RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – According to experts, the most important consequence of the definition of an “ecological state” would be the duty of the state to establish a balance between human activities and nature through all its institutions, not only those that deal with environmental issues.

However, the evaluation of this issue causes debate among experts, as some consider it an “etatist” vision that does not take society into account when it comes to environmental protection. Others point out that it is “a necessary step” to “create awareness that will allow us to preserve natural systems.”

Read also: Check out our coverage on Chile

WHAT IS CHILE REVIEWING?

The definition of Chile as an ecological state is one of the innovations in the constitutional text proposed by the Convention. Article 1 enshrines that the country is “plurinational, intercultural and ecological.”

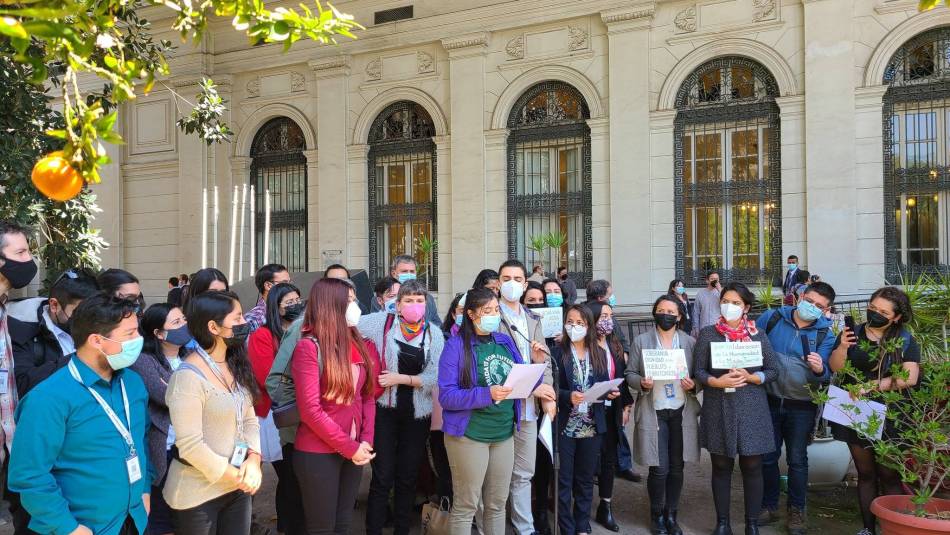

An earlier article in this column discussed how the presence of more than 30 Convention members, known as “eco-constituents,” has strongly promoted the environmental agenda in the Convention’s work. Most of them make up the Environmental Commission, which, despite the initial rejection of its report, has already succeeded in including articles such as the one that establishes the rights of nature or the one that establishes the unfitness of water in the proposed Constitution.

The coordinator of the Commission, Juan José Martín, declared after the approval of the first articles that “from today, this Constitution is an ecological Constitution,” which is in line with the recent entrenchment of the concept of the ecological state.

Therefore, in its Constitucheck, Watchdog Pauta examined the implications of classifying Chile as a country with these characteristics and what changes might result in practice.

WHAT DOES THE PROPOSED CONSTITUTION SAY?

In the “Constitutional Principles, Democracy, Nationality and Citizenship” chapter of the proposed new Constitution, Article 1 establishes the ecological character of the state. It states that “Chile is a social and democratic state governed by the rule of law. It is multinational, intercultural and ecological.” Among the “intrinsic and inalienable values” established in this article is the “substantial equality of human beings and their indissoluble relationship with nature.”

In addition, the chapter on the environment, the rights of nature, natural resources, and the economic model states that nature has rights. Article 4 guarantees “that its existence, its renewal, the preservation and restoration of its functions and its dynamic balance shall be respected and protected.” It states that it is the responsibility of the state to ensure and promote it “in accordance with the Constitution and the laws.”

AN ECOLOGICAL CONSTITUTION

The non-governmental organization Fima is one of the main organizations pushing the idea of an ecological constitution. In June 2021, they published a study that listed five reasons why Chile should have a Magna Carta with these characteristics: the current state of the environment and the ecological crisis, the climate crisis, ethical obligations to future generations and nature, socio-environmental conflicts, and meeting the demands of citizens.

The study concludes that “finding solutions to the climate and environmental crisis we are experiencing and to the socio-environmental conflicts caused by the exploitation of nature is essential, and it is also necessary to respond to people’s demands.” Therefore, they propose to promote an “ecological constitution based on the notions of justice, participation and the inherent value of nature.”

This approach has permeated much of the Convention’s work, and the “eco-constituency” bloc has advanced the environmental agenda in the proposed Magna Carta. Among the measures already approved by the plenary is the inclusion of nature as a legal subject, which would represent a radical change in the way environmental protection is currently considered in Chilean legislation.

Ricardo Irarrazábal, former undersecretary of the environment in the first government of Sebastián Piñera and current professor of environmental law at Catholic University, says it is important to distinguish between the environment and ecology. “The environment has to do with the surroundings of people and society, whether today or in the future. Here, on the other hand, the word ‘ecological’ is used, meaning the conservation of nature according to the logic of nature as a legal subject,” he says.

