By Jorge de Souza

On October 24, 1930, an armed political movement that went down in Brazilian history as the “Revolution of 30” ended an old form of government in which only Paulistas (from São Paulo state) and Mineros (from Minas Gerais state) alternated at the head of the country, the so-called “Republic of Café com Leite.”

The movement also deposed President Washington Luís, prevented his successor Júlio Prestes from taking office, and handed the nation’s leadership to Getúlio Vargas days later.

It was, in short, a coup d’état.

And a very turbulent day in the country’s capital at the time, Rio de Janeiro.

For this reason, on that day, for security reasons, ships were forbidden to enter or leave the port of Rio de Janeiro.

IGNORED THE ORDER

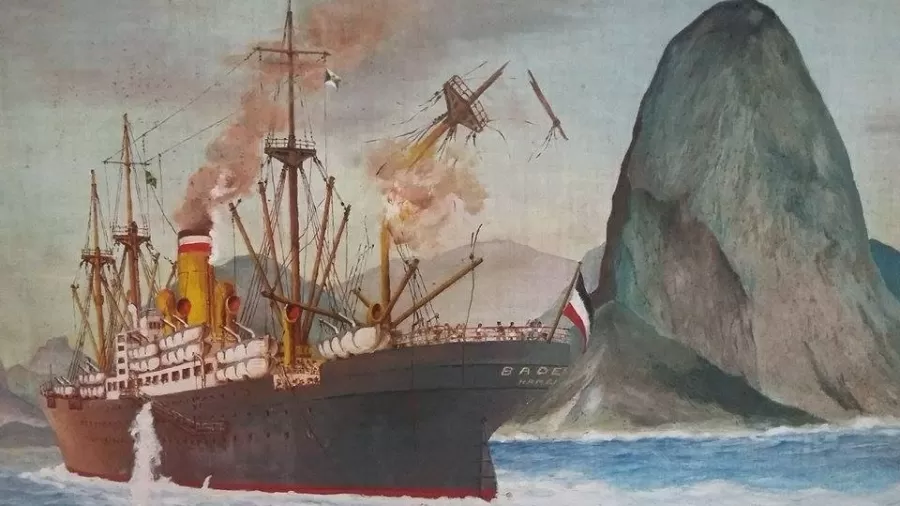

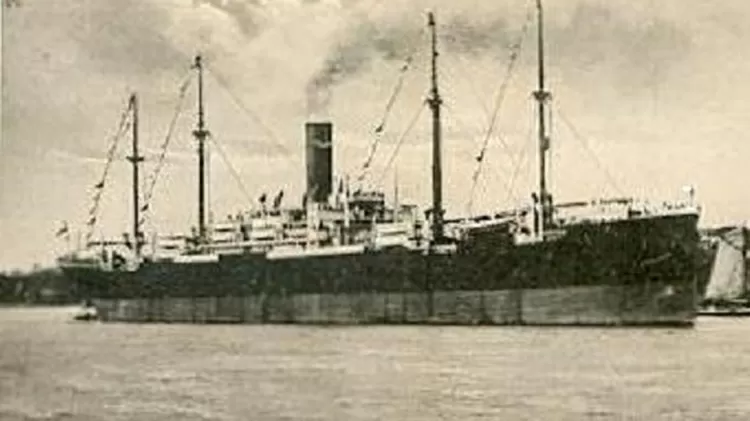

Unaware of the unrest in the streets of the Brazilian capital at the time, the captain of the German passenger ship Baden, which was stuck in the port of Rio de Janeiro during a stopover on its regular route between Hamburg and Buenos Aires, decided to cast off his lines and continue his journey so as not to delay his arrival in Argentina.

But he did not get far.

As it passed Fortaleza de Santa Cruz, one of the fortifications built in the past by the Portuguese to protect Guanabara Bay, the German ship received three harmless warning shots fired with blanks and into the air, as well as a visual sign with flags saying (in Portuguese) not to leave the city and to return to port.

However, the German captain of the ship ignored the warnings and continued sailing.

In the face of this disobedience, the man in charge of the nearest fort, Forte da Vigia, was ordered to stop the ship at any cost – even by firing real ammunition if necessary.

This is precisely what he did.

22 PASSENGERS DIED

One of the shells exploded directly above the aft deck of the Baden, causing extensive damage to the ship, the deaths of 22 passengers, and injuries to 55 others, all foreigners.

Only then did the commander of the German ship turn around and return to the port of Rio de Janeiro, where he was taken away for questioning amid the tumult that the coup had caused in the city.

