about two or 300 feet above sea level; in Bolivia, the average vineyard starts at 5200 feet above sea level.

So you’re talking about a different climate where the sun shines a lot stronger, the atmosphere is thinner, and when you take all that into account, the grape changes.

In essence, grapes you think you know taste different when grown in Bolivia.

Tannat is Bolivia’s best-known varietal.

The high-altitude version is better balanced than the sometimes overtly robust lower-altitude ones; Muscat of Alexandria, also used to produce singani, is elsewhere quite sweet.

But those flavors balance out in the highlands and jungle of Bolivia for wines that drink smoothly—with great settings worth traveling for, free of the crowds that fill better-known wine regions (in non-pandemic times, that is).

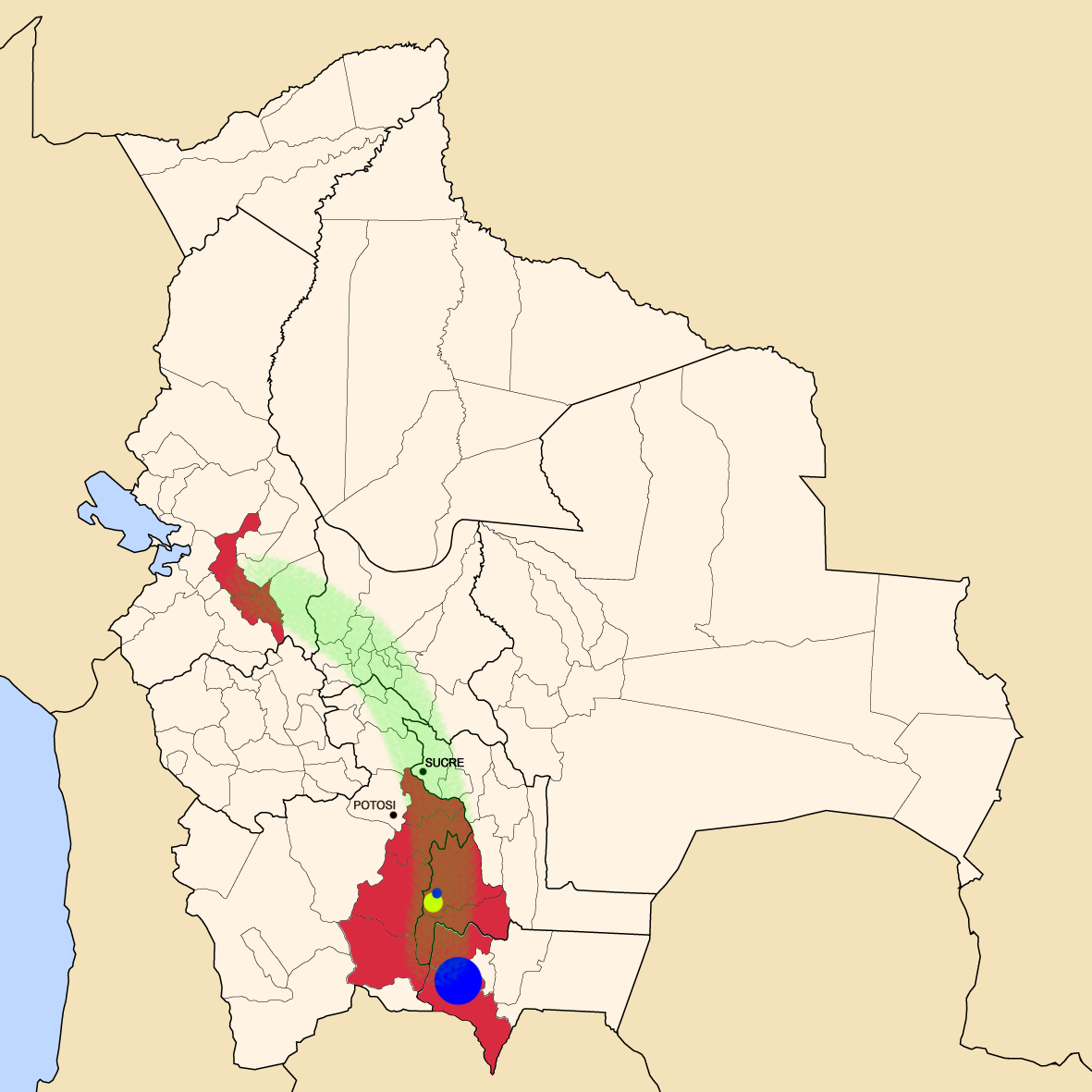

“The three [Bolivian] wine regions are very distinct,” says Escobar.

He describes the Valley of Cinti as “like having a vineyard in the Grand Canyon,” with estates dotting the river that weaves through it.

In Tarija, the country’s central wine-producing region in the south with the bulk of vineyards, a collection of valleys within the larger area are known for a drier climate and resulting Mediterranean style of wine.

Then, in the bohemian village of Samaipata, in the valley of Santa Cruz, travelers can find “the last spot you can grow grapes before you head into the Amazon,” he says.

“It’s just stunning because you can pick grapes, drink wine on a vineyard, and then a 20-minute drive later, you’re in a tropical rainforest, at a waterfall. You can’t do that in winemaking country anywhere else.”

Chufly worked with El Camino Travel (who operates Conde Nast Traveler’s Women Who Travel trips) to make a trip to Bolivia with stops in wine country. Still, the companies had to cancel the journey last year due to the pandemic.

Chufly’s efforts to promote Bolivian wine haven’t stopped, though.

Last month, the company began selling its imported Bolivian wines to consumers online, shipping throughout the U.S. Travelers who might be hoping to visit the country’s vineyards can, for now, sample a range of wines from the vineyards they work with.

On that list:

- Tenants and Cabernet Francs from Aranjuez, the winery that won that first gold medal;

- Muscat of Alexandria and Sangiovese, from female-owned and -run winery Magnus, in Tarija;

- Plus, bottles of Syrah and Spanish Pedro Jimenez from 1750, a winery in the Amazon basin that produces less than 2,000 cases of wine a year (talk about boutique). Retailing for an average of $20-25, they’re also strikingly affordable.

Though Bolivia’s wine industry is much smaller than its neighbors—its wine regions total just one to two percent of Argentina’s—Escobar says the growing interest in Bolivian wine is culturally and economically significant.

Ultimately, Escobar and his co-founder Tealye Long got into this business.

They believe getting the world interested in Bolivia’s great wines has the potential to transform the lives of the Bolivians they work with—which feels especially helpful at a time when tourism dollars have disappeared, and alcohol sales are surging in the U.S.

“If one in four adult Americans drinks a glass of Bolivian wine a year, we will lift 3000 people out of poverty in Bolivia,” says Escobar, referring to analyses his team has conducted.

“If just two of every 1000 bottles of wine that were imported in the United States was from Bolivia, it would lift 1000 people out of poverty.”

This isn’t charity, he adds. “These are beautiful wines crafted by incredible people working to bring a centuries-old tradition into the 21st century.”