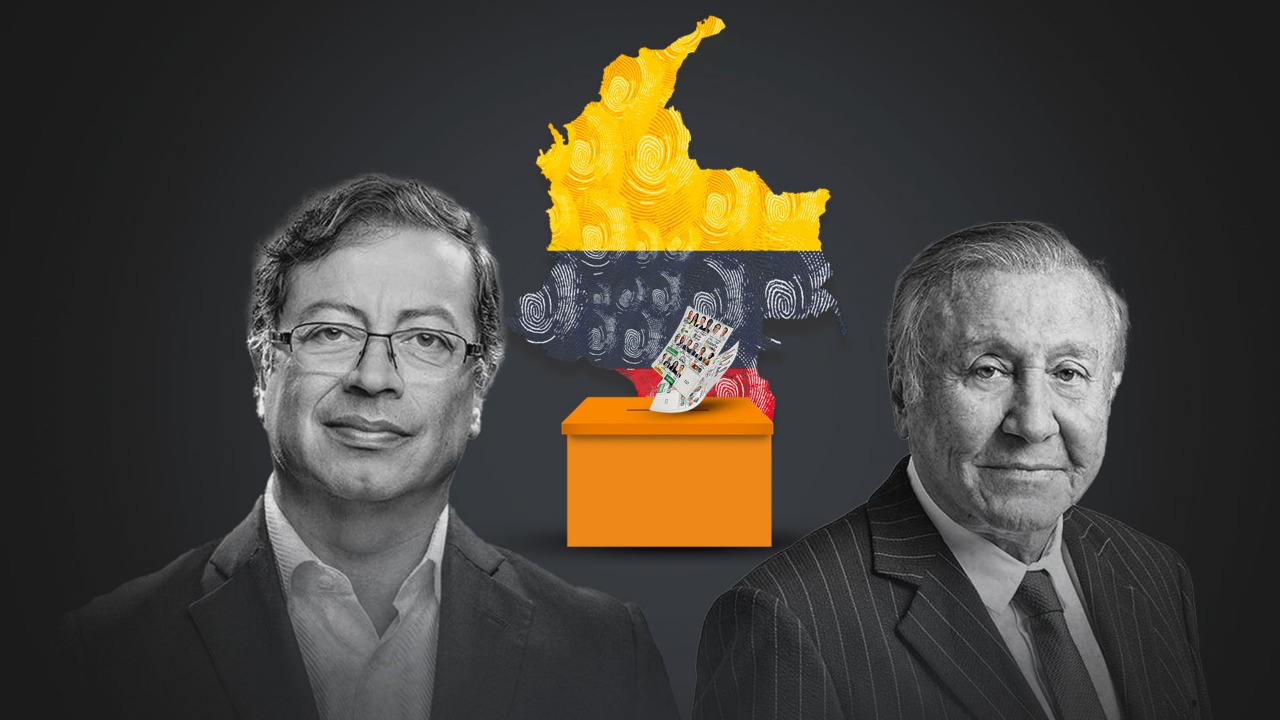

RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Colombians will star this June 19 in a presidential ballot that will change the country’s history, when they choose between leftist senator Gustavo Petro and businessman Rodolfo Hernández, an “outsider” with conservative ideas, which displaced from the second electoral round, the liberal and conservative party structures that have so far dominated the political life of Colombia.

Although the Congress was already formed in March, still influenced by those two traditional parties, the new president will mean a radical change in the country: either because Petro (62 years old) crowns his third attempt to bring the left to power for the first time, or because Hernández (77) absorbs the vote of the center and right that he surpassed with his simple anti-corruption and anti-establishment speech (“If it is populist, do say ‘don’t steal’, yes then I am populist and I don’t care”, he proclaims).

Read also: Check out our coverage on Colombia

In the first round of May 29, with a participation of 55% of the electorate, Petro (of the leftist alliance Pacto Histórico) obtained 40.3% of the votes, a level of support that culminates for progressivism his support for the Agreement of Peace of 2016 that demobilized a large part of the leftist guerrilla, the bulk of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

Contrary to all initial forecasts, the right wing represented by the uribista Federico Gutiérrez (23.9%), former president Alvaro Uribe’s designated successor (2002-2010), and the center that nominated Sergio Fajardo (4.2%) were buried under an avalanche of votes for Hernández (LIGA, 28.1%), the “Colombian Trump”, a real estate tycoon whose main public experience is having been a councilor and mayor of Bucaramanga (east of the country) between 2016 and 2019.

Immediately, Gutiérrez anticipated his support for Hernández to add his votes (mathematically, 52% would be enough) and stop Petro’s access to the Presidency. But the eccentric businessman, who based his campaign on attacks on politicians through social networks like Tik Tok, took care of his outsider profile and denied a natural association with the traditional right: “Zero Uribe, zero Gutiérrez, zero all… I receive your votes, but I don’t change the speech”.

“In many places in Colombia, a parochial and conservative political culture prevails, which traditionalist elitism has neither known nor wanted to understand. Its excesses in the patrimonialization of the State, and the image of continuous looting, the product of a corruption as endemic as it is patronage, provides an ideal setting for the anti-establishment and anti-corruption discourse that, demagogically, Hernández raises”, summarized an analysis of the newspaper El Espectador.