Did he have fugitives with him?

One of the suspicions that triggered the order to arrest the ship – even at the cost of human lives – was that it was being used to flee coup plotters, which later turned out to be false.

TURMOIL IN RIO DE JANEIRO

Despite the tense situation in the days following the coup, the deliberate attack on a foreign passenger ship in Guanabara Bay, which resulted in the deaths of many innocent people, caused great commotion in the city.

Especially since the victims were modest Spanish and Polish immigrants who were trying to start a new life in Argentina after the economic crisis triggered by the end of World War I years earlier.

The removal of the bodies from the ship so moved the Cariocas that the most important newspaper at the time, Correio da Manhã, decided to launch a fundraising campaign for the wounded and relatives of the victims.

It was a mobilization rarely seen before in the federal capital.

OUTRAGE IN EUROPE

On the other side of the Atlantic, news of the deliberate bombing of a passenger ship manned by guest workers caused outrage both in Germany, the ship’s owner and in Spain, where most of the occupants came from.

Both countries immediately called on the then-confused Brazilian government to conduct a thorough investigation to punish those responsible.

AN UNPRECEDENTED CASE

But Brazil, embroiled in its own political problems at the time, had no way of doing so to their satisfaction.

Apart from the fact that it was an unprecedented case, the Brazilians did not know how to investigate, let alone judge, a matter that had occurred at sea.

Realizing how difficult it was for Brazil to act in a case on which there was as yet no case law, Germany decided to ignore Brazilian sovereignty and made a decision that was as wise as it was controversial: it decided the case itself by appealing to its own maritime court – an instance that Brazil did not have at the time.

BRAZILIANS ARE JUDGED BY GERMANS

The German decision to judge a case that occurred in Brazilian waters and involved Brazilians put Brazil in an awkward position, as German judges would judge the country’s citizens.

Nevertheless, the trial was fair based on the principle that the judiciary is blind and stateless.

Three months after this improbable armed Brazilian attack on a simple passenger ship-without it being wartime, which would not be until nine years later, with the start of World War II-the, the verdicts came out.

The German court concluded that those responsible for the fortifications in Rio were negligent because they did not follow international norms, both in the deliberate firing (which should not have been directly on the ship but 200 meters away from it) and in the flagging, which followed the Brazilian code and not the international code, even though it was a foreign ship.

Why didn’t they use the radio?

Moreover, the German judges considered that the Brazilian officers of the two forts had ignored the possibility of radio communicating with the attacking ship before the attack.

But in an exemplary lesson in justice, the German court did not spare the Brazilian captain, who was convicted of bypassing the closure of the harbor, ignoring the warning shots, and not bothering to find out what those signal flags might mean, even if they were written in a different language.

For all this, the commander of the German ship was punished by banishment from his post.

In Brazil, there was only one administrative inquiry, in which only those in charge of the fort who had fired the shots were reprimanded.

A positive legacy for the country.

Five years after that tragedy in Guanabara Bay, the Baden stopped carrying passengers to Buenos Aires, was converted into a cargo ship, and when World War II broke out on Christmas Day 1940, was sunk by her own crew off the French coast to avoid falling into the hands of the British enemy.

But she left a positive legacy for the Brazilians.

Thanks to that stupid incident involving the German ship in the Sea of Rio de Janeiro and the Brazilian military’s inept response to it, the following year, Brazil began to establish its first administrative courts for the merchant marine, which was the first step toward the creation of the Maritime Court in 1954, which has since been responsible for adjudicating everything that happens in the Brazilian sea – including acts of war.

ANOTHER CASE INVOLVING A GERMAN SHIP

Ironically, one of the first cases investigated by the newly created Maritime Administrative Tribunals in Brazil was the mysterious sinking of another German ship, the freighter Wakama, also in the Rio de Janeiro Sea, in the early days of World War II – and less than a decade after the sinking of the liner Baden in Guanabara Bay.

The Wakama had left the port of Rio de Janeiro just four days after the start of the conflicts in Europe when it sent a distress call in the Cabo Frio area and sank.

Among the various theories put forward to explain the strange shipwreck, the most accepted was that the Wakama was attacked by British military ships that would have entered Brazilian territorial waters to hunt her down.

But why would a simple cargo ship be of such interest to the British that they sank it?

And why, decades later, did a unique German underwater rescue ship come to Brazil to search for the wreck of the freighter?

These are some of the doubts that hover over the sinking of the Wakama, which, unlike the Brazilian attack on the German ship years earlier, fortunately, claimed no victims.

There are a few mysteries that will never be fully resolved.