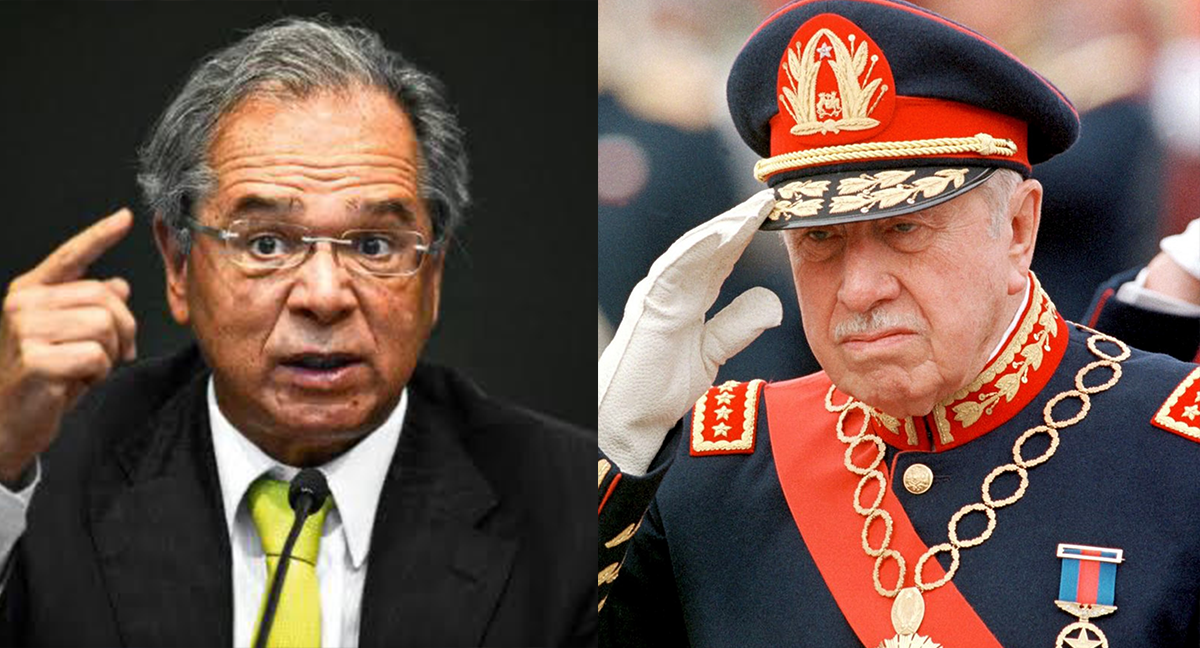

RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Currently privatized, Chile’s health system was once public and served the entire population. The change occurred during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990), whose economic policy came from the same liberal school as the current Minister of Economy Paulo Guedes.

Speculation about a potential privatization of the SUS (Brazilian Unified Health System) gained prominence last week after President Jair Bolsonaro issued a decree that enabled studies for public-private partnerships for the construction and administration of UBS’s (Basic Health Units).

After negative repercussions, the President revoked the measure but said he will issue a new decree next week. Unlike what occurred in Chile, Guedes denied that he intends to privatize the SUS. According to researchers, the liberal changes have led to improvements in health rates there, but have increased social inequality.

Pinochet’s liberal dictatorship

The Chilean National Health Service (SNS) was founded in 1952 based on the British NHS, considered the first unified health system in the world. When it was established, it had no universal coverage, its funding was linked to Social Security contributions.

The SNS became more similar to the Brazilian SUS between the late 1960s and early 1970s, under Salvador Allende’s government. According to a study by Fiocruz (Oswaldo Cruz Foundation) researcher Maria Eliana Labra, at the time the system covered 100 percent of the population on public health issues and provided 90 percent with medical and hospital assistance. Only the Armed Forces, which had their own health systems, as they still do nowadays, were left out.

With the Chilean military coup in 1973, Pinochet began to adopt a liberal agenda, having, as two of its main pillars, the opening to foreign markets and privatizations. Among the measures adopted were the end of a collective social security fund, such as the Brazilian INSS, and the conversion of the SNS into SNSS (National Health Services System), a body that provided 27 health services independently.

“The goal was to introduce the private sector in health, following the neoliberal guidelines organized and endorsed in the 1980 Constitution, where the right to health was perceived as the option to choose which health system to join,” the Chilean organization ‘Salud para Todas y Todos’ (Health for All) stated.

Two contribution funds were created: the FONASA (National Health Fund), which offers public assistance with the option of private contracting, and the ISAPRE (Health Insurance Institutions), which is entirely private.

In practice, according to Chilean and Brazilian researchers from UEFS (State University of Feira de Santana), this represented a division between “the people with the highest salaries, who could afford their health plans in the ISAPRE market”, “the average sectors, who could choose FONASA’s free option for private providers, making copayments” and, finally, “the sectors with the lowest salaries, or unemployed, who were served in the state health units free of charge.”

To be part of the third group, one must demonstrate a situation of poverty and the resulting inability to pay for the funds. “Health in Chile is no longer a universal right, but rather the option to choose between these two subsystems with many contrasts,” states ‘Salud para Todos y Todos’.

Inequality has increased

In the study published in 2001, Labra points out that, at the time, the Chilean health situation was better than the Brazilian one. In her opinion, the neoliberal changes contributed for its health indicators to be “close to the levels of more developed countries”.

On the other hand, the end of universality aggravated inequality in the country. Currently, a Chilean family spends on average 33 percent of its income to access health care, according to Salud para Todos y Todos, while other OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) member countries’ index stands at 8.5 percent. Furthermore, 78 percent of the population depends on the FONASA while only 17 percent can afford the ISAPRE.

“The processes that have led to the duality of Chile’s health system not only reproduce social inequalities as a whole, but also amplify them, resulting in the maintenance of high direct disbursement rates, which contributes to insecurity and lack of protection for both populations but certainly with greater impact on the less favored sectors,” concludes the UEFS study.

Guedes comes from the same school

Paulo Guedes is from the same ultraliberal school as the idealizers of the Pinochet dictatorship’s economic plan. It was at the University of Chicago in the United States in the 1970s that the current Minister of Economy met the “Chicago Boys,” as the dictator’s economists, followers of Milton Friedman, became known.

It was through them that Guedes started teaching at the University of Chile in Santiago in the early 1980s, invited by Jorge Selume, then director of the School of Economics and Business and director of Pinochet’s Budget. The university, led by the military, was the dictatorship’s center of economic policy-shaping.

Unlike his boss, Guedes never made any positive public references to the Chilean dictatorship. “I knew zero of the political regime. I knew there was a dictatorship, but to me, that was irrelevant from an intellectual perspective,” he told Piauí magazine in 2018, speaking of the time.

Now, Chile points to a real possibility of changing this system. On October 26th, 78 percent of Chileans voted in a popular referendum to end the 1980 dictatorial Constitution and decided on a new Magna Carta – the first to be formed by an assembly elected by popular vote, like Brazil’s in 1988.

Guedes has already stated that privatizing the SUS would be unthinkable and has never been under consideration. After the decree’s negative repercussion, Bolsonaro revoked the measure last Wednesday, October 28th, but has already stated that he will issue a new one next week.

Source: UOL