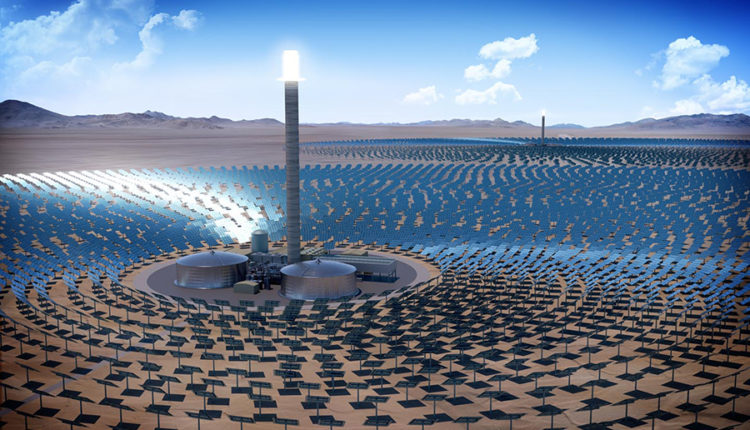

RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Nearly 10,600 heliostats (mirrors), 392,000 solar panels, and a tower 250 meters high. These are the colossal dimensions of Cerro Dominador, the first concentrated solar power plant in Latin America, inaugurated this Tuesday in the north of Chile, in the middle of the Atacama Desert.

Covering 1,000 hectares and located in an area with one of the highest levels of solar radiation in the world, 100 kilometers from the northern city of Calama, the project consists of two components: a 100 MW photovoltaic system, in operation since 2017, and an innovative solar thermal system, with 110 MW of installed capacity, a pioneer in the region and inaugurated this day.

Together, both components will generate a total capacity of 210 megawatts and will supply green energy to the Chilean power grid.

“It is a plant that is at the frontier of knowledge and technology. No plant has better technology than this one,” Chilean President Sebastián Piñera said during the inauguration.

The project will help avoid the emission of 630,000 tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) per year, which is equivalent to the circulation of 135,000 vehicles per year, “more than the number of cars in this region Antofagasta”, added the president.

With a total investment of 1.3 billion dollars, the complex is financed by the European Union and the German Development Bank KfW. Its main builders are the Spanish companies Acciona and Abengoa.

The Cerro Dominador solar plant is owned by a company of the same name, belonging to the U.S. investment fund firm EIG Global Energy.

THE SECOND TALLEST TOWER IN CHILE

One of the star elements of the project is the 250-meter central tower where the heat receiver is located and to which the thousands of heliostats will be pointed.

It is the second tallest building in Chile, only surpassed by the 300-meter skyscraper in Santiago known as the Costanera Center, one of the tallest on the continent.

The heliostats are mirrors of 140 square meters of reflecting surface and 3 tons of weight each, which follow the sun’s trajectory with movement on two axes, reflecting and directing the solar radiation towards the receiver.

Through this receiver, molten salts circulate at a temperature of 560 degrees Celsius, transferring the heat to a circuit that drives a steam turbine to generate electricity.

“The molten salts can be stored for up to 17.5 hours, which allows the system to continue operating even without direct sunlight, and there is reliable electricity production 24 hours a day,” explained the project’s CEO, Fernando Gonzalez.

Chile, a country of 19 million inhabitants and very extreme geography, with desert to the north and large forests to the south, can produce 70 times more electricity than it needs today.

“Chile was a poor country in the energies of the past; we had little oil, little coal, little gas, but immensely rich in the energies of the future”, said the president.

In the last six years, solar and wind energy share in the country’s energy matrix has increased tenfold. According to official data, renewable energies will reach 70% of it by 2030.

In 2021, Piñera said, more clean energy projects will be inaugurated in Chile “than in all the country’s previous history”, with an installed capacity of almost 6,700 MW.

“If we do not change course, we are heading towards an ecological disaster, the citizenship demands us, as a moral imperative, to change that course, and technology provides us with the tools to do so”, he concluded.

According to the organization’s announcement, the next COP26 climate summit, to be held in Glasgow (Scotland) next November, will strongly emphasize the importance of ending the world’s dependence on coal and the opportunities for renewable energy last May.

On the current trajectory of carbon dioxide emissions, the temperature is expected to rise between 3 and 5 degrees Celsius by the end of the century, according to the UN, which aims to limit warming to 1.5 °C.

The UN considers that this goal “is not impossible” but that it “would require unprecedented transitions in all aspects of society” and for which “the next ten years are critical”.