By Gustavo Sierra

RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL – Mafia law does not provide for voluntary retirement. The vast majority of capos, lieutenants and hitmen die very young. Those who remain, generally because they have spent many years in prison, may decide to step aside, but they will never be able to leave the organization.

What we are seeing now, in the case of the big drug traffickers, is that after serving long sentences, they are returning to rearm the cartels and try to occupy the place they had as big capos.

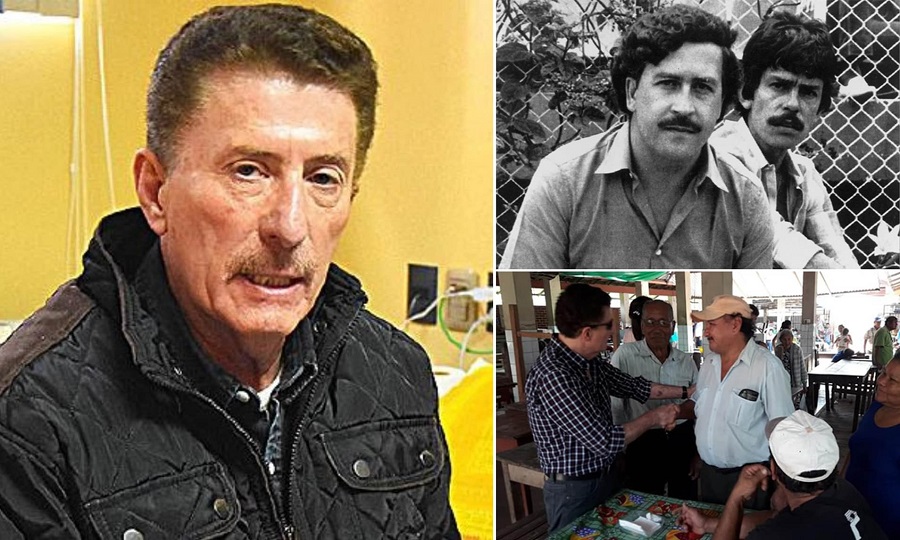

That is the case of Jorge Roca, better known as “Techo de Paja,” who was arrested in Lima on March 9th. It was during a joint operation with U.S., Colombian and Peruvian agents. Roca had reorganized his cartel and was dedicated to moving top-level cocaine from the “kitchens” of Santa Cruz de la Sierra to the United States, passing through Brazil, Venezuela and Mexico. In the old days, he became one of the major suppliers of the Medellín Cartel led by Pablo Escobar.

He was believed to be retired after spending 27 years in a high-security prison in California and several months in a Bolivian prison until he escaped while being treated in a private clinic in La Paz. He dropped off the police radar in 2019 and sent messages that he was no longer in the game. It wasn’t true.

“Straw Roof” is the nephew of Roberto Suarez Gomez, Bolivia’s “cocaine kingpin,” who became famous for offering to pay off his country’s foreign debt — at the time US$3 billion – in exchange for impunity. He began working for the organization from Los Angeles. He ran a typical used car business while behind the scenes he distributed the cocaine shipped to him by his uncle and the Los Pepes clan.

The money he laundered in California was invested in his native Beni. There he had several cattle ranches, an equestrian club, a supermarket chain and a huge mansion in Santa Cruz de la Sierra. At the same time, he was building another empire in the United States, with luxurious residences and the typical ostentatious cars of the narcos. He accumulated some US$70 million at the time.

On December 16th, 1990, Jorge Roca Suarez and his wife Cecilia were arrested after a DEA raid on their 19-room home in San Marino, California. He was hit with over than 30 charges of drug trafficking, money laundering, bank fraud, tax evasion and illegal export of monetary base. He was sentenced to 30 years in prison.

His sister, Beatriz Asunta “Chunty” Roca, and his wife were sentenced to 5 years in prison for money laundering. In an interview he gave to the Bolivian newspaper El Deber, “Techo de Paja” said that he had used those years to study and graduate as an attorney specializing in political and criminal law. In April 2018, he was granted early release and Suarez returned to Bolivia.

As soon as he got off the plane in La Paz he was again detained to serve an old 15-year prison sentence. Nine months later, Suarez was given a 10-day pass under police supervision to visit a clinic for an unspecified ailment. He escaped from the place on the night of December 8th, 2018. He disappeared until he was arrested last month in Lima.