For Ezio Costa, executive director of FIMA and an academic at the University of Chile Law School, “ecology is about how human activities harmonize with nature, and if we want to preserve natural systems, we have to be aware of that.”

AN ECOLOGICAL STATE

Irarrázabal points out that Article 1 of the proposed new constitution has a “completely etatist conception.” In this sense, he points out that the Magna Carta would focus on the state and not on people.

This, he says, means that all ecological measures and environmental protection are “solely in the hands of the state.” In his opinion, “environmental protection requires a public-private approach that has to do with environmental management and not with the prohibitive logic associated with the rights of nature.”

For Costa, recognizing the state as an ecological state means that its actions should prioritize “balancing our activities with nature” through all of its institutions, not just those with a more environmental mission. However, he says that “the ways through which the state will become a green state” and how this is put into practice will depend on the other chapters of the text.

Silvia Bertazzo, an academic at the Law School of the Universidad de los Andes, agrees that this concept must be “justified” in other norms of the constitutional text and in legal norms, since “the wording of the article is very general.” However, she points out that it is a matter of recognizing the value of the environmental issue and its priority for the formulation of future public policies.

On the other hand, Irarrázabal asserts that “an articulation is needed between nature as a subject of rights and the rights of people and social or economic rights.” In this sense, the UC proposed the principle of sustainability as a framework for resolving conflicts between constitutional guarantees, an initiative that was not accepted by the Commission, according to the scholar.

The former undersecretary points out that this could lead to problems of interpretation and legal uncertainty and have a negative impact on environmental protection. “If you add to that the problems with property rights, water rights and mining rights, it could lead to a lack of investment and maintenance of infrastructure, which in turn could lead to a deterioration of environmental protection,” he says.

Another issue that has arisen since the enshrinement of the rights of nature, and which is gaining renewed importance with the enshrinement of the ecological state, is the relationship between the economic model and environmental protection. Some “environmentalists” have pointed out that the new vision being proposed represents an incompatibility between the two.

However, Costa does not believe “that the ecological state is incompatible with any economic model, but rather with the practices of all models that involve excessive destruction of nature.” In this sense, he adds that there are certain activities that, if not carried out in accordance with the norms, cause damage that “must be avoided and limited.” For this reason, he believes that the right model for this new vision “is still under construction at the global level.”

Bertazzo notes that “if the ecological state is understood as one that aims at extreme conservation of resources, this clearly clashes with the economic model.” On the other hand, she points out that a vision from the perspective of sustainable development “would not be incompatible with a limited use of the environment.”

To protect the environment, Costa and other scholars have proposed the creation of a constitutionally autonomous Ombudsman for Nature. The goal of this body would be to defend the rights of nature and perform other duties, such as hearing state lawsuits for environmental damage, which are currently being considered by the State Defense Council.

According to Costa, this would be a “counterweight to state power for the protection of nature, its rights, and environmental human rights, since governments are often tempted in the short term to exploit the environment intensively, which can be harmful to future generations.”

INTERNATIONAL EXPERIENCE

Chile will be the first country in the world to define itself as an ecological state, because although this term appears in other constitutional texts, it is not used as a concept for the state. However, in recent years there has been a growing trend to incorporate environmental protection at the constitutional level. In the region, Colombia, Ecuador and Bolivia are the countries that have enshrined important protection of nature in their constitutions.

The Ecuadorian constitution is considered an “ecological” constitution. In fact, it is the only one in the world that recognizes the rights of nature to this day. Mario Melo points out that “the constitutional recognition of the legal personality of nature or the pachamama represents a watershed in the history of contemporary constitutional law, not only in terms of the protection of nature and the environment, but also in terms of legal subjects.

Article 14 of the Constitution “recognizes the right of the people to live in a healthy and ecologically balanced environment that ensures sustainability and a good life, “su makawsay.” Article 15 also states that “the State shall promote in the public and private sectors the use of environmentally friendly technologies and environmentally friendly and sustainable alternative energies.”

Bolivia enshrines that “people have the right to a healthy, protected and balanced environment. In this sense, Article 299, second paragraph, states that the State and autonomous territorial entities must “protect, preserve and contribute to the protection of the environment and wildlife, maintain the ecological balance and control pollution.”

“What we see in the Convention could be called an Andean constitutionalism that takes Ecuador and Bolivia as a reference point, and if you analyze the ranking of environmental performance, both countries are in a pretty bad position,” Irarrázabal says. He explains that the most developed countries protect the environment the best, because “when economic growth is restricted, the protection of nature is compromised.”

On the other hand, Costa sees no similarity between the Chilean process and those of Ecuador and Bolivia. He argues that the initiative to protect the environment in the country comes from the people and not from the political apparatus, and that “if the constitution is approved, it will be the first to be implemented in such a declared climate emergency.”

WatchDog PAUTA is a joint project of the Faculty of Communication of the Universidad de los Andes and PAUTA for fact-checking. It seeks to put issues on the agenda and verify their truthfulness from a positive rather than an inquisitorial perspective.

With information from PAUTA