RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – The race for forecasts has already begun. Weeks ago, governments, international institutions, economists, think tanks and gurus embarked on a competition to explain tomorrow’s world as quickly as possible.

No one yet knows the ending of the crisis caused by Covid-19, the disease caused by the SARS-Cov-2 virus that in the space of four months has spread from China to the rest of the planet, killed over 155,000 people and confined half of humanity. It is not clear what the outcome of confinement will be, nor when a vaccine will ensure a return to normality.

No one knows for certain what normality will be within a few months. But the human instinct to move one step ahead -and the practical need to prepare for the new world and influence it- is the engine that drives an overproduction of documents attempting to shed light during the storm.

“It’s precisely when things are complicated and in motion that it’s useful to make predictions in order to see things more clearly,” says Bruno Tertrais, deputy director of the Foundation for Strategic Research, a think tank based in Paris, author of The Year of the Rat – Strategic Consequences of the Coronavirus Crisis, a clear and concise report on what is to come.

There are two groups in the prospective ferver. First, the group of those who believe that “nothing will be the same”, “we will inhabit a different world”, “it is the end of capitalism and globalization”. “It’s a profound anthropological commotion. We stopped half a planet to save lives: there are no precedents in our history,” said French President Emmanuel Macron.

The second group is the cautious ones. Those who, looking back at history, are suspicious of the dates that change everything. And those who argue that the coronavirus, rather than marking a historic divide, will simply heighten ongoing trends. Or even those who alert to the possibility of a return to the usual, business as usual, “to normal life,” as Donald Trump says.

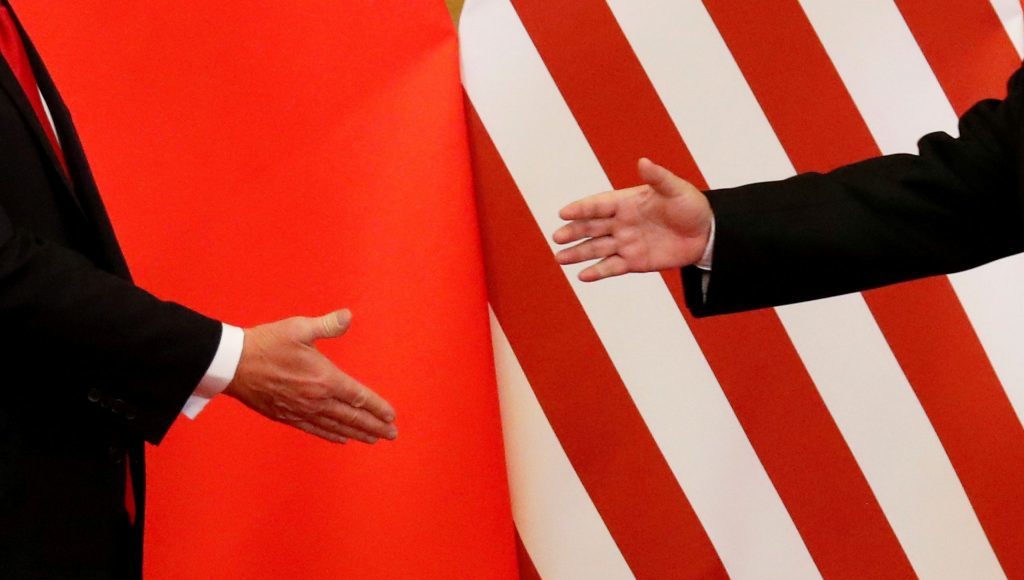

Tertrais outlines several trends: a setback in globalization; a decline of populist leaders coupled with the paradoxical success of sovereignty and border defense ideals; the return of the protective state; the height of surveillance societies; the risk of opportunistic actions by states and organizations: the temptation to fish in a roiling river. The latest trend, in the backwash of a very widespread prediction, is that no power -not even China- will come out strengthened.

Tertrais describes the coronavirus as a “strategic surprise” comparable to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 or the 2008 financial crisis. Not all “strategic surprises” produce the expected consequences: in 2001, after the Twin Towers and Pentagon attacks, a columnist for The New York Times predicted World War III. In 2008, French President Nicolas Sarkozy believed that the time had come for the “re-founding of capitalism”.

The present time may resemble the fall of the Wall: an event that fit into the spectrum of what was possible, although no one predicted it then; and a world blind for months. Everything could have turned out very well or very badly. “Nobody knew what was going to happen,” recalled historian Pierre Grosser a few months ago. “We thought the Soviet Union would implode, but we didn’t know how dangerous it could be.”

Nathalie Tocci, director of Istituto Affari Internazionali in Rome, speaks of a possible “Suez moment” for the United States, alluding to the 1956 Suez Canal crisis that hastened the end of the United Kingdom as a world power. “It is not that China will be the new empire, but it is a time when China’s global power is consolidated. It will have a power of attraction, a soft power, which is not exercised coercively,” she says.

In the report The International Order and the European Project in Times of Covid-19, Tocci draws two scenarios: one of closure -nationalism, protectionism, rivalry between powers and Chinese influence – and the other of openness that could lead to greater global cooperation. “If you ask me which of these two dynamics is stronger, I don’t know,” Tocci says.

“But I know there’s something that will make a difference: leadership. And today there’s virtually no such thing as leadership. Without leadership, I’m afraid we’re heading towards competition rather than cooperation.”

“We don’t know what will happen, but it’s worth thinking about it. It will depend heavily on how we go out and with what damage,” says Gregory Treverton, former director of the National Intelligence Council, the prospective US intelligence cell. His job was to imagine scenarios. And one of those he imagined was a pandemic in 2023.

“If you look at what was happening before the crisis, there was an increase in nationalism, in protectionism, in tension between the US and China, in disconnection between people and governments,” he reflects. “The question is how Covid-19 affects that. The answer is that in the short term, it will exacerbate it.”

Warren Hatch, president of the Good Judgement prognostic firm, believes that a geopolitical forecast -on the rise of China and the decline of the United States- should be circumscribed and divided into specific and verifiable questions: on the evolution of China’s GDP or China’s contribution to international organizations.

To the question of whether this crisis will change everything, Hatch answers: “Much of what we used to do that now seems unimaginable, like going to sporting events, I believe we will do again: we will devise something. On the other hand, there are things that were previously changing and will quicken: the concept of working from home, for one, or seeing the doctor from home over the Internet”.

Among all the predictions flowing about the world that will emerge from this coronavirus crisis is one that can be advanced without fear of being mistaken: it will be a world obsessed by pandemics. After the 2001 attacks, terrorism became the center of gravity, which did not allow perception of other threats.

The same could happen now, with pandemics in lieu of terrorism. “There is indeed a risk,” Tertrais says, “that in the next five years the pandemic will be considered the number one risk and that the others will be less perceived”.

Climate change is mentioned among the threats. Or further pandemics. “This is a general essay,” says Treverton. “Imagine a pandemic as lethal as Ebola and as transmissible as Covid-19. I see no other such threat.”

A “harsh competition” according to the French perspective

“The post-crisis world is prepared during a crisis, not in the end,” says a report by Quai d’Orsay’s Analysis, Forecasting and Strategy Center (CAPS), a kind of internal think tank of the French Foreign Ministry.

The report, released in late March by Le Monde, does not define France’s official policy, but points to strategic lines of thought in the face of the “harsh competition” that is looming. The starting point is that the next day will be troubled and that the prolegomena are at stake at these times.

There are multiple threats: from political stability to social peace. The report alerts to “the Chinese narrative”: the potential future attractiveness of its model, reinforced by propaganda. For this reason, it is necessary “not only to develop a counter-narrative, but to be able to rely on an eloquent balance and to stress the differences in method”.

And he adds: “Because, at the end of the day, history is written by the victors”. The power voids and the exploitation that powers such as China or Russia can make may lead to “an acceleration in the redistribution of cards”. The authors do not engage in the debate about whether we are facing a radical change or a reversal to the inertia of the past.

“A crisis of such magnitude is always an opportunity for profound realignments,” the paper says. “But it does not automatically imply any of these realignments. In the end, it is politics that imposes them, or the one that is not up to the task”.

Source: El País