RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Beate Klarsfeld’s adventure in Paraguay to find Nazi doctor Josef Mengele is part of an exhibition of photos by Frenchman Alain Keler, who accompanied the famous war criminal hunter on an unsuccessful mission, but whose result was the portrait of a country subjected to Alfredo Stroessner’s dictatorship.

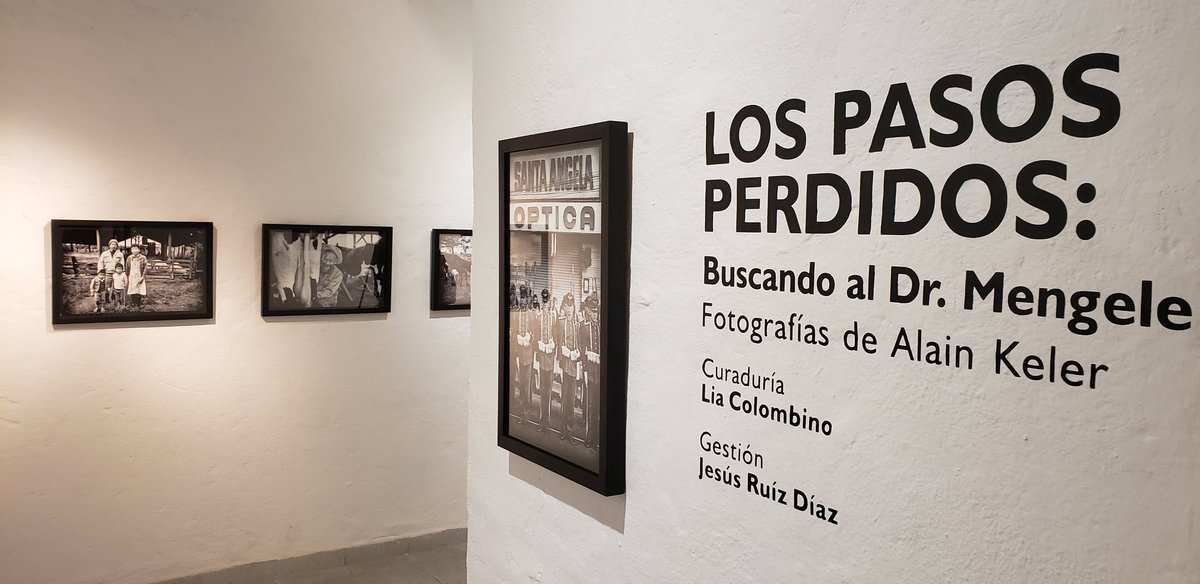

Hence the title of the exhibition that opened this week at the Museo del Barro in Asuncion: “The lost steps”, since Klarsfeld did not find those of the “angel of death” of the Auschwitz extermination camp, who had died years before the Nazi hunter arrived in the South American country.

Read also: Check out our coverage on Paraguay

Klarsfeld did not know of his death in her third visit to Asuncion, in May 1985, when she arrived with Serge, her husband, and Keler, who was going to capture with his objective the tracing of Mengele (1911-1979).

The first actions of Klarsfeld were to demonstrate in front of the Palace of Justice with a banner in which she denounced the asylum granted Mengele by Stroessner, also of German origin and strong man of the longest dictatorship of the Southern Cone (1954-1989).

“Stroessner, you lie when you say you don’t know where Mengele is” is the sign carried by Klarsfeld (1939) and one of the photos of the German Nazi hunter recorded by Keler’s camera (1945).

Despite this attitude of denunciation, Klarsfeld’s objective was to find Mengele, with the conviction that the Nazi doctor was hiding in the south of Paraguay, in the ranch of one of the German colonists who had emigrated to that part of the country, and with Stroessner’s support.

“Mengele was sought in Paraguay because they had news that it was the last place where he had been seen. There were photos supposedly taken in Paraguay. She had news that the Stroessner regime had hidden Nazis with other identities,” Lia Colombino, the curator of the exhibition, told Efe.

Klarsfeld and Keler’s “steps” led them to Hotel Tirol, in the southern city of Encarnación, where Mengele, responsible for selecting which new Auschwitz prisoners would die in the gas chambers and which would be enslaved or subjects of his “scientific” experiments, was believed to have stayed.

Mengele’s stay in Paraguay and in neighboring Argentina, where he took refuge in 1949 is documented by several authors, although it was in Brazil where he met his end.

Mengele had died in 1979, drowned on a Brazilian beach after suffering a cerebral hemorrhage while using the identity of Wolfgang Gerhard, although this was not revealed until after Klarsfeld’s visit.

The fact was not accepted either by the Government of Israel or by Klarsfeld, who was preceded by a whole campaign of discovery and denunciation of Nazis, both in Europe and South America, where she pushed for Bolivia to extradite Klaus Barbie to France.

Colombino recalls that it was not until 1992 when the doubts were cleared up after the DNA test carried out after the visit to Brazil of Mengele’s son, who in the past had thought his father was his uncle.

STROESSNER’S PARAGUAY

Despite this outcome, the work of Klarsfeld and Keler’s camera shows a country imprisoned by a dictatorship that had lasted for a long time thanks to the support of the United States.

The dictator himself appears in one of the photos in a march in homage to the veterans of the Chaco War between Paraguay and Bolivia (1932-1935).

Within a series of prints of military, police, and an atmosphere of backwardness and poverty that, according to Colombino, go beyond mere photojournalism.

“He was a photojournalist, but the photos go beyond photojournalism, in addition to that, there is an aesthetic vision, which tells its own truth. There is something that the composition itself is showing us beyond the document,” said the curator.

“Every image that reveals to us this recent past, which is not paper-mâché, helps in the construction of a memory,” she added.

Colombino expounds on that argument in one of the exhibition texts, whose full title is “The lost steps: searching for Dr. Mengele.”

“These photographs are lost steps that are now recovered to form part of the memory of our recent past, that past that still does not go away.”