By Scott Squires*

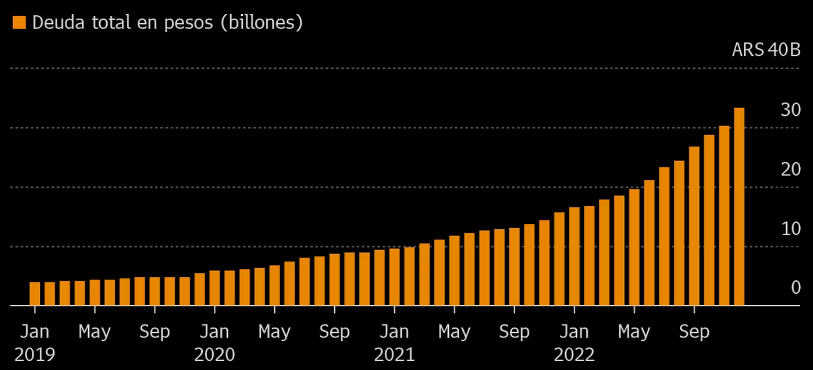

Cut off from global credit markets, Argentina’s government is selling more and more local currency bonds, piling up a debt burden that already amounts to $33 trillion (US$174 billion) and is increasing almost exponentially.

In one week, the Treasury will attempt to refinance $300 billion in debt, offering higher interest rates and shorter maturities to attract investors, as it has done in the previous four months.

For Fabricio Gatti, a portfolio manager at Novus Asset Management in Buenos Aires who holds this type of debt, that tactic will only work for a few more months.

“As we get closer to the end of the term, investors are going to be more skittish about a possible restructuring,” Gatti said.

“Investors expect the rollover to be maintained until the change of mandate, let’s say, it’s not assured the path yet.”

Argentina’s Economic Programming Secretary Gabriel Rubinstein said on Twitter that peso debt was sustainable and manageable, adding that Treasury debt held by private investors only represented 8% of gross domestic product.

A spokeswoman for the Argentine Economy Ministry declined to comment.

RISING DEBT

The Treasury refinanced debt in January and sold nearly $220 billion in new bonds.

Most of the securities sold under the administration of President Alberto Fernandez are tied to inflation, which has soared to an annual rate of nearly 100%.

So the skyrocketing inflation, rather than providing a large dose of debt relief, is further straining fiscal coffers.

DEBT BURDEN

Argentina posted a primary deficit of 2.4% of the gross domestic product last year.

Cut off from world markets since it restructured US$65 billion in foreign debt bonds three years ago, that deficit has to be financed in the local market.

And as the government tries to avoid printing money to curb inflation, the debt has a greater economic impact.

WALL OF DEBT

Argentina faces a wall of debt maturing starting in April, with an average of about $2 billion maturing monthly through the third quarter.

Creditors are increasingly reluctant to refinance those securities for an extended period for fear that the government will increase populist spending in the run-up to the October elections.

Rating agencies have already sounded the alarm, cutting the country’s local currency debt rating to selective default in January.

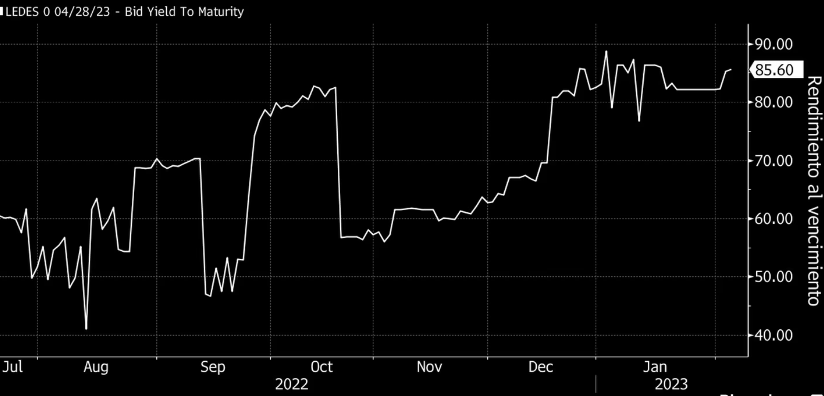

HIGHER RATES

As the debt burden increases and the threat of reprofiling looms, many private sector investors are waiting for the government to offer increasingly higher interest rates, said Juan Manuel Pazos, chief economist at TPCG Valores in Buenos Aires.

LONGER MATURITIES

The Treasury has not refinanced debt with maturities of eight months or longer since September, in stark contrast to earlier in the year. No debt sold on the open market in the past four months will mature after the parties hold primaries in August.

Four years ago, the left’s success in those same primaries sent Argentine assets tumbling.

“At some point, no carrot will be big enough for private sector investors to participate, and they will opt to stay on the sidelines,” Pazos said. “But we’re not there yet.”

THE SILVER LINING

Most of Argentina’s local securities are held by public institutions such as the state pension fund and state-owned banks, which generally refinance their debt.

Private investors, such as banks, investment funds, and insurance companies, are regulated, and many will be forced to continue investing, according to Adrian Yarde Buller, chief economist at Facimex Valores in Buenos Aires.

The fact that those investors have refinanced their debt has allowed Argentina to curb money printing over the past year as it tries to meet targets set in its US$44 billion program with the International Monetary Fund.

“Suppose investors stop refinancing debt in the second quarter, as some expect. In that case, the central bank will have to resume printing money, fueling inflation and increasing pressure on the government to devalue its official exchange rate,” according to Javier Casabal, fixed income strategist at local brokerage Adcap.

That, in turn, increases pressure for debt reprofiling.

If they fail to roll, the market will start to get nervous, and we may see more pronounced outflows in Mutual Funds,” said Javier Casabal.

“There are already redemptions, but for now, all manageable.”

*With the collaboration of Patrick Gillespie and Barbara Briceno

With information from Bloomberg