RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – The authorities and the population of Brazil may have some idea of what is coming with the coronavirus spreading in a megalopolis like São Paulo, because they are a few weeks behind Wuhan or Madrid.

But coupled with the infinite uncertainties surrounding the crisis, the country is facing the threat “with an aggravating factor: there is no model as to how the virus spreads in the favelas,” cautioned biologist and publicist Atila Iamarino last week.

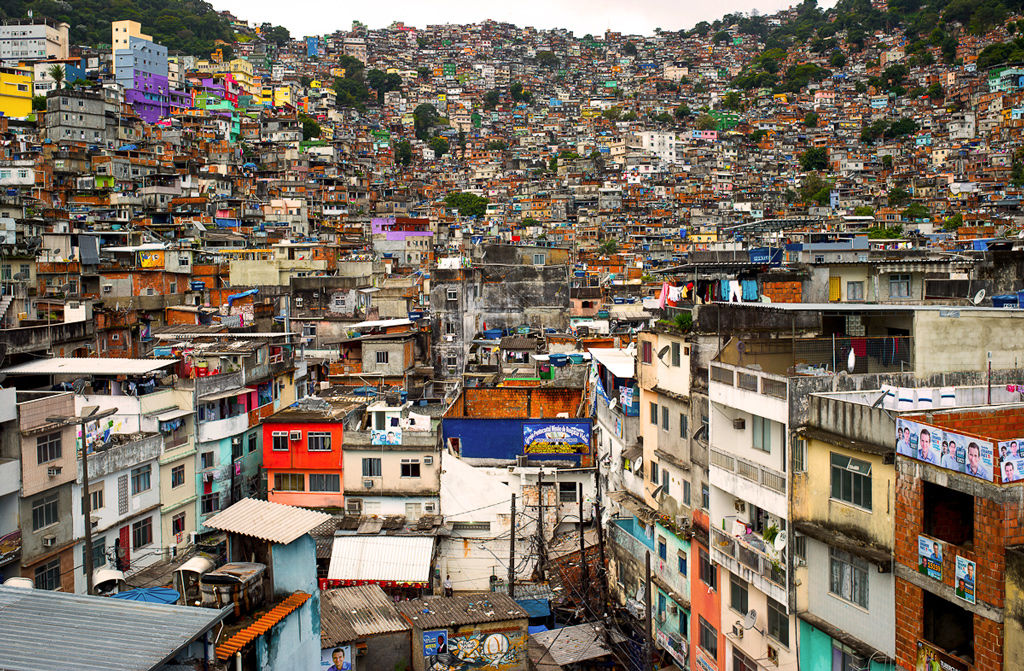

For the 30 million Brazilians who lack basic sanitation or the 11 million who live in thousands of favelas spread over a territory twice the size of the European Union, it is difficult to follow the simplest health recommendation – washing one’s hands often with soap and water – and hand sanitizer is an unaffordable luxury.

And working at home is a fantasy for families who share one or two poorly ventilated rooms or when feeding their children requires going out on the streets to sell sweets or to care for others’ babies or gardens.

Cases have already been confirmed in favela communities in Rio de Janeiro, as the advancing pandemic gains speed. By Saturday afternoon, the official total in the country was 432 deaths and 10,278 infections.

In these overpopulated communities where few trust the authorities, where the state only surfaces in a police uniform, where the most basic infrastructure is lacking, and where people live on what they earn in the day, fighting the coronavirus is a very delicate mission that troubles leaders; as a result, civil society has set to work in an attempt to stave off disaster.

“The crisis is already affecting us very violently and we know that here it will infect many people,” explains Gilson Rodrigues, president of the NGO Union of Residents and Trade of Paraisópolis, by telephone. He says that, although it has taken several days, the once vibrant commerce of this favela with 100,000 inhabitants in São Paulo is now closed, complying with the social isolation measures recommended by the Ministry of Health and the state government.

These are drastic measures, in line with WHO guidelines to face the health threat, which President Jair Bolsonaro considers excessive due to its brutal impact on the economy, because “hunger kills more than the virus”.

Persuading residents to reduce contact with other people to stop the contagions was not easy, because in Paraisópolis “some don’t believe that the virus will come, and others don’t believe it will be as violent,” says Rodrigues. Cosme Filipsen, who lives in the Morro da Providência favela in Rio, says by phone that until a few days ago, a good number of his residents were still gathering for a barbecue and a beer.

This popular disbelief is no surprise considering that President Bolsonaro leads those who considered the Covid-19 “just a flu” and continues to encourage the population to fully return to economic activity, contrary to the criteria of Health Minister Luiz Henrique Mandetta.

The Minister, a doctor, alerts that as long as there is no vaccine or a sufficient number of hospital beds, ventilators, and masks, the most effective course of action is to remain at home. “In addition to being ineffective against the pandemic, Bolsonaro is endangering us all,” Filipsen insists.

The virus, which seems to have arrived in Latin America with a Brazilian businessman who has returned from Milan, advances in a country where great social inequality complicates the battle even more.

Nísia Trindade Lima, president of Fiocruz, one of Brazil’s leading institutions in public health research, explained in a recent interview that Covid-19 “is coming in fast, but it finds itself in a reality where we have a high population density and in very vulnerable housing conditions, as is the case with many of our peripheries and favelas in all of Brazil’s urban centers. In addition, we have difficult urban mobility, with crowded transportation”.

Filipsen says that his recent protests on social media against the water shortage in his community had repercussions in the media and that, finally, water supplies were restored in the area, which “had been without water for three months before the pandemic”.

In addition to the concern over the absence of basic sanitation – “despised by politicians because it doesn’t feature in electoral campaigns,” says the leader of Paraisópolis’ residents – there is an even more pressing concern, the economic calamity: traders lost their income with the closure of stores, and many janitors or babysitters who worked in upper-middle class neighborhoods “were fired or sent on unpaid vacations”.

As direct economic aid announced by the federal, state, and municipal governments has not yet materialized in Brazilians’ pockets, neighborhood associations from countless communities have sought allies to distribute food to those most in need, in addition to advising people of the magnitude of the risks and how to prevent them. In Paraisópolis, they are even building a makeshiift field hospital.

Source: El País