RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – The Brazilians have never been so anxious to see the country grow again. No wonder. After all, these are years of economic stagnation with real consequences for the population. In practice, the low growth rate means that companies are increasing their production very little from one year to the next. As a result, income does not increase and employment does not grow, harming the lives of thousands of people.

This situation is nothing new. Recession cycles are part of any market economy. However, attention is drawn to the fact that the recession period has lasted longer than usual. On average, in the past, stagnation would last three years, and the economy would then grow again. Now stagnation has lasted almost six years.

The previous years were so bad that many seem content with a growth of around 2.3 percent for 2020, according to the Central Bank’s Focus projection. Faced with this projection, the question everyone asks is: why not three or four percent? Why is the projection within the 2.0 to 2.5 percent range, despite the government’s fiscal effort and the lowest level of interest rates in history?

With the lower cost of capital, shouldn’t there be an increase in consumption and in the level of investment of companies, positively impacting the GDP? The answer to this question is not self-evident and, today, economists, investors, and managers raise some assumptions as to why growth has not yet been achieved.

The first assumption is that growth will come with some time lag. Under this premise, the effects of the welfare reform and monetary policy approval will not be immediate, but will certainly come for the real economy. This is corroborated by a number of indicators that show economic rebound.

A second assumption is that Brazil’s growth has always been highly dependent on foreign investment. And, with the prospect of a new global recession, enhanced by the coronavirus epidemic that exposed Chinese vulnerability, foreigners have become more averse to investing in Brazil.

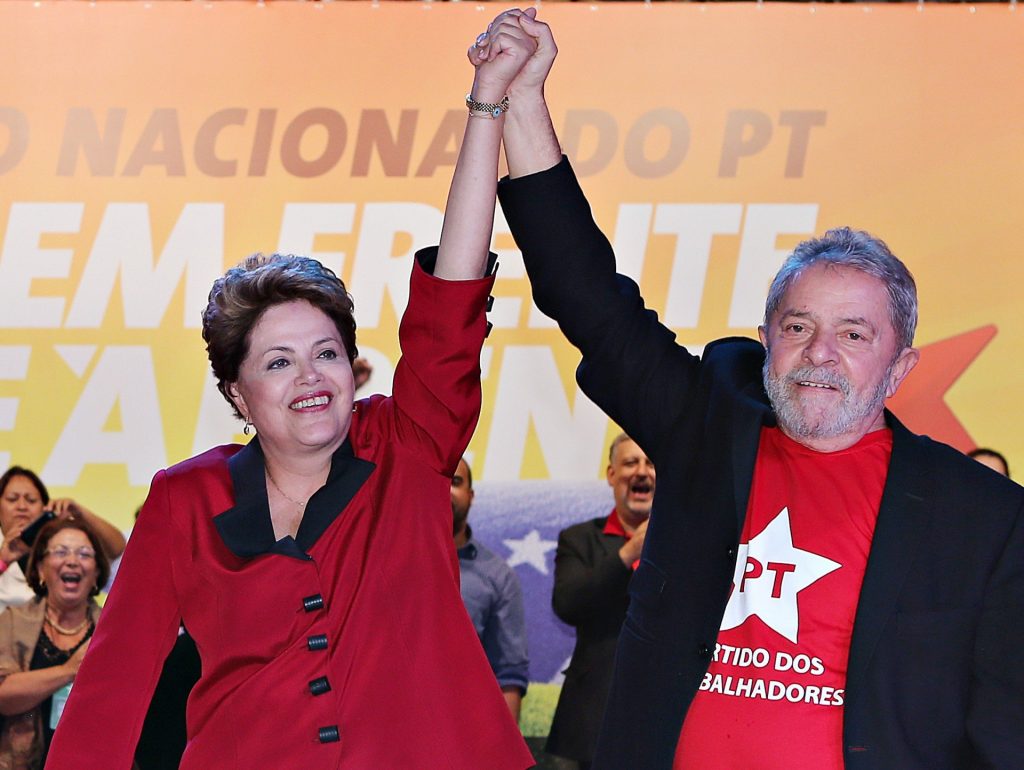

Another assumption refers to the change in growth dynamics in relation to the past. In the past, Brazil’s growth was highly dependent on state incentives, whereas now it depends more on private initiative. In this regard, we should have lower growth, but healthier and more sustainable, without the side effects (increase in debt) such as those generated by the Lula and Dilma administrations.

A last assumption is that the tensions between the Executive and Legislative Branches lead to a climate of uncertainty regarding the approval of other reforms (administrative, fiscal) essential to generate more significant economic growth in the medium and long term.

Regardless of which assumptions explain the slow economic rebound, it is urgent that Congress understand that the passing of reforms, which will benefit the Brazilian population, must take precedence over electoral interests, such as the concern that the measures will favor Bolsonaro’s reelection by improving the economy.

Ultimately, Congress represents the Brazilian population, and the country’s interests must outweigh patrimonialism which has historically penalized a more solid development of Brazil.

Source: InfoMoney