“Roca’s case illustrates how some drug traffickers manage to revive their illegal businesses, despite having spent decades in prison,” wrote specialist organization InSight Crime in its analysis. And security consultant Arturo Arango assures that “it is very difficult to think of a retirement from the traditional point of view. Organized crime has control mechanisms over its own members, and when someone wants to leave, the rug is pulled out from under everyone else. Imagine the retirement of a capo who knows everything about everyone. Whoever succeeds him would try to kill him.”

According to the DEA, the U.S. agency that fights drug trafficking, there are increasing examples of old capos returning to their countries and trying to regain power in their organizations. An emblematic case is that of Rafael Caro Quintero, a mythical capo who in the 1970s was one of the founders of the Guadalajara Cartel.

His brother Miguel led another cartel, the Sonora cartel. He is considered the “capo of all capos.” He ordered the murder of DEA agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena and writer John Clay Walker. The FBI has a US$20 million reward for his head. In 1985 he was captured in Costa Rica and was held in several Mexican prisons until his release in 2013. Since then he is believed to be in the Sinaloa mountains under the security of the cartel led by “El Chapo” Guzman and “El Mayo” Zambada. A journalist interviewed him at a house in Mazatlan where he allegedly lived for some time in 2018.

In the Mexican narco world he is revered and respected. He continues to receive dividends from the sale of cocaine from several capos who consult him permanently.

In 2011, Victor Patiño Fomeque, a.k.a. “the beast” or “the chemist,” was at the heart of a war between the Urabeños and the Rastrojos for control of the Cali Cartel’s assets. According to information published by El Tiempo, Patiño Fómeque allegedly played the role of mediator between the Beltrán Leyva Cartel in Mexico and the Urabeños in exchange for the latter’s support in their war against the Rastrojos.

He did this after serving a 12-year sentence in the United States after becoming a DEA collaborator and snitching on several Colombian drug lords. All this while continuing to work for the interests of the powerful Norte del Valle cartel. After disputes between his former associates and enemies, he returned to the United States where he controls drug distribution in several states.

In other cases, the return of old capos revives old struggles. A wave of violence in the department of Valle del Cauca in 2015 was linked to the return of several old drug traffickers and front men. More recently, the return of drug trafficker and former paramilitary Hernan Giraldo in January this year generated the same reaction. His family, now converted into a criminal group known as “Los Pachenca,” still maintains control over drug trafficking on Colombia’s Caribbean coast, and his return has generated fear among communities in the region.

In Mexico, there were two known cases of drug bosses who retired and handed over command in exchange for protection. But they remained connected to the organization. They are the capos Juan N. Guerra, founder of the Gulf Cartel, and Miguel Angel Felix Gallardo, “El Jefe de Jefes” (The Boss of Bosses). Guerra ceded control of the organization to his nephew Juan Garcia Abrego, currently imprisoned in the United States.

Gallardo, who in the 1980s was the main leader of drug trafficking in the country, was arrested in 1989. In his book El Cartel, journalist Jesús Blancornelas tells how the former leader ordered the distribution of the territory he controlled among some of his collaborators. The beneficiaries later became cartel bosses, such as Amado Carrillo Fuentes, “The Lord of the Skies,” the Arellano Felix brothers or Joaquin Guzman Loera, “El Chapo”.

“Their retirement was possible because the scenario in which drug trafficking took place was different,” explains consultant Arturo Arango. “In many cases, cartel bosses were protected by or allied with police authorities. And it appears that this protection is still intact for Gallardo, who also continues to receive a share of the profits from the businesses of his former “employees.” Los Tigres del Norte sing the famous corrido created in his honor: “El jefe de jefes” (The boss of bosses). He was a character in several TV series, the last one “Narcos” by Netflix played by actor Diego Luna.

The case of Bolivian Jorge “Straw Roof” Roca becomes emblematic in this story of old traffickers not only because he continued to lead operations during his years in prison, but also because he returned to build a new South American criminal empire.

Oh, and in case you’ve been wondering since you started reading this article where Roca’s curious nickname came from, here’s the explanation: that ‘roof’ was a nickname his uncle, the ‘King of Cocaine,’ had for him. “When Jorge was a child,” a person related to the family told the newspaper El Deber, “Roberto began to call him ‘techito’ or ‘techo’ (roof), because when I played with him in a lagoon, during the time we lived in Santa Ana de Yacuma (Beni), the water did not wet his scalp and it would run off his wavy, shocky hair.

Source: Infobae