But the electoral mathematics between candidates is not automatically transferred in this case either, as always happens from first rounds to second rounds.

Hernández is a conservative shield against Petro, but his attitudes -trumping a councilman who denounced him as mayor-, ideas -considering Adolf Hitler a “thinker” or that women should stay at home- and proposals -delivering free drugs to consumers to cut supply- can scare away a key part of the Colombian conservative electorate, rather than attract it with his ideas of reducing salaries and expenses of public officials or massively building social housing (he made his fortune and fame financing that type of enterprise).

Meanwhile, Colombians voted in the first round and will do so again in the ballot, with the fresh memory of the 2021 National Strike, almost two months of protests (more than 40 dead and losses officially estimated at about US$3 billion) between April and June that forced the Duque government to back down and displace the Minister of Finance, Alberto Carrasquilla.

THE PROPOSALS

Hernández made the fight against corruption his battle horse (his party is called the League of Anti-Corruption Governors – LIGA), a simplism that he claims, even though he himself was accused in several cases and has a slope for favoring his son in U$S 1.5 million in a contract from the mayor of Bucaramanga, where his greatest achievement was to reduce the state apparatus and recover the city’s surplus.

“Everything has to do with the theft of public money, if it is stolen nothing can be done and necessities accumulate that are not resolved, and lead to violence. And to solve it, money is needed, but there is no money because it is stolen, it is a vicious circle that we are going to break. If corruption is not defeated, nothing can be done. For me, the foundation of the Government that we are going to preside over is corruption”.

But his platform expresses broader possibilities, linked to the traditional right, such as reducing the State and lowering taxes, although raised under the antinomy centrist urban elite / Colombian rural interior and with a bias of pragmatism that translates into 35 themes and 100 lines of work. “The backbone of my government is the activation of the countryside, which generates a lot of work”, he said.

In social terms, it proposes granting a universal basic income equivalent to US$250 and another to all older adults (without explaining how it will be financed), forgiving student debts, and establishing price controls throughout the health care chain to encourage the national medicine industry.

A coincidence with Petro, however, is his commitment to reaffirm and consolidate the Peace Agreement, with an “approach process” although he has not yet opened a phase of negotiations with the National Liberation Army (ELN), which declared a truce of its armed struggle during the elections, as well as reestablishing commercial relations with neighboring Venezuela governed by Nicolás Maduro.

Petro goes one step further and proposes to dismantle “the successor groups of paramilitarism and linked to drug trafficking” through judicial submission.

In addition to a radical difference in the approach to the fiscal issue and taxes -Hernández wants to lower them (the IVA, by half) and Petro proposes to increase them with a progressive criterion- the two candidates contrast on a central issue in the modern history of Colombia: the illegal production and trafficking of cocaine and other drugs.

While Hernández lacks specific proposals against organized crime related to illegal drug trafficking (only legalizing cannabis use), Petro prefers to end prohibitionism in general, which he considers a failed model, and proposes managing within the framework of a paradigm that decriminalizes the producers of rural populations, with substitution programs that weaken the entire chain of cocaine.

In matters of economy, the left and progressivism in general intend to govern Colombia with a balanced budget that “allows for a State with efficient spending”, in such a way that the funds for employment, distribution and growth “have the same importance than paying the debt”.

The left dreams of reducing the current weight of extractivism -agriculture and mining- and achieving a redistribution of the land in favor of small producers. “A progressivism cannot be based on the extraction of raw materials that mean the end of humanity. It is a contradiction”, says Petro, and differs from the movements led by Hugo Chávez or Rafael Correa in the 2000s.

Petro is preparing an expense of COP$19.5 billion, with a tax reform of COP$50 billion, half of which will serve to reduce the fiscal deficit. At the same time, he promotes the unification of the pension system, today partly state-owned and partly private, to basically turn it into one public system.

Last April, ECLAC lowered by one point, to 3.3%, the growth forecasts for the economies of Latin America and the Caribbean due to the war between Russia and Ukraine, and aggravated by higher inflation and a slow recovery of the job.

In this context, the regional body projected 4.8% expansion for Colombia, whose economy in 2021 had grown at the fastest rate in more than a century (10.6%), due to the control of Covid-19 and the increase in oil, coal and coffee.

Production then returned to pre-pandemic levels, although with inflation of almost 10%, twice the target set by the Central Bank of Colombia, and unemployment of 12.1% (2.9 million), which is even higher among young people (14%).

In 2018, Petro had defined as a central problem in Colombia “that capitalism has not been developed… what we propose -he said then- is the development of democratic capitalism.” “I have been on the left and I do not regret it. But I am not proposing a left program. I am not proposing a socialist program”, he emphasized.

Four years later, the candidate of the Pacto Histórico reaffirms himself and insists on “changing the economic model”, which includes a reform of the Central Bank, which he considers dependent on the elites and to which he proposes adding the representation of diverse economic organizations of the productive system.

In education, the Pacto Histórico promotes free public higher education and a total eradication of illiteracy, with kindergartens free of charge. And in environment, it proposes pacts to protect Colombian jungles and forests, stop the loss of biodiversity and frame the country in the 2015 Paris Agreement.

With information from El Economista