By Scott Squires

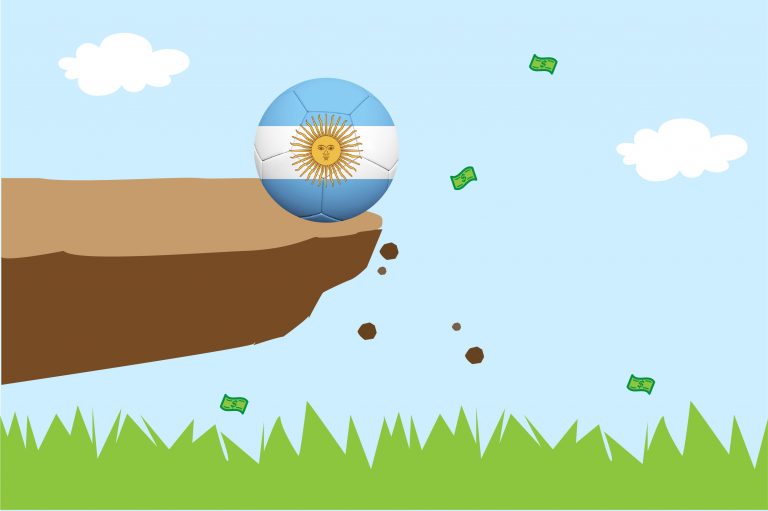

Argentina’s attempts to keep its currency from devaluing further are leaving the central bank short of reserves, according to estimates.

The country has already spent all of its international liquid reserves, adding another US$1 billion, according to Buenos Aires-based consultancy 1816 Economía & Estrategia, raising risks as the nation faces a historic drought and a looming recession.

With no cash available, questions arise about how long the government can continue to defend the peso from total collapse.

What is at risk is that a currency devaluation will fuel a 104% inflation and exacerbate high levels of social unrest ahead of October’s presidential election.

“Fewer reserves generate more pressure on the exchange rate, which in turn generates more inflation pressure,” said Fernando Losada, managing director at Oppenheimer & Co.

“I don’t see any possible scenario in which inflation falls below triple digits this year.”

Argentina has faced difficulties for decades in accumulating and maintaining its international reserves at healthy levels and has used large amounts of cash to combat rising prices and juggle foreign bond obligations.

Technically, the nation now has less than US$34 billion in total foreign reserves, but most of it is locked up in less liquid assets, such as gold, swap lines of credit with China and the Bank for International Settlements, and the dollars that Argentines hold in their savings accounts.

That’s a problem for a country that needs ready cash to spend.

Argentina’s foreign currency liabilities already exceed total reserves by about US$1 billion, the worst ratio since the country was rocked by the economic crisis in the early 2000s, according to last week’s report from the firm 1816.

Argentina has been tapping its dollar reserves to stem a slump in the peso’s parallel market exchange rate, replacing the government’s official exchange rate amid draconian capital controls.

Last week alone, the Central Bank sold around US$470 million to support the currency in the parallel markets, said Fernando Marull, an economist at Buenos Aires-based consultancy FMyA.

It has been difficult to measure the success of the government’s intervention.

Last month, the unofficial peso lost about 13% against the US dollar and was down 33% this year, the biggest drop in emerging markets.

President Alberto Fernández has tried to strengthen reserves by forcing export dollars into the central bank’s accounts and accepting cash injections from the International Monetary Fund.

But those measures are failing.

And Fernández, who has already withdrawn his re-election candidacy, has no assurances that talks to rework a US$44 billion program with the IMF will result in advanced loan disbursements to help ease the situation.

A spokesman for Argentina’s central bank said the market’s calculation of net reserves does not adequately reflect its balance sheet because it does not consider other financing sources, such as a currency swap line with China.

Meanwhile, the authorities have opted for other emergency measures, including using the China swap to finance US$1.8 billion of the country’s imports.

It also works with Brazil to boost bilateral trade with credit lines in reais, allowing it to bypass the dollar.

For Argentines, uncertainty is palpable.

Scarred by the Central Bank’s decision to freeze access to dollar savings during the 2001 economic crisis, many Argentines are already withdrawing cash from their savings.

They withdrew more than US$1 billion in deposits from the banking system from the end of March to the end of April.

Moreover, there is little sign that reserves can be rebuilt in the short term.

The worst drought in a century has eliminated any chance of an influx of cash from agricultural exports before the election.

“The risk of having liquid reserves in negative territory is that the central bank won’t have the dollars to deal with an even larger outflow of foreign currency deposits,” said Juan Sola, an economist at BancTrust & Co. in Buenos Aires.

With information from Bloomberg

News Argentina, English news Argentina, Argentine economy