RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – A new research conducted in co-participation by the Institute of Tropical Medicine (IMT) and the Hospital das Clínicas (HC), both from the São Paulo University (USP) School of Medicine (FMUSP), which diagnosed two new cases of Sabiá virus (SABV) infection in 2019, has deepened the investigation on this Brazilian hemorrhagic fever.

Previously, only four infections of this type had been detected in Brazil, the last of them more than 20 years ago. Both diagnoses were made in the middle of a yellow fever outbreak in the country’s southeast region.

“We did this study during the yellow fever epidemic, so in the cases where we couldn’t close the diagnosis, we went after other viruses,” explains Dr. Ana Catharina Nastri from the Infectious Diseases Division at HC-FMUSP. “To our surprise, we found these two cases, which are extremely rare.”

According to her, advances in pathological anatomy, especially in electron microscopy, have allowed a more in-depth study of the Brazillian mammarenavirus, or Sabiá virus, bringing new information regarding its clinical manifestations, histopathology, and the possibility of hospital transmission.

The findings were published in an article in the Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease journal in May this year, with the physician Nastri as the first author and the supervision of professor Ana S. Levin from the Department of Infectious and Parasitic Diseases of FMUSP.

SABIÁ VIRUS

The pathogen’s name refers to the Sabiá neighborhood, located in the municipality of Cotia, in Greater São Paulo, where the first victim is suspected of having been infected.

Although several types of Mammarenavirus are described in different South American countries, SABV is characteristic of Brazil.

“Some of these viruses have the viral cycle better known, while our Sabiá virus has very little data,” says the doctor. “We still don’t know what its reservoir is in nature, the form of transmission, and whether there would be infection through inter-human contact.”

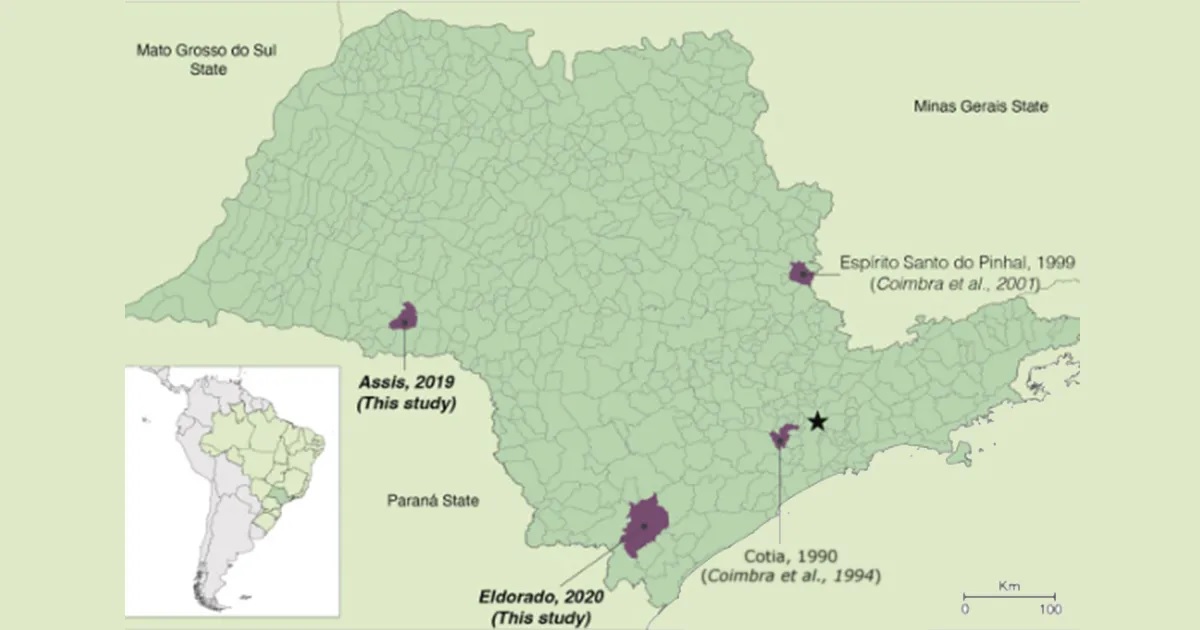

Previous to the study, only four SABV infections had been recorded. One occurred in the city of Cotia in 1990, and another in the city of Espírito Santo do Pinhal in 1999, both located in the rural area of São Paulo state.

In both cases, the infection affected rural workers who died due to complications of hemorrhagic fever. The other two infections occurred in laboratory workers who were probably infected while handling the virus. Both survived.

“CASE A AND CASE B”

The two new cases detected, called in the study conducted at the Hospital das Clínicas “Case A and Case B”, occurred in the cities of Sorocaba and Assis (in the interior of São Paulo state) respectively.

Both patients were admitted to the Hospital das Clínicas (HC) with a diagnostic hypothesis of a severe case of yellow fever.

The first was a 52-year-old man hiking in the forest in the city of Eldorado (170 km south of São Paulo City) who started showing symptoms such as muscle pain, abdominal pain, and dizziness.

The next day he developed conjunctivitis, was medicated in a local hospital, and released. Four days later, he was again hospitalized with a high fever and drowsiness. Yellow fever was suspected, and he was transferred to the Hospital das Clínicas.

During hospitalization, his clinical condition worsened until he was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) ten days after the onset of symptoms, with significant bleeding, renal failure, decreased level of consciousness, and hypotension, and he died two days later.

Case B is a 63-year-old man, a rural worker from Assis (440 km west of São Paulo City), who presented with fever, generalized myalgia, nausea, and prostration.

The symptoms worsened, and eight days later, he was admitted to HC with depression of the level of consciousness and respiratory failure requiring intubation.

Severe left ventricular dysfunction (drastic reduction in the pumping function of part of the heart) led to refractory shock and eventual death 11 days after the onset of symptoms.

WHAT IS KNOWN AND WHAT REMAINS TO BE KNOWN

To make the diagnoses, the scientists used the metagenomics technique, which allows the identification of still unknown viruses by extracting, replicating, and eventually sequencing the genetic material of the infectious agent.

This material is compared to other organisms in bioinformatics databases, with information on pathogens worldwide.

By relating the virus found in the patients to other types of Mammarenavirus and verifying the compatibility of the finding with clinical practice, it was determined to be SABV.

In the analysis of the two fatal infections in the study, the researchers identified symptoms analogous to those recorded in the cases of the 1990s.

“The clinical part is very similar to what we had seen before, and among the two new cases, the manifestation was also very similar,” says Ana Nastri.

In all cases, there was significant involvement of the liver and organs associated with the production of defense cells, which may have facilitated the appearance of secondary infections, making the initial diagnosis more complex.

As for the geography of the infections, the four recorded cases had infections occurring in rural areas as a common point.

“We inferred, based on the other Mammarenaviruses in South America, that the person is probably contaminated by inhaling viral particles, perhaps from rodent feces. But this is not proven to be precise because we have very few cases described,” says Ana.

The doctor also alerts that, precisely because the rural areas have fewer laboratory and diagnostic resources, some cases may have evaded clinical analysis, making it impossible to have a complete picture of the Brazilian hemorrhagic fever.

“We don’t know if there really aren’t milder cases, as in yellow fever, which has from the severe case to those who have no symptoms at all.”

One significant difference from previous reports of the virus relates to the incidence of hospital transmission. The IMT and Hospital das Clínicas scientists found no such infection during contact tracing.

“This shows that with the usual precautions, such as mask, glove, glasses, and apron, there was no transmission, and puts us a little more at ease about our virus,” says Ana Nastri.

She points out, however, that it is still impossible to reach a conclusion since there are only two cases.

With information from the FMUSP Press